Abstract

We investigate the electronic structure of a complex conventional superconductor, ZrB12 employing high resolution photoemission spectroscopy and ab initio band structure calculations. The experimental valence band spectra could be described reasonably well within the local density approximation. Energy bands close to the Fermi level possess t2g symmetry and the Fermi level is found to be in the proximity of quantum fluctuation regime. The spectral lineshape in the high resolution spectra is complex exhibiting signature of a deviation from Fermi liquid behavior. A dip at the Fermi level emerges above the superconducting transition temperature that gradually grows with the decrease in temperature. The spectral simulation of the dip and spectral lineshape based on a phenomenological self energy suggests finite electron pair lifetime and a pseudogap above the superconducting transition temperature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The relationship between pseudogap phase and superconductivity in high temperature superconductors is an issue of discussion for many years now1,2,3. While one school believes that the pseudogap arises due to some hidden order and/or effects not associated to superconductivity, the other school attributes pseudogap to the electron pair formation above the transition temperature, Tc as a precursor to the superconducting gap that leads to superconductivity upon establishment of the coherence among the electron pairs at Tc. Independent of these differences, it is realized that electron correlation plays a significant role in the occurrence of pseudogap phase in these unconventional superconductors4,5. Several questions are being asked on whether the pseudogap phase is specific to unconventional superconductors, electron correlation or low dimensionality is a necessity for such phase etc.

Apart from these issues, the quest of new superconducting compounds resulted into the discovery of superconductivity in cubic hexane, MB6 and dodecaborides, MB12 (M = Sc. Y, Zr, La, Lu, Th) those attracted much attention due to their interesting electronic properties6. ZrB12 is one such compound exhibiting relatively high superconducting transition temperature of 6 K in the MB12 family6. It forms in cubic structure as shown in Fig. 1. In Fig. 1(a), the real lattice positions are shown with the correct bond lengths and atom positions. Although, the structure appears to be complex, it is essentially a rock salt structure constituted by two interpenetrated fcc lattices formed by Zr and B12 units as demonstrated in Fig. 1(b) by compressing the B12 units for clarity. Various transport and magnetic measurements suggest a Bardeen-Cooper-Schriefer (BCS) type superconductivity in this material, which is termed as conventional superconductivity. Since, Zr atoms are located within the huge octahedral void space formed by the B12 units, the superconductivity in these materials could conveniently be explained by the electron-phonon coupling mediated phenomena involving primarily low energy phonon modes associated with the vibration of Zr atoms7.

The electronic properties of ZrB12 manifest plethora of conflicts involving the mechanism of the transition. For example, there are conflicts on whether it is a type I or type II superconductor8, whether it possesses single gap9 or multiple gaps10, etc. Interestingly, Gasparov et al.10 found that superfluid density of ZrB12 exhibits unconventional temperature dependence with pronounced shoulder at T/Tc ~ 0.65. In addition, they find different superconducting gap and transition temperatures for different energy bands and the values of the order parameter obtained for p and d bands are 2.81 and 6.44, respectively. Detailed magnetic measurements reveal signature of Meissner, mixed and intermediate states at different temperatures and magnetic fields11. Some of these variances were attributed to surface-bulk differences in the electronic structure12, the superconductivity at the sample surface13,14,15 etc. Evidently, the properties of ZrB12 is complex despite exhibiting signatures of BCS type superconductivity. Here, we probed the evolution of the electronic structure of ZrB12 employing high resolution photoelectron spectroscopy. The experimental results exhibit spectral evolution anomalous to conventional type superconductor and signature of pseudogap prior to the onset of superconductivity.

