ABSTRACT

We present 2603 spectra of 462 nearby Type Ia supernovae (SNe Ia), including 2065 previously unpublished spectra, obtained during 1993–2008 through the Center for Astrophysics Supernova Program. There are on average eight spectra for each of the 313 SNe Ia with at least two spectra. Most of the spectra were obtained with the FAST spectrograph at the Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory 1.5 m telescope and reduced in a consistent manner, making this data set well suited for studies of SN Ia spectroscopic diversity. Using additional data from the literature, we study the spectroscopic and photometric properties of SNe Ia as a function of spectroscopic class using the classification schemes of Branch et al. and Wang et al. The width–luminosity relation appears to be steeper for SNe Ia with broader lines, although the result is not statistically significant with the present sample. Based on the evolution of the characteristic Si ii λ6355 line, we propose improved methods for measuring velocity gradients, revealing a larger range than previously suspected, from ∼0 to ∼400  considering the instantaneous velocity decline rate at maximum light. We find a weaker and less significant correlation between Si ii velocity and intrinsic B − V color at maximum light than reported by Foley et al., owing to a more comprehensive treatment of uncertainties and host galaxy dust. We study the extent of nuclear burning and the presence of unburnt carbon in the outermost layers of the ejecta and report new detections of C ii λ6580 in 23 early-time SN Ia spectra. The frequency of C ii detections is not higher in SNe Ia with bluer colors or narrower light curves, in conflict with the recent results of Thomas et al. Based on nebular spectra of 27 SNe Ia, we find no relation between the FWHM of the iron emission feature at ∼4700 Å and Δm15(B) after removing the two low-luminosity SN 1986G and SN 1991bg, suggesting that the peak luminosity is not strongly dependent on the kinetic energy of the explosion for most SNe Ia. Finally, we confirm the correlation of velocity shifts in some nebular lines with the intrinsic B − V color of SNe Ia at maximum light, although several outliers suggest a possible non-monotonic behavior for the largest blueshifts.

considering the instantaneous velocity decline rate at maximum light. We find a weaker and less significant correlation between Si ii velocity and intrinsic B − V color at maximum light than reported by Foley et al., owing to a more comprehensive treatment of uncertainties and host galaxy dust. We study the extent of nuclear burning and the presence of unburnt carbon in the outermost layers of the ejecta and report new detections of C ii λ6580 in 23 early-time SN Ia spectra. The frequency of C ii detections is not higher in SNe Ia with bluer colors or narrower light curves, in conflict with the recent results of Thomas et al. Based on nebular spectra of 27 SNe Ia, we find no relation between the FWHM of the iron emission feature at ∼4700 Å and Δm15(B) after removing the two low-luminosity SN 1986G and SN 1991bg, suggesting that the peak luminosity is not strongly dependent on the kinetic energy of the explosion for most SNe Ia. Finally, we confirm the correlation of velocity shifts in some nebular lines with the intrinsic B − V color of SNe Ia at maximum light, although several outliers suggest a possible non-monotonic behavior for the largest blueshifts.

Export citation and abstract BibTeX RIS

1. INTRODUCTION

Type Ia supernovae (SNe Ia) have received much attention due to their use as distance indicators on cosmological scales and the subsequent discovery of cosmic acceleration (Riess et al. 1998; Perlmutter et al. 1999). Their astrophysical nature, however, remains perplexing to this day. The standard model of SNe Ia involves the thermonuclear disruption of a carbon–oxygen (C/O) white dwarf (WD) star (Hoyle & Fowler 1960; this has been confirmed by recent observations of the nearby Type Ia SN 2011fe in M101; Nugent et al. 2011; Bloom et al. 2012) as it approaches the Chandrasekhar mass (MCh ≈ 1.4 M☉). To do so the WD either accretes material from a non-degenerate binary companion (the "single-degenerate" scenario) or merges with another WD star (the "double-degenerate" scenario; Iben & Tutukov 1984; Webbink 1984). Both scenarios constitute plausible progenitor channels, and can accommodate variations in the total mass of the binary system (i.e., sub- and super-MCh; see Howell 2011 for a recent review).

