Summary

-

1.

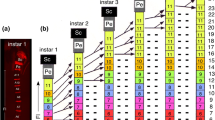

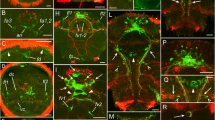

Temporal and spatial aspects of postembryonic optic lobe development in a Lepidopteran,Danaus plexippus plexippus L., were analyzed using serial section reconstructions and H3-thymidine radioautography to display loci of cell production and progressive movements of populations of cells.

-

2.

Optic lobe development begins early in larval life and is continuous without perceptible fluctuations corresponding to molting. The production of new cells begins during the first larval stages and is completed within a few days after pupation.

-

3.

Development of adult optic centers appears to be independent of the larval optic center and also of adult eye development which does not get underway until pupation. At pupation the larval stemmata migrate toward the brain along the stemmatal nerve which persists and later serves as the framework by which ommatidial neurones reach the brain.

-

4.

Ganglion cells of the adult optic lobe are produced by two coiled rod-like aggregates of neuroblasts, the inner and outer optic lobe anlagen, which lie lateral to the protocerebrum and are already present in the brain of the newly hatched larva. Neuroblasts of the anlagen divide both symetrically to produce more neuroblasts and asymmetrically to yield one neuroblast and one smaller cell, the ganglion-mother cell. Subsequent ganglion-mother cell divisions produce the new ganglion cells which are continuously displaced from the anlage by additional cells. Following pupation mitotic activity in the anlagen diminishes and neuroblasts degenerate. By the fourth day after pupation the anlagen have disappeared.

-

5.

Fiber differentiation begins within a few days of cell formation. Fibers travel in bundles usually toward the center of the coiled anlagen where they form the neuropile masses. With contributions from a growing population of ganglion cells, fibermasses grow rapidly in size and complexity.

-

6.

The geometric arrangement of anlagen, cortices, and neuropile is dynamic and interdependent. Progressive changes in anlagen configuration result from the combined effects of an increasing neuroblast population, growing optic cortices, and expanding fibermasses between the arms of the anlagen. In turn, the cortices and fibermasses which follow anlagen contours also change form. The complex of these parts, initially small and coiled, gradually enlarges and uncoils until at the time of anlagen degeneration the three optic fibermasses and their cortices are in approximately their final arrangement.

-

7.

The outer anlage forms cells of the lamina cortex at its lateral rim and cells of the medulla at its medial rim. Cells of the lobula cortex are produced by strands of inner anlage neuroblasts extending laterally between the arms of the coiled outer anlage.

-

8.

Cells of the medulla cortex are first seen during the second larval instar and several days later the medulla fibermass is discernible. Cortex and fibermass lie medial to the outer anlage which is moved progressively more laterally as more cells are produced. Cells labelled with H3-Td R at the beginning of the third instar become the tangential cells of the adult optic lobe. Those labelled at the fourth and fith stages occupy positions near the tangential cells, and those labelled at pupation ultimately lie at the lateral edge of the cortex.

-

9.

Production of the lamina cortex begins later and procedes more slowly. Cells here are first apparent during the fourth instar and form a cellular cap covering the lateral part of the optic lobe. Labelling studies show that the earliest formed cells finally occupy the most posterior region of the lamina cortex. The lamina fibermass is first seen in the mid-fifth instar brain.

-

10.

For most of larval life the lobula cortex forms a plug of cells just inside the lamina. While the anlage remains coiled, the first-formed cells are at the center of the plug, but ultimately they lie at the most medial part of the cortex. Production of lobula cells begins during the third instar and by the mid-fourth instar the lobula neuropile can be seen medial to them.

-

11.

As a result of these studies with H3-Td R injection and fixation after varying intervals it has been possible to estimate the age of cells at a particular developmental stage. Because this material offers an organized arrangement of cells of a wide range of identifiable ages and levels of maturation within a single individual, it provides an excellent model for the study of progressive neurone differentiation.

Zusammenfassung

-

1.

Zeitliche und räumliche Aspekte der postembryonalen Entwicklung des Sehlappens inDanaus plexippus plexippus L. sind mittels Rekonstruktion von Serialschnitten und3H-Thymidin-Markierung zur Darstellung von Zellteilungszentren und Zellmigration untersucht worden.

-

2.