Results

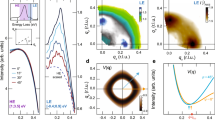

Valence band spectra obtained using He ii and Al Kα excitation energies are shown in Fig. 2(a) exhibiting three distinct features marked by A, B and C beyond 2 eV binding energies. The intensities between 6–10 eV binding energies represented by B are prominent in the He ii spectrum, while the relative intensity between 3–4 eV binding energies represented by A is enhanced in the x-ray photoemission (XP) spectrum. Such change in intensity in the angle integrated spectra may be attributed to the matrix elements associated to different constituent states forming the eigenstates of the valence band, which is a sensitive function of the photon energy16. Therefore, the photoemission cross section will vary with the photon energy that can be used to identify the orbital character of the energy bands. Considering this feature of the technique, the spectral feature, B can be attributed to dominant B 2p orbital character and the feature A to Zr 4d orbital character.

(a) XP and He ii valence band spectra of ZrB12.

The lines show the simulated XP spectrum from the band structure results. Calculated partial density of states of (b) Zr 4d t2g (dashed line), 4d eg (thin solid line) & 5s (thick solid line) and (c) B 2s (solid line) and 2p (dashed line) partial density of states.

Energy band structure of ZrB12 has been calculated within the local density approximations (LDA). The calculated partial density of states (PDOS) corresponding to Zr 4d & 5s and B 2s & 2p states are shown in Fig. 2(b) and 2(c), respectively. Zr 5s contribution appears in the energy range of 5–7.5 eV above the Fermi level with negligible contributions in the energy window studied here as shown by thick solid line in Fig. 2(b). B 2s contributions appear beyond 6 eV binding energies. Dominant contribution from B 2p PDOS appears between 1.5 to 10 eV binding energies. The center of mass of the B 2p PDOS (considering both occupied and unoccupied parts) appears around 1.9 eV binding energy. The center of mass of the entire Zr 4d PDOS appear around 2.8 eV above  , which is about 4.7 eV above the center of mass of the B 2p PDOS. Thus, an estimate of the charge transfer energy could be about 4.7 eV in this system. The ground state is metallic with flat density of states across

, which is about 4.7 eV above the center of mass of the B 2p PDOS. Thus, an estimate of the charge transfer energy could be about 4.7 eV in this system. The ground state is metallic with flat density of states across  arising due to highly dispersive energy bands in this energy range. The density of states at

arising due to highly dispersive energy bands in this energy range. The density of states at  possess close to 2:1 intensity ratio of the B 2p and Zr 4d orbital character.

possess close to 2:1 intensity ratio of the B 2p and Zr 4d orbital character.

The electronic states with t2g and eg symmetries, shown in Fig. 2(b), exhibit almost overlapping center of mass suggesting negligible crystal field splitting (crystal field splitting ~ 100 meV). The energy bands are shown in Fig. 3. eg bands are relatively narrow and exhibit a gap at  . The intensity at

. The intensity at  essentially have highly dispersive t2g symmetry.

essentially have highly dispersive t2g symmetry.

Using the above band structure results, we calculated the XP spectrum considering the photoemission cross section of the constituent partial density of states as discussed later in the Method section. The calculated spectrum shown by solid line in Fig. 2(a) exhibits an excellent representation of the experimental XP spectrum. It is clear that the feature, C in the energy range 10–14 eV corresponds to photoemission signal from B 2s levels. The features, A and B arise due to hybridized B 2p - Zr 4d states. The relative contribution from Zr 4d states is higher for the feature A.

In order to probe the electron correlation induced effect on the electronic structure, we have carried out electron density of states calculation using finite electron correlation among the Zr 4d electrons, Udd as well as that among B 2p electrons, Upp. In Figs. 4(a) and 4(b), we show the calculated results for Zr 4d and B 2p PDOS with Udd = 0 (solid line) and 6 eV (dashed line) for the Zr 4d electrons. Even the large value of Udd of 6 eV does not have significant influence on the occupied part of the electronic structure, while an energy shift is observed in the unoccupied part. Such scenario is not unusual considering the large radial extension of 4d orbitals and poor occupancy17. The inclusion of an electron correlation, Upp of upto 4 eV for B 2p states exhibits insignificant change in the results. Considering Zr being a heavy element, we carried out similar calculations including spin-orbit interactions and did not find significant modification in the results - we have not shown these later results to maintain clarity in the figure. All these theoretical results suggest that consideration of electron correlation within the LSDA + U method has insignificant influence in the occupied part of the electronic structure of this system.