The favored explosion mechanism involves the transition from a turbulent subsonic burning front propagating via thermal conductivity (known as a deflagration, e.g., Nomoto et al. 1984) to a supersonic detonation propagating via a strong shock (Khokhlov 1991). The deflagration phase synthesizes iron-peak elements, of which 56Ni is needed to power the light curve through the 56Ni→56Co→56Fe decay chain. It also pre-expands the WD so that the subsequent detonation burns the leftover C/O fuel at lower densities and synthesizes sufficient amounts of intermediate-mass elements (IMEs; e.g., Si, S, Ca) at high expansion velocities, which are needed to reproduce observed spectra (e.g., Branch et al. 1982). Recent multi-dimensional simulations highlight the importance of hydrodynamical instabilities during the deflagration phase (e.g., Gamezo et al. 2005; Röpke & Niemeyer 2007) and provide a physical basis for the deflagration-to-detonation transition (DDT; e.g., Woosley et al. 2009), although this DDT is artificially triggered based on pre-defined criteria (see, e.g., Kasen et al. 2009; but see Poludnenko et al. 2011 for three-dimensional simulations of spontaneous DDTs in unconfined media).

Since the first spectrophotometric measurements of an SN Ia (SN 1972E; Kirshner et al. 1973), detailed observational studies of individual objects have revealed a wide range of photometric and spectroscopic properties, including luminous 1991T/1999aa-like events (e.g., Filippenko et al. 1992b; Garavini et al. 2004), faint 1991bg-like SNe (e.g., Filippenko et al. 1992a; Leibundgut et al. 1993; Garnavich et al. 2004; Taubenberger et al. 2008), peculiar 2002cx-like events (e.g., Li et al. 2003; Phillips et al. 2007), and high-luminosity SNe Ia speculated to originate from super-Chandrasekhar-mass progenitors (e.g., Howell et al. 2006; Scalzo et al. 2010). This observed diversity contrasts with the apparent homogeneity of the SN Ia class, the majority of which seems to obey an empirical relation between the peak luminosity and the width of the light curve (the so-called width–luminosity relation or WLR; Pskovskii 1977; Phillips 1993), which is needed to normalize SN Ia luminosities for precise distance measurements. Several large sets of optical SN Ia light curves have already been published (Hamuy et al. 1996; Riess et al. 1999; Jha et al. 2006; Hicken et al. 2009; Contreras et al. 2010; Ganeshalingam et al. 2010; Stritzinger et al. 2011), but until the recent publication of 432 spectra of 32 SNe Ia by Matheson et al. (2008), there had been no large homogeneous spectroscopic data sets of nearby SNe Ia available.

The SN group at the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) initiated an ambitious observational program in 1993 (PI: R. P. Kirshner) using the telescopes at the Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory (FLWO) on Mount Hopkins, Arizona. The aims of the CfA SN Program are to obtain well-sampled light curves and multi-epoch spectroscopy of nearby (z < 0.015) SNe of all types, to study their astrophysical nature, and to provide a homogeneous low-redshift sample for cosmological analyses using SNe Ia. We follow SNe announced in IAU circulars,12 discovered for the most part by the Lick Observatory Supernova Search (LOSS) using the robotic Katzman Automatic Imaging Telescope (KAIT; Filippenko et al. 2001) and by dedicated amateur astronomers. In return we provide spectroscopic classifications for a large fraction of SN discoveries: During 1997–2007, we classified over 40% of all nearby SNe visible from Mount Hopkins and announced our results in 499 IAU circulars. These prompt classifications are important to the community and serve as the basis for triggers of other SN follow-up programs (e.g., by the Swift SN group; Milne et al. 2010).

We were not able to follow up all SNe announced in circulars, and so had to prioritize our follow-up strategy. We assigned the highest priority to (1) SNe Ia discovered before maximum light (we sometimes relaxed this requirement to follow up peculiar objects), (2) bright Type Ib/c SNe, to study both individual objects (e.g., SN 2006aj, Modjaz et al. 2006; SN 2008D, Modjaz et al. 2009) and the connection of broad-line SNe Ic with gamma-ray bursts (e.g., Modjaz et al. 2008), and (3) bright Type IIP SNe discovered within ∼2 weeks from explosion for distance determinations via a variant of the Expanding Photosphere Method (Kirshner & Kwan 1974; e.g., Dessart et al. 2008).