Die Entwicklung des Sehlappens beginnt in frühen Larvenstadien und geht kontinuierlich vor sich, ohne Zyklen, die den Häutungen entsprechen würden. Die ersten neuen Zellen werden im ersten Larvenstadium produziert, und die Zellproduktion kommt einige Tage nach der Verpuppung zum Stillstand.

-

3.

Die Entwicklung der adulten Sehzentren vollzieht sich unabhängig vom larvalen Sehzentrum und auch unabhängig von der adulten Augenentwicklung, die erst bei der Verpuppung anfängt. Bei der Verpuppung wandern die larvalen Stemmata entlang dem Stemmatalnerven zum Gehirn; der Stemmatalnerv bleibt erhalten und dient später als Rahmen, in dem die Neuronen der Ommatidien das Gehirn erreichen.

-

4.

Ganglionzellen des adulten Sehlappens entstehen durch zwei gewundene, stabartige Aggregate von Neuroblasten, die inneren und äußeren Sehlappen-Anlagen, die lateral des Protocerebrums liegen und schon im Gehirn der frisch geschlüpften Larve vorhanden sind. Die Neuroblasten dieser Anlage teilen sich symmetrisch, wobei neue Neuroblasten erzeugt werden, aber auch asymmetrisch, wobei jeweils ein Neuroblast und eine kleinere Zelle gebildet wird; letztere ist eine Ganglion-Mutterzelle. Nachfolgende Teilungen der Ganglion-Mutterzellen produzieren neue Ganglionzellen, die kontinuierlich durch immer neue Zellen von der Anlage verdrängt werden. Nach der Verpuppung nimmt die mitotische Aktivität in den Anlagen ab und die Neuroblasten degenerieren. Am vierten Tage nach der Verpuppung sind die Anlagen verschwunden.

-

5.

Differenzierung der Fasern beginnt innerhalb weniger Tage nach der Zellbildung. Fasern erstrecken sich in Bündeln gewöhnlich in Richtung des Zentrums der gewundenen Anlagen, wo sie die Neuropilmassen bilden. Mit Beiträgen der wachsenden Population von Ganglionzellen wachsen die Fasermassen rasch und nehmen an Komplexität zu.

-

6.

Die geometrische Disposition der Anlage, Cortices und Neuropile ist dynamisch und abhängig voneinander. Progressive Änderungen in der Disposition der Anlagen sind das Resultat der kombinierten Wirkung einer zunehmenden Neuroblastenpopulation, wachsender Cortices, und sich ausdehnender Fasermassen zwischen den Armen der Anlagen. Gleichzeitig ändert sich auch die Form der Cortices und Fasermassen, die den Umrissen der Anlagen folgen. Der Komplex aller dieser Teile, anfänglich klein und gewunden, wird allmählich größer und entwunden bis schließlich, zum Zeitpunkt der Anlagen-Degeneration, die drei Fasermassen und ihre Cortices in einigermaßen endgültiger Position liegen.

-

7.

Die äußere Anlage bildet Zellen des Lamina-Cortex an ihrem seitlichen Rand, und Zellen der Medulla am medialen Rand. Zellen des Lobula-Cortex werden durch Stränge von Neuroblasten der inneren Anlage gebildet, die sich lateral zwischen die Arme der gewundenen äußeren Anlage erstrecken.

-

8.

Zellen des Medulla-Cortex sind zum ersten Mal im zweiten Larvenstadium sichtbar, und mehrere Tage später wird die Medulla-Fasermasse sichtbar. Cortex und Fasermasse liegen medial der äußeren Anlage, die immer mehr lateral zu liegen kommt dadurch, daß immer neue Zellen gebildet werden. Zellen, die am Anfang des dritten Larvenstadiums mit3H-Thymidin markiert werden, findet man als tangential zum Sehlappen liegend. Zellen, die während des vierten und fünften Stadiums markiert werden, kommen nahe bei den tangentialen Zellen zu liegen, und Zellen, die bei der Verpuppung markiert werden, liegen schließlich am seitlichen Rand des Cortex.

-

9.

Produktion des Lamina-Cortex beginnt später und verläuft langsamer. Hier werden Zellen zum ersten Mal während des vierten Stadiums sichtbar und bedecken den lateralen Teil des Sehlappens. Studien mit markierten Zellen zeigen, daß die zuerst gebildeten Zellen schlußendlich in der am meisten posterior gelegenen Region des Lamina-Cortex zu liegen kommen. Die Lamina Fasermasse wird zum ersten Mal im Hirn des mittleren fünften Stadiums sichtbar.

-

10.

Während des größten Teils der Larvalzeit bildet der Lobula-Cortex einen Zellpfropf direkt innerhalb der Lamina. Während die Anlage gewunden ist, liegen die erstgebildeten Zellen im Zentrum des Pfropfens, aber schließlich liegen sie im mediansten Teil des Cortex. Produktion der Lobulazellen beginnt während des dritten Stadiums, und im mittleren vierten Stadium kann man medial der Lobulazellen bereits die Lobula-Neuropile sehen.

-

11.

Durch die autoradiographischen Markierungsexperimente wurde es möglich, das Alter von Zellen in einem bestimmten Entwicklungsstadium zu schätzen. Weil dieses Material eine organisierte Anordnung von Zellen verschiedenen Alters und verschiedenen Reifungsalters darstellt innerhalb eines einzigen Organismus, dürfte es sich als ausgezeichnetes Modell für das Studium progressiver Differenzierung von Neuronen erweisen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literature

Bauer, V.: Zur Innern Metamorphose des Centralnervensystems der Insecten. Zool. Jb., Abt. Anat. u. Ontog.20, 123–152 (1904).

Bott, H. R.: Beiträge zur Kenntnis vonGyrinus natator substriatus. Steph. Z. Morph. Ökol. Tiere10, 252–306 (1928).

El Shatoury, H. H.: Differentiation and metamorphosis of the imaginal optic glomeruli ofDrosophila. J. Embryol. exp. Morph.4, 240–247 (1956).

Grabenhorst, A.: Die mit der Ausbildung des Frontauges zusammenhängenden postembryonalen Entwicklungsvorgänge im Lobus opticus einiger Ephemeridenmännchen. Z. Morph. Ökol. Tiere18, 430–473 (1930).

Hanström, B.: Comparison between the brains of the newly hatched larva and the imago ofPieris brassicae. Ent. Tidsskr.46, 43–52 (1925).

Hertweck, H.: Anatomie und Variabilität des Nervensystems und der Sinnesorgane vonDrosophila melangaster (Meigen). Z. wiss. Zool.139, 559–663 (1931).

Johansen, H.: Die Entwicklung des Imagoauges vonVanessa urticae L. Zool. Jb., Abt. Anat. u. Ontog.6, 445–480 (1892).

Madhavan, N. K.: Occurrence of anucleolate oöcytes inChrysocaris purpureus (Westw.) Exp. Cell Res.30, 431–432 (1963).

Nordlander, R., andJ. S. Edwards: Morphological cell death in the postembryonic development of the insect optic lobes. Nature (Lond.)278, 780–781 (1968a).

—: Morphology of the larval and adult brains of the monarch butterfly,Danaus plexippus plexippus L. J. Morph.126, 67–94 (1968b).

—: Postembryonic brain development in the monarch butterfly,Danaus plexippus plexippus L I. Cellular events during brain morphogenesis. Wilhelm Roux' Arch.162, 197–217 (1969).

Panov, A.: The structure of the insect brain during successive stages of postembryonic development. III. Optic lobes. Ent. Obozrenie (trans.)39, 55–58 (1960).

Pflugfelder, O.: Die Entwicklung der Optischen Ganglien vonCulex pipiens. Zool. Anz.117, 31–36 (1937).

Pyle, R.: Changes in the nervous system of Lepidoptera during metamorphosis. Thesis, Harvard University (1941).

Schrader, K.: Untersuchungen über die Normalentwicklung des Gehirns und Gehirntransplantationen bei der MehlmotteEphestia kuhniella Zeller nebst einigen Bemerkungen über das Corpus Allatum. Biol. Zbl.58, 52–90 (1938).

Umbach, W.: Entwicklung und Bau des Komplexauges der Mehlmotte,Ephestia kuhniella Zeller, nebst einigen Bemerkungen über die Entstehung der optischen Ganglien. Z. Morph. Ökol. Tiere28, 561–594 (1934).

Viallanes, H.: Le ganglion optique de quelques larves de Diptéres (Musca, Eristalis, Stratiomys). Ann. Sci. nat. Zool.19, 1–34 (1885).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nordlander, R.H., Edwards, J.S. Postembryonic brain development in the monarch butterfly,Danaus plexippus plexippus L.. W. Roux' Archiv f. Entwicklungsmechanik 163, 197–220 (1969). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00573531

Received:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00573531