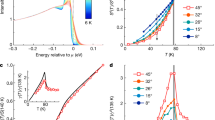

We now investigate the spectral changes near  with high energy resolution in Fig. 5. The spectral density of states (SDOS) are calculated by symmetrizing the experimental spectra;

with high energy resolution in Fig. 5. The spectral density of states (SDOS) are calculated by symmetrizing the experimental spectra;  and shown in Figs. 5(c) and 5(d). Such an estimation of SDOS is sensitive to the definition of the Fermi level, which is carefully derived at each temperature by the Fermi cutoff in the valence band spectra for silver mounted on the sample holder in electrical connection with the sample and measured using identical experimental conditions. The other effect is the asymmetry across the Fermi level. This can be addressed by obtaining the SDOS by the division of the resolution broadened Fermi-Dirac distribution function. The results are shown in Figs. 5(e) and 5(f) for He ii and He i spectra, respectively. Clearly, the SDOS obtained following the later procedure exhibits symmetric SDOS across

and shown in Figs. 5(c) and 5(d). Such an estimation of SDOS is sensitive to the definition of the Fermi level, which is carefully derived at each temperature by the Fermi cutoff in the valence band spectra for silver mounted on the sample holder in electrical connection with the sample and measured using identical experimental conditions. The other effect is the asymmetry across the Fermi level. This can be addressed by obtaining the SDOS by the division of the resolution broadened Fermi-Dirac distribution function. The results are shown in Figs. 5(e) and 5(f) for He ii and He i spectra, respectively. Clearly, the SDOS obtained following the later procedure exhibits symmetric SDOS across  . The 30 K and 10 K data exhibit large noise above

. The 30 K and 10 K data exhibit large noise above  due to the division of negligibly small intensities by small numbers arising from Fermi-Dirac function at these temperatures. These results demonstrate the reliability of SDOS extraction procedures and also indicate signature of particle-hole symmetry in this system.

due to the division of negligibly small intensities by small numbers arising from Fermi-Dirac function at these temperatures. These results demonstrate the reliability of SDOS extraction procedures and also indicate signature of particle-hole symmetry in this system.

The spectral lineshape near the Fermi level often provides important information about the thermodynamic properties of the systems. For example, a lineshape dependence of  corresponds to Fermi liquid behavior18,19 - absence of linearity of SDOS with

corresponds to Fermi liquid behavior18,19 - absence of linearity of SDOS with  shown in Fig. 6(a) indicates a deviation from such a behavior in the present case. The decrease in intensity at

shown in Fig. 6(a) indicates a deviation from such a behavior in the present case. The decrease in intensity at  with the decrease in temperature may arise due to the disorder induced localization of the electronic states. Altshuler & Aronov showed that the charge disorder in a correlated system leads to

with the decrease in temperature may arise due to the disorder induced localization of the electronic states. Altshuler & Aronov showed that the charge disorder in a correlated system leads to  dependence of the density of states near Fermi level20, which has been proved employing photoemission spectroscopy21,22. In the present case, a plot of SDOS with

dependence of the density of states near Fermi level20, which has been proved employing photoemission spectroscopy21,22. In the present case, a plot of SDOS with  shown in Fig. 6(b) exhibits deviation from linearity.

shown in Fig. 6(b) exhibits deviation from linearity.