We have already published several large collections of optical SN Ia light curves obtained with the FLWO 1.2 m telescope (CfA1: 22 BVRI light curves, Riess et al. 1999; CfA2: 44 UBVRI light curves, Jha et al. 2006; CfA3: 185 UBVRr'Ii' light curves, Hicken et al. 2009), as well as a sample of 21 near-infrared (NIR; JHKs) light curves obtained with the robotic PAIRITEL 1.3 m telescope (Wood-Vasey et al. 2008). Spectra of individual SNe Ia have been published in several papers (SN 1998aq, Branch et al. 2003; SN 1998bu, Jha et al. 1999b; SN 1999by, Garnavich et al. 2004; SN 2001ay, Krisciunas et al. 2011; SN 2001eh and SN 2001ep, Sauer et al. 2008; SN 2002cx, Li et al. 2003; SN 2005cf, Wang et al. 2009b; SN 2006bt, Foley et al. 2010; SN 2006gz, Hicken et al. 2007), including the large sample of 432 spectra of 32 SNe Ia (including SN 1998aq and SN 1998bu) published by Matheson et al. (2008). A study of the use of spectroscopic indicators in determining distances to SNe Ia in the Hubble flow was published by Blondin et al. (2011b), based on 47 spectra of 26 SNe Ia (including 15 spectra of nine SNe Ia from the Matheson et al. 2008 sample).

Here, we present the second large release of SN Ia spectra from the CfA SN Program taken between 1993 October and 2008 August. This sample consists of 2603 spectra of 462 SNe Ia, of which 2065 spectra of 406 SNe Ia are published here for the first time. It includes new reductions of spectra taken during 1994–1997 of SNe Ia that were part of the CfA1 light-curve sample. Unlike Matheson et al. (2008), we include spectra of all SNe Ia13 taken during this 15 year period, regardless of sampling and whether or not a well-calibrated light curve was available. The main reason for doing so is that a large fraction of the 149 SNe Ia for which we only have a single spectrum were classified by us, and we wish their spectra to be publicly available. Another reason is that other groups might have well-sampled light curves of objects for which we were unable to determine a time of maximum light, adding value to the "phaseless"14 spectra presented here.

The resulting sample spans a large range of SN Ia properties and is ideal for studies of spectroscopic diversity, which is the aim of this paper. In Section 2, we present the spectroscopic observations and data reduction techniques. Section 3 comments on the general properties of the CfA sample of 462 SNe Ia. In Section 4, we present the spectroscopic classification schemes of Branch et al. (2006) and Wang et al. (2009a), and study the properties of SNe Ia in these different subclasses. Section 5 focuses on the characteristic Si ii λ6355 line of SNe Ia, studying its velocity evolution and relation to intrinsic color. In Section 6, we analyze the extent of nuclear burning and the presence of high-velocity features (HVFs) and unburnt carbon in early-time spectra. Section 7 examines the relation between the FWHM of nebular iron lines and luminosity, and between nebular line shifts and intrinsic properties of SNe Ia at maximum light. Conclusions follow in Section 8.

All 2603 spectra presented in this paper will be made publicly available through the CfA Supernova Archive.15

2. OBSERVATIONS AND DATA REDUCTION

In this section, we summarize our observational strategy and data reduction methods. These are essentially identical to the ones presented by Matheson et al. (2008), but we highlight a few differences and provide additional information when needed.

2.1. Observations

As with the sample of 432 spectra published by Matheson et al. (2008), the majority of spectra presented here (2447 out of 2603 spectra or ∼94%) were obtained with the FAST spectrograph (Fabricant et al. 1998) mounted on the Tillinghast 1.5 m telescope at FLWO. The FAST spectrograph has been operational since 1994 January and the first SN Ia spectrum was one of SN 1994D taken on 1994 March 10 (all dates are given in UT). The observations were carried out in queue-scheduled mode, for the most part by two professional observers (P. Berlind and M. L. Calkins, who observed ∼72% of the FAST spectra presented here), as well as by CfA personnel. A total of 79 individual observers contributed to the FAST SN Ia sample presented here. During 1997–2008, typically 2–3 spectra were taken each night FAST was scheduled on the FLWO 1.5 m, namely, ∼20 nights per month, excluding August which corresponds to the annual shutdown at FLWO during the monsoon season. During 1994–1996, typically a single spectrum was taken in any given night. Observational details of the spectra are given in Table A1.

The usual setup for observations with FAST consisted of a ruled grating with 300 lines per mm and a 3'' slit, yielding a typical FWHM resolution of 6–7 Å over a wavelength range of ∼3700 to ∼7500 Å. From 2004 September onward (starting with observations of SN 2004dt), we changed the standard setup, extending it down to ∼3500 Å to cover the entire Ca ii H&K absorption profile. For a few SNe Ia (SN 1996ai, SN 1999by, SN 1999dq, SN 2001eh, SN 2001ep, and SN 2002bo) we requested additional observations with a different grating tilt to extend the wavelength range beyond 9000 Å. Other programs in the FAST queue would sometimes request different instrument setups, either with narrower slits (1 5 and 2'') or with a higher-resolution grating (cf. spectra of SN 1995ac, SN 1998aq, SN 1998bu, SN 1999by, and SN 1999cl). For most of the observations obtained during 1994–1998, the slit was oriented at a position angle of 90°. From late 1998 onward, the slit was generally positioned at the parallactic angle (unless the object was at airmass ≲ 1.1) so as to minimize the effects of atmospheric dispersion (Filippenko 1982). Table A1 gives the slit position angle for each spectrum as well as the absolute difference, |ΔΦ|, with the actual parallactic angle.

5 and 2'') or with a higher-resolution grating (cf. spectra of SN 1995ac, SN 1998aq, SN 1998bu, SN 1999by, and SN 1999cl). For most of the observations obtained during 1994–1998, the slit was oriented at a position angle of 90°. From late 1998 onward, the slit was generally positioned at the parallactic angle (unless the object was at airmass ≲ 1.1) so as to minimize the effects of atmospheric dispersion (Filippenko 1982). Table A1 gives the slit position angle for each spectrum as well as the absolute difference, |ΔΦ|, with the actual parallactic angle.

Additional spectra were obtained during classically scheduled nights at the MMT Observatory 6.5 m telescope with the Blue Channel (131 spectra) and Red Channel (3 spectra) spectrographs (Schmidt et al. 1989). A number of different spectrograph settings were used, yielding FWHM resolutions ranging between ∼3 and ∼13 Å, with a wavelength range typically extending below 3500 Å and beyond 8000 Å. A few spectra were taken with two settings of the Blue Channel spectrograph with non-overlapping wavelength ranges. This only concerns the five MMT spectra taken on 1994 June 12 (SN 1994D, SN 1994M, SN 1994Q, SN 1994S, and SN 1994T), all of which have ∼400 Å wide gaps (∼6150–6550 Å) between the two portions of the spectra. These spectra have been clearly marked in Table A1.

Last, a few spectra were obtained with the Magellan 6.5 m Clay (+LDSS-2/LDSS-3; 21 spectra) and Baade (+IMACS; one spectrum of SN 2003kf) telescopes. The FWHM resolution varies between ∼9 and ∼18 Å for LDSS-2, 9–12 Å for LDSS-3, and 5–6 Å for IMACS. The spectra taken with the Magellan 6.5 m telescopes typically do not reach bluer wavelengths than the FAST spectra, but they generally extend beyond 9000 Å.

2.2. Data Reduction

The data reduction methods are the same as those presented by Matheson et al. (2008), and we refer the reader to that paper for complementary information. The FAST data were all reduced in the same consistent manner. This also applies to FAST data from 1994–1997 that were entirely re-reduced for the purposes of this paper (this enabled the recovery of two spectra of SN 1997do and SN 1997dt accidently omitted from the data set published by Matheson et al. 2008). The resulting FAST sample of 2447 spectra makes this by far the largest homogeneous SN Ia spectroscopic data set to date.

We used standard routines in IRAF16 to correct the CCD frames for overscan. The bias frames are sufficiently uniform so that we do not subtract them to avoid introducing additional noise. We did not correct for dark current as it is typically negligible with FAST. As noted by Matheson et al. (2008), however, a few spectra are affected by dark-current problems after UV flashing, resulting in a small emission feature at ∼7100 Å (observed) and increased noise in the red portion of the spectrum. For a handful of spectra taken in 1998 (SN 1998cs, SN 1998de, SN 1998ec, and SN 1998eg), the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) degradation is large enough that we have simply trimmed off affected portions of the spectra (these have been clearly marked in Table A1). The CCD frames are then flat-fielded using a combined normalized flat-field image. One-dimensional spectra are then optimally extracted using the algorithm of Horne (1986) as implemented in the IRAF apall package. These spectra are then wavelength calibrated using HeNeAr lamps taken immediately after (occasionally before) each exposure. The same procedure was applied to spectra taken with the MMT and Magellan 6.5 m telescopes, although we subtracted a combined bias frame before the flat-fielding stage. Subsequent reduction steps described below are common to all telescope/instrument combinations.

We use our own set of routines in IDL to flux calibrate the extracted one-dimensional wavelength-calibrated spectra. Aside from the actual flux calibration, these routines also apply small adjustments to the wavelength calibration based on night-sky lines in the SN frames, and apply a heliocentric correction. The spectrophotometric standard stars observed on the same night (see Table A1) are also used to remove telluric absorption features from the spectra (see, e.g., Wade & Horne 1988; Matheson et al. 2000). We did not re-reduce the 37 MMT spectra from 1993 to 1997 that were flux calibrated using standard procedures in IRAF.

Approximately 50% of the spectra listed in Table A1 were cross-calibrated with two spectrophotometric standard stars of different colors to overcome the impact of second-order light contamination. Prior to the FAST refurbishment in 2003 August, the spectrograph blocked blue light such that the FAST spectra until SN 2003gq do not suffer from this effect (FAST spectra taken between 1997 September and 2003 July were usually calibrated with a single standard star). Starting in 2003 September, two standard stars were systematically used for the flux calibration. Our new reductions of the 1994–1997 data also uses two standard stars for consistency with the 2003–2008 data set, although the impact on the resulting flux calibration is minor.

Figure 1 illustrates our flux calibration technique with two standard stars on the FAST spectrum of SN 2008bf at 1 day past B-band maximum. On the same night as a given SN observation, we observed a relatively blue standard star (here Feige 34, sdO spectral type; top panel) and a relatively red standard star (here HD 84937, sdF spectral type; middle panel). The blue standard yields a more accurate flux calibration in the blue due to a greater number of counts and the absence of a Balmer jump, which complicates the calibration around 4000 Å, while the red standard yields a better calibration in the red where it does not suffer as much from second-order contamination. One clearly sees that the blue standard Feige 34 is poorly calibrated by the red standard blueward of ∼4000 Å (top panel; red line), while applying the blue standard to calibrate the red standard HD 84937 results in a flux deficit redward of ∼6000 Å (middle panel; blue line). The SN spectrum is calibrated using both standard stars (bottom panel), and the two resulting spectra are combined in a ∼100 Å wide region around ∼4500 Å (i.e., slightly redward of the Balmer jump). Blueward (redward) of this region, the spectrum calibrated using the blue (red) standard is used. The impact on the final spectrum (bottom panel; black line) may not seem spectacular, but we clearly recover flux in the Ca ii H&K absorption region and redward of the Si ii λ6355 line.

Figure 1. Illustration of our flux-calibration procedure with one "blue" (Feige 34; top panel) and one "red" (HD 84937; middle panel) spectroscopic standard star, applied to the FAST spectrum of SN 2008bf at one day past B-band maximum (bottom panel). In all three panels, the blue (red) spectrum corresponds to a flux calibration using the blue (red) standard star. The gray shaded area highlights the wavelength interval used to combine the blue- and red-calibrated spectra of SN 2008bf. Blueward (redward) of this interval, the blue-(red-) calibrated spectrum is used to generate the final spectrum (black line). Both standard stars are also used to generate normalized telluric absorption spectra (black line in top and middle panels) which serve to remove these features (here the atmospheric B band) in the final SN spectrum (see inset in bottom panel; black line).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageWe also illustrate the removal of atmospheric absorption features, here the O2 B band around 6880 Å. Each standard star is used to derive a normalized telluric spectrum (top and middle panels; black line), which is then divided out from the SN spectrum after appropriate scaling (ratio of airmasses raised to some power α ≈ 0.6; see Wade & Horne 1988). The red standard star is more effective in removing these features, since the blue standard suffers from second-order contamination in these atmospheric bands. In this particular example the B band leaves a small imprint on the SN spectrum, but the inset in the lower panel of Figure 1 shows that this technique is successful in removing the unwanted absorption.

We can check the accuracy of the relative flux calibration of our spectra (no attempt was made to put the spectra on an absolute flux scale) by comparing the B − V color derived from photometry with that derived directly from the spectra (see Matheson et al. 2008, their Figure 4). We interpolated the corresponding B- and V-band light curves at the time each spectrum was taken, unless the difference was larger than 3 days (the interpolated measurements were visually cross-checked). FAST spectra taken before 2004 September do not extend to the blue edge of the B filter (3600 Å). We have run simulations based on the SN Ia spectral template of Hsiao et al. (2007) that show that even for spectra extending only down to 3750 Å the error on the inferred B − V color is less than 0.005 mag, so we include all the 1994–2008 FAST spectra in the comparison. The resulting 1128 B − V measurements are displayed in Figure 2. For SN spectra at phases less than 20 days past B-band maximum light taken within 10° of the parallactic angle (or at low airmass:  ; filled circles), the scatter around zero difference is ∼0.08 mag, slightly larger than the ∼0.06 mag scatter found by Matheson et al. (2008). The reason for this larger scatter is the inclusion of low-S/N spectra in our sample (S/N < 10 pixel−1). Three significant outliers (∼1 mag difference in B − V color) correspond to spectra of the 2002cx-like SN 2005cc that are contaminated by host-galaxy light.

; filled circles), the scatter around zero difference is ∼0.08 mag, slightly larger than the ∼0.06 mag scatter found by Matheson et al. (2008). The reason for this larger scatter is the inclusion of low-S/N spectra in our sample (S/N < 10 pixel−1). Three significant outliers (∼1 mag difference in B − V color) correspond to spectra of the 2002cx-like SN 2005cc that are contaminated by host-galaxy light.

Figure 2. Comparison of B − V color derived from spectra with that derived from photometric measurements (see Matheson et al. 2008, their Figure 4). We show measurements for spectra with phases less than 20 days past B-band maximum (circles), for which the difference between the position angle of the spectroscopic slit and the parallactic angle, noted |ΔΦ|, is less than (black) or greater than (blue) 10°. Spectra taken at low airmass ( ) are included in the |ΔΦ| < 10° measurements. The stars correspond to spectra at phases greater than 20 days past B-band maximum. In each case we indicate the magnitude scatter about the 1:1 relation (dashed line). The +63 day spectrum of SN 2005M has low S/N, SN 1996ai is the most highly reddened SN Ia in our sample (E(B − V) ≈ 1.8 mag), and the spectra of SN 2005cc are contaminated by host-galaxy light.

) are included in the |ΔΦ| < 10° measurements. The stars correspond to spectra at phases greater than 20 days past B-band maximum. In each case we indicate the magnitude scatter about the 1:1 relation (dashed line). The +63 day spectrum of SN 2005M has low S/N, SN 1996ai is the most highly reddened SN Ia in our sample (E(B − V) ≈ 1.8 mag), and the spectra of SN 2005cc are contaminated by host-galaxy light.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageThe scatter is ∼2 times larger for spectra not observed at the parallactic angle (|ΔΦ ⩾ 10°|), regardless of phase (open circles and open stars). The scatter is also significantly larger for SN spectra at phases greater than 20 days past maximum observed at the parallactic angle (filled stars). Possible reasons for this were already noted by Matheson et al. (2008): the spectra become dominated by prominent emission features, giving rise to systematic errors when multiplied by a filter that is not precisely matched to the photometry. The spectra are also fainter, increasing the impact of host-galaxy contamination.

We show example spectral series in Figure 3. Plots of all SNe Ia from the CfA SN Program will be made available alongside the actual data on the CfA SN Archive Web site.

Figure 3. Example SN Ia spectral series from the CfA SN Program. The flux units are fλ (erg s−1 cm−2 Å−1) that have been normalized and then additive offsets applied for clarity. The zero-flux level for each spectrum is marked with an extension on the red edge. The wavelength axis is corrected for the recession velocity of the host galaxy. The number associated with each spectrum indicates the phase in (rest-frame) days from B-band maximum. Spectra with low S/N have been binned; they are indicated with an asterisk appended to the phase label. Shown are spectra of two "normal" SNe Ia in the top row (SN 2007af and SN 2007co); one 1991bg-like (SN 2005ke), one 1991T-like (SN 2007S; the +59 day and +64 day spectra are strongly contaminated by the host galaxy), and one 2002cx-like (SN 2008A) SN Ia in the bottom row.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image3. SAMPLE PROPERTIES

We briefly summarize the properties of the SN Ia sample presented in this paper in terms of phase, redshift, and Δm15(B) distributions, