Abstract

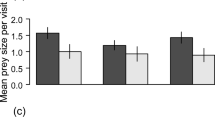

Adult magpies Pica pica provide parasitic great spotted cuckoo Clamator glandarius nestlings with a diet very similar to that fed to their own chicks. In both naturally and experimentally parasitized nests, great spotted cuckoo chicks were fed at a higher rate than magpie chicks in the same nest. This preferential allocation of food by magpie parents to great spotted cuckoo chicks is consistent with the supernormal stimulus hypothesis, because this result implies that cuckoo chicks provide stronger stimuli for parental care than host chicks. Great spotted cuckoo chicks receive most of the food brought to the nest by the foster parents, because they exploit a series of stimuli which jointly (or sometimes individually) operate as a supernormal stimulus. This hypothesis predicts that if any stimulus is masked, the efficiency of the cuckoo in eliciting parental care will decrease. Here, we analyze experimentally the effects of two of these stimuli, preferential feeding of large nestlings and of nestlings with conspicuous palatal papillae. Firstly, when we experimentally introduced one medium-sized (7–9 days) cuckoo chick into an unparasitized magpie nest where the largest magpie chick was 12–15 days old, the cuckoo did not receive significantly more food than the average or the largest magpie chick. Secondly, when unparasitized nests were experimentally parasitized with a cuckoo chick that had its gape painted to mimic that of magpie chicks, the parasitic cuckoo received less food than the average magpie chick.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bengtsson H, Rydén O (1981) Development of parent-young interaction in asynchronously hatched broods of altricial birds. Z Tierpsychol 56:255–272.

Birkhead TR (1991) The magpies. Poyser, London.

Brooke M de L, Davies NB (1989) Provisioning of nestling cuckoos Cuculus canorus by reed warbler Acrocephalus scirpaceus hosts. Ibis 131:250–256.

Buitron D (1988) Female and male specialization in parental care and its consequences in black-billed magpies. Condor 90:29–39.

Cramp S (ed) (1985) The birds of the Western Palearctic. vol IV. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Davies NB, Brooke M de L (1988) Cuckoos versus reed warblers: adaptations and counteradaptations. Anim Behav 36:262–284.

Dawkins R, Krebs JR (1979) Arms races between and within species. Proc R See Lond B 205:489–511.

Di Carlo EA (1971) Appunti sulla biologia del cuculo dal ciuffo (Clamator glandarius). Rivista Ital Ornitol 41:86–107.

Fry CH, Keith S, Urban EK (1988) the birds of Africa, vol III. Academic Press, London.

Gill BJ (1982) The grey warbler's care of nestlings: a comparison between unparasitized broods and those comprising a shining bronze-cuckoo. Emu 82:177–181.

Godfray HCJ (1991) Signalling of need by offspring to their parents. Nature 352:328–330.

Hussell DJ (1991) Regulation of food provisioning in broods of altricial birds. Acta Congr Internat Ornithol 20:946–960.

Johnson EJ, Best LB, Heagy PA (1980) Food sampling biases associated with the “ligature method”. Condor 82:186–192.

Kluijver HN (1933) Bijdrage tot de biologic en de ecologic van den spreeuw (Sturnus vulgaris L.) gedurende zijn voortplantingstijd. Versl Meded Plantenziekt Wageningen 69:1–145.

Lack D (1968) Ecological adaptations for breeding in birds. Chapman and Hall, London.

Lockie JD (1955) The breeding and feeding of jakdaws and rooks with notes on carrion crows and other Corvidae. Ibis 97:341–369.

Löhrl H (1968) Das Nesthäkchen als biologisches Problem. J Ornithol 109:383–395.

Martinez JG, Soler M, Soler JJ, Paracuellos M, Sanchez J (1992) Alimentación de los pollos de urraca (Pica pica) en relación con la edad y disponibilidad de presas. Ardeola 39:35–48.

Mason P (1986) Brood parasitism in a host generalist, the shiny cowbird. I. The quality of different species as hosts. Auk 103:52–60.

Mundy PJ (1973) Vocal mimicry of their hosts by nestlings of the great spotted cuckoo and striped crested cuckoo. Ibis 115: 601–604.

Mundy PJ, Cook AW (1977) Observations on the breeding of the pied crow and great spotted cuckoo in northern Nigeria. Ostrich 48:72–84.

Nur N (1984) The consequences of brood size for breeding blue tits. 2. Nestling weight, offspring survival and optimal brood size. J Anim Ecol 53:497–517.

Redondo T, Arias de Reyna L (1988) Vocal mimicry of hosts by great spotted cuckoo Clamator glandarius: further evidences. Ibis 130:540–544.

Rothstein SI (1990) A model system for coevolution: avian brood parasitism. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 21:481–508.

Royama T (1966) Factors governing feeding rate, food requirement and brood size of nestling great tits (Parus major). Ibis 108:313–347.

Rydén O, Bengtsson H (1980) Differential begging and locomotory behaviour by early and late hatched nestlings affecting the distribution of food in asynchronously hatched broods of altricial birds. Z Tierpsychol 53:209–224.

Soler M (1990) Relationships between the great spotted cuckoo Clamator glandarius and its corvid hosts in a recently colonized area. Ornis Scand 21:212–223.

Soler M, Soler JJ (1991) Growth and development of the great spotted cuckoos and their magpie host. Condor 93:49–54.

Soler M, Soler JJ, Martinez JG (in press a) Sympatry and coevolution between the great spotted cuckoo (Clamator glandarius) and its magpie (Pica pica) host. In: Rothstein SI, Robinson S (eds) Parasitic Birds and their hosts. Oxford Univ. Press.

Soler M, Soler JJ, Martinez JG, Møller AP (in press b) Chick recognition and acceptance:A weakness in magpies exploited by the parasitic great spotted cuckoo. Behav Ecol Sociobiol.

Tinbergen N (1951) The study of instinct. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Trivers RL (1974) Parent-offspring conflict. Am Zool 14:177–192.

Valverde JA (1953) Contribution à la biologic du coucou-geai, Clamator glandarius L. I. Notes sur le coucou-geai en Castille. Oiseaux 23:288–296.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Communicated by M.A. Elgar

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Soler, M., Martinez, J.G., Soler, J.J. et al. Preferential allocation of food by magpies Pica pica to great spotted cuckoo Clamator glandarius chicks. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 37, 7–13 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00173893

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00173893