Interestingly, the curvatures at the exponents of 0.5 and 2 are opposite indicating an intermediate exponent for the present system. The simulation of SDOS as a function of  with α ≈ 0.9 exhibits linear dependence with energy for all the temperatures studied (see Fig. 6(c)). Such a behavior in a conventional superconductor is curious. Most interestingly, in Fig. 6(c), all the data below 150 K superimpose exactly and correspond to the same energy scale, while the data at 300 K exhibit similar energy dependence with a different slope. These results suggest signature of an incipient phase transition at an intermediate temperature.

with α ≈ 0.9 exhibits linear dependence with energy for all the temperatures studied (see Fig. 6(c)). Such a behavior in a conventional superconductor is curious. Most interestingly, in Fig. 6(c), all the data below 150 K superimpose exactly and correspond to the same energy scale, while the data at 300 K exhibit similar energy dependence with a different slope. These results suggest signature of an incipient phase transition at an intermediate temperature.

The SDOS at  is intense and flat at 300 K with large dispersion of the bands and correspond to a good metallic phase consistent with the band structure results. The decrease in temperature introduces a dip at

is intense and flat at 300 K with large dispersion of the bands and correspond to a good metallic phase consistent with the band structure results. The decrease in temperature introduces a dip at  . The dip gradually becomes more prominent with the decrease in temperature. The same scenario is observed in both, He i and He ii spectra indicating this behavior to be independent of the photon energy used. This dip may be attributed to a pseudogap appearing at low temperatures23. Although the probed lowest temperature is slightly above Tc, the dip grows monotonically with the decrease in temperature - a large suppression of the spectral weight at the Fermi level is observed at 10 K indicating relation of this dip to the superconducting gap. In order to estimate the energy gap in these spectral functions, we used a phenomenological self-energy,

. The dip gradually becomes more prominent with the decrease in temperature. The same scenario is observed in both, He i and He ii spectra indicating this behavior to be independent of the photon energy used. This dip may be attributed to a pseudogap appearing at low temperatures23. Although the probed lowest temperature is slightly above Tc, the dip grows monotonically with the decrease in temperature - a large suppression of the spectral weight at the Fermi level is observed at 10 K indicating relation of this dip to the superconducting gap. In order to estimate the energy gap in these spectral functions, we used a phenomenological self-energy,  following the literature24.

following the literature24.

where Δ represents the gap size. The first term is the energy independent single particle scattering rate and the second term is the BCS self energy. Γ0 represents the inverse electron pair lifetime. The spectral functions, the imaginary part of the Green's functions, were calculated as follows.  , where

, where  and

and  are the real and imaginary part of the self energy. We find that a finite value of Γ0 is necessary to achieve reasonable representation of the experimental data. The simulated and experimental spectral density of states are shown by superimposing them in Figs. 6(d) and 6(e) for the He i and He ii spectra, respectively. Evidently, the simulated spectra provide a remarkable representation of the experimental spectra.

are the real and imaginary part of the self energy. We find that a finite value of Γ0 is necessary to achieve reasonable representation of the experimental data. The simulated and experimental spectral density of states are shown by superimposing them in Figs. 6(d) and 6(e) for the He i and He ii spectra, respectively. Evidently, the simulated spectra provide a remarkable representation of the experimental spectra.

Discussion

The experimental and calculated band structure results suggest significant hybridization between Zr 4d and B 2p states leading to similar energy distribution of the PDOS. Here, the eigenstates are primarily constituted by the linear combination of the Zr 4d and B 2p states. The antibonding bands possess large Zr 4d orbital character and appear in the unoccupied part of the electronic structure25,26. The energy bands below  forming the valence band are the bonding eigenstates consisting of dominant 2p orbital character. The covalency between these states could be attributed to the large radial extension of the 4d orbitals overlapping strongly with the neighboring states as also observed in other 4d systems27,28. The calculated results within the local density approximation are consistent with the experimental spectra - subtle differences between the experiment and theory could not be captured via inclusion of electron correlation and/or consideration of spin-orbit coupling in these LDA calculations.

forming the valence band are the bonding eigenstates consisting of dominant 2p orbital character. The covalency between these states could be attributed to the large radial extension of the 4d orbitals overlapping strongly with the neighboring states as also observed in other 4d systems27,28. The calculated results within the local density approximation are consistent with the experimental spectra - subtle differences between the experiment and theory could not be captured via inclusion of electron correlation and/or consideration of spin-orbit coupling in these LDA calculations.

The band structure results exhibit two important features - (i) the energy bands with t2g symmetry are highly dispersive compared to eg bands and (ii) the crystal field splitting is negligible. As shown in Fig. 1, the B12 dodecahedrons form an octahedra around Zr sites with the center of mass of the B12 units at the edge centers of the unit cell. The size of the dodecahedrons are quite large with no boron situating on the unit cell edge. Thus, the overlap of B 2p orbitals with the t2g orbitals is significantly enhanced due to the proximity of borons along the face diagonals, while that with the eg orbitals is reduced leading to a comparable crystal field potential on both the orbitals. The larger hybridization with the t2g orbitals are also manifested by the large dispersion of the t2g bands spanning across the Fermi level while eg bands are relatively more localized. From these calculations, the effective valency of Zr was found to vary between (+2.4) to (+2.5) depending on the electron interaction parameters such as correlation strength, spin orbit coupling etc.

The Fermi level is located almost at the inflection points of each of the energy band crossing  as shown in Fig. 7. This is verified by investigating the first derivative of the energy bands shown by the symbols in the figure. The arrows in the figure indicate Fermi level crossing and corresponding point in the first derivative curves. Evidently, the band crossing correspond to an extremum in the derivative plot. The inflection point is the point, where the curve changes its curvature that corresponds to a change in the character of the conduction electrons (the Fermi surface) from hole-like to electron-like behavior. This behavior is termed as Lifschitz transition29. Thus, this material appear to be lying in the proximity of the Lifschitz transition as also observed in various exotic unconventional superconductors such as Fe-pnictides30. Due to the lack of cleavage plane and hardness of the sample, the Fermi surface mapping of this sample could not be carried out to verify this theoretical prediction experimentally. It is well known that the band structure calculations captures the features in the electronic structure well in the weakly correlated systems as also found in the present case suggesting possibility of such interesting phenomena in this system. We hope, future studies would help to enlighten this issue further.

as shown in Fig. 7. This is verified by investigating the first derivative of the energy bands shown by the symbols in the figure. The arrows in the figure indicate Fermi level crossing and corresponding point in the first derivative curves. Evidently, the band crossing correspond to an extremum in the derivative plot. The inflection point is the point, where the curve changes its curvature that corresponds to a change in the character of the conduction electrons (the Fermi surface) from hole-like to electron-like behavior. This behavior is termed as Lifschitz transition29. Thus, this material appear to be lying in the proximity of the Lifschitz transition as also observed in various exotic unconventional superconductors such as Fe-pnictides30. Due to the lack of cleavage plane and hardness of the sample, the Fermi surface mapping of this sample could not be carried out to verify this theoretical prediction experimentally. It is well known that the band structure calculations captures the features in the electronic structure well in the weakly correlated systems as also found in the present case suggesting possibility of such interesting phenomena in this system. We hope, future studies would help to enlighten this issue further.

The high resolution spectra close to the Fermi level indeed exhibit deviation from Fermi liquid behavior - a suggestive of quantum instability in this system as expected from the above results. R. Lortz et al.7 showed that the resistivity of ZrB12 exhibits linear temperature dependence in a large temperature range of 50 K–300 K. The resistivity below 50 K of the normal phase is complex and does not show T2-dependence. Both, the resistivity and specific heat data exhibit signature of anharmonic mode of Zr-vibrations. All these observations indicate complexity of the electronic properties, different from a typical Fermi-liquid system consistent with the photoemission results.

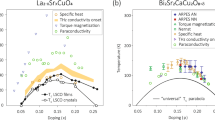

A dip appears at the Fermi level at temperatures much higher than the superconducting transition temperature reminiscent of a pseudogap feature. In order to investigate this further, we study the fitting parameters simulating the spectral functions in Fig. 8. The energy gap, Δ is found to be about 7.3 meV and remains almost unchanged in the whole temperature range studied. This gap is significantly larger than the value predicted (1–2 meV) considering BCS behavior. The magnitude of Γ1, which is a measure of single particle scattering rate, is quite large and found to decrease with the decrease in temperature. On the other hand, Γ0, the inverse pair lifetime is found to be significant and smaller than 2Δ suggesting proximity to a BCS limit for this system. Γ0 exhibits temperature dependence quite similar to that of Γ1. The decrease in Γ0 manifests gradual enhancement of the electron pair lifetime with the decrease in temperature that eventually leads to the superconducting phase upon attaining coherence among the pairs. Thus, the temperature in the vicinity of 70 K exhibiting the onset of pair formation could be the critical temperature, T* in this system. The observation of the signature of an energy gap and finite electron pair lifetime above Tc is quite similar to that observed for under-doped cuprates24 and is an indication of precursor effect in this system. Clearly, the electronic structure of this system is complex, appears to be at the crossover of BCS and unconventional behaviors and further studies are required to understand the origin of pseudogap & unusual spectral lineshape.

In summary, we studied the electronic structure of ZrB12, predicted to be a complex conventional superconductor employing high resolution photoemission spectroscopy and ab initio band structure calculations. The valence band spectra exhibit multiple features with dominant B 2p orbital character close to the Fermi level. The experimental results could be captured reasonably well within the local density approximations. The electronic states close to Fermi level have t2g symmetry and the filling of the bands is in the proximity of Lifschitz transition. The spectral lineshape near the Fermi level in the high resolution spectra exhibit deviation from typical Fermi liquid behavior. A dip at the Fermi level emerges above the superconducting transition temperature and gradually becomes prominent at lower temperatures. The analysis of the spectral functions within the phenomenological descriptions suggests finite electron pair lifetime above Tc as a signature of a precursor effect to the superconducting transition in this system.

Methods

Sample preparation and characterization

Single crystals of ZrB12 were grown by floating zone technique in a Crystal Systems Incorporated (CSI) four-mirror infrared image furnace in flowing high purity Ar gas at a pressure of 2 bar31. The quality of the crystal was confirmed and orientation was determined from x-ray Laue - diffraction images. The magnetization measurements using a Qunatum Design MPMS magnetometer show a sharp superconducting transition temperature, Tc of 6.1 K11.

Photoemission measurements

The photoemission measurements were performed using a Gammadata Scienta R4000 WAL electron analyzer and monochromatic laboratory photon sources. X-ray photoemission (XP) and ultraviolet photoemission (UP) spectroscopic measurements were carried out using Al Kα (1486.6 eV), He ii (40.8 eV) and He i (21.2 eV) photon energies with the energy resolution set to 400 meV, 4 meV and 2 meV, respectively. The melt grown sample was very hard and possesses no cleavage plane. Therefore, the sample surface was cleaned using two independent methods; top-post fracturing and scraping by a small grain diamond file at a vacuum better than 3 × 10−11 torr. Both the procedures results to similar spectra with no trace of impurity related signal in the photoemission measurements. The measurements were carried out in analyzer transmission mode at an acceptance angle of 30° and reproducibility of all the spectra was ensured after each surface cleaning cycle. The temperature variation down to 10 K was achieved by an open cycle He cryostat from Advanced Research systems, USA.

Band structure calculations

The energy band structure of ZrB12 was calculated using full potential linearized augmented plane wave method within the local density approximation (LDA) using Wien2k software32. The energy convergence was achieved using 512 k-points within the first Brillouin zone. The lattice constant of 7.4075 Å was used considering the unit cell shown in Fig. 133. In order to introduce electron-electron Coulomb repulsion into the calculation, we have employed LDA + U method with an effective electron interaction strength, Ueff (= U − J; J = Hund's exchange integral) setting J = 0 following Anisimov et al.34. Consideration of finite J did not have significant influence on the results. We have carried out the calculations for various values of electron correlation upto 6 eV for Zr 4d electrons and 4 eV for B 2p electrons. Spin-orbit interactions among the Zr 4d electrons are also considered for the calculations.

To calculate the x-ray photoemission spectrum, we have multiplied the partial density of states obtained by the band structure calculations by the corresponding photoemission cross sections for Al Kα energy. These cross-section weighted PDOS is convoluted by two Lorentzians with the energy dependent full width at half maxima (FWHM) for the hole & electron lifetime broadenings and a Gaussian with FWHM representing the resolution broadening. The sum of these spectral functions provides the representation of the experimental valence band spectrum.

References

Vishik, I. M. et al. ARPES studies of cuprate Fermiology: superconductivity, pseudogap and quasiparticle dynamics. New J. Phys. 12, 105008 (2010).

Timusk, T. & Statt, B. The pseudogap in high-temperature superconductors: an experimental survey. Rep. Prog. Phys. 62, 61–122 (1999).

Hüfner, S., Hossain, M. A., Damascelli, A. & Sawatzky, G. A. Two gaps make a high-temperature superconductor? Rep. Prog. Phys. 71, 062501 (2008).

Littlewood, P. & Kos, Ś. Focus on the Fermi surface. Nature 438, 435 (2005).

Mannella, N. et al. Nodal quasiparticle in pseudogapped colossal magnetoresistive manganites. Nature 438, 474–478 (2005).

Matthias, B. T. et al. Superconductivity and antiferromagnetism in Boron-rich lattices. Science 159, 530 (1968).

Lortz, R. et al. Specific heat, magnetic susceptibility, resistivity and thermal expansion of the superconductor ZrB12 . Phys. Rev. B 72, 024547 (2005).

Wang, Y. et al. Specific heat and magnetization of a ZrB12 single crystal: Characterization of a type-II/1 superconductor. Phys. Rev. B 72, 024548 (2005).

Daghero, D. et al. Andreev-reflection spectroscopy in ZrB12 single crystals. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 17, S250–S254 (2004).

Gasparov, V. A., Sidorov, N. S. & Zverǩova, I. I. Two-gap superconductivity in ZrB12: Temperature dependence of critical magnetic fields in single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 73, 094510 (2006).

Biswas, P. K. Studies of Unconventional Superconductors. Ph. D. Thesis (University of Warwick, Warwick, 2012).

Thakur, S. et al. Surface bulk differences in a conventional superconductor, ZrB12 . J. Appl. Phys. 114, 053904 (2013).

Tsindlekht, M. I. et al. Tunneling and magnetic characteristics of superconducting ZrB12 single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 69, 212508 (2004).

Khasanov, R. et al. Anomalous electron-phonon coupling probed on the surface of superconductor ZrB12 . Phys. Rev. B 72, 224509 (2005).

Leviev, G. I. Low-frequency response in the surface superconducting state of single-crystal ZrB12 . Phys. Rev. B 71, 064506 (2005).

Yeh, J. J. & Lindau, I. Atomic subsheell photoionization cross sections and asymmetry parameters: 1≤ Z ≤ 103. At. Data and Nucl. Data Tables 32, 1 (1985).

Maiti, K. & Singh, R. S. Evidence against strong correlation in 4d transition-metal oxides CaRuO3 and SrRuO3 . Phys. Rev. B 71, 161102(R) (2005).

Efros, A. F. & Shklovskii, B. I. Coulomb gap and low temperature conductivity of disordered systems. J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 8, L49–L51 (1975).

Massey, J. G. & Lee, M. Direct observation of the Coulomb correlation gap in a nonmetallic semiconductor, Si: B. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 4266–4269 (1995).

Altshuler, B. L. & Aronov, A. G. Zero bias anomaly in tunnel resistance and electron-electron interaction. Solid State Commun. 30, 115–117 (1979).

Sarma, D. D. et al. Disorder effects in electronic structure of substituted transition metal compounds. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 4004–4007 (1998).

Kobayashi, M., Tanaka, K., Fujimori, A., Ray, S. & Sarma, D. D. Critical test for Altshuler-Aronov Theory: Evolution of the density of states singularity in double perovskite Sr2FeMoO6 with controlled disorder. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 246401 (2007).

Medicherla, V. R. R., Patil, S., Singh, R. S. & Maiti, K. Origin of ground state anomaly in LaB6 at low temperatures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 062507 (2007).

Norman, M. R., Randeria, M., Ding, H. & Campuzano, J. C. Phenomenology of the low-energy spectral function in high-Tc superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 57, R11093–R11097 (1998).

Shein, I. & Ivanovskii, A. Band structure of superconducting dodecaborides YB12 and ZrB12 . Phys. Solid State 45, 1429–1434 (2003).

Teyssier, J. et al. Optical study of electronic structure and electron-phonon coupling in ZrB12. Phys. Rev. B 75, 134503 (2007).

Maiti, K. Role of covalency in the ground-state properties of perovskite ruthenates: A first-principles study using local spin density approximations. Phys. Rev. B 73, 235110 (2006).

Singh, R. S. & Maiti, K. Manifestation of screening effects and A-O covalency in the core level spectra of A site elements in the ABO3 structure of Ca1−xSrxRuO3 . Phys. Rev. B 76, 085102 (2007).

Lifshitz, I. M. Anomalies of electron characteristics of a metal in the high pressure region. Sov. Phys. JETP 11, 1130–1135 (1960).

Liu, C. et al. Evidence for a Lifshitz transition in electron-doped iron arsenic superconductors at the onset of superconductivity. Nat. Phys. 6, 419–423 (2010).

Balakrishnan, G., Lees, M. R. & Paul, D. M. K. Growth of large single crystals of rare earth hexaborides. J. Crystal Growth 256, 206–209 (2003).

Blaha, P., Schwarz, K., Madsen, G. K. H., Kvasnicka, D. & Luitz, J. WIEN2k An Augmented Plane Wave + Local Orbitals Program for Calculating Crystal Properties. Schwarz K. (ed.) (Techn. Universität, Wien, 2001).

Paderno, B., Liashchenko, A. B., Filippov, V. B. & Dukhnenko, A. V. Advantages and Challenges, Science for Materials in the Frontier of Centuries Skorokhod V. V. (ed.) 347–348 (Kiev: IPMS, 2002).

Anisimov, V. I., Solovyev, I. V., Korotin, M. A., Czyzyk, M. T. & Sawatzky, G. A. Density-functional theory and NiO photoemission spectra. Phys. Rev. B 48, 16929–16934 (1993).

Acknowledgements

The authors, K. M. and N. S. acknowledge financial support from the Department of Science and Technology under the Swarnajayanti Fellowship Programme. One of the author, G. B. wishes to acknowledge financial support from EPSRC, UK (EP/I007210/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.T. carried out the measurements, band structure calculations, data analysis and helped in manuscript preparation. D.B. and N.S. carried out photoemission measurements. P.K.B. and G.B. prepared the sample and characterized it. K.M. initiated the study, supervised the measurements, helped in data analysis, prepared the figures & the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Thakur, S., Biswas, D., Sahadev, N. et al. Complex spectral evolution in a BCS superconductor, ZrB12. Sci Rep 3, 3342 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03342

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03342

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

, (b)

, (b)  and (c)

and (c)  .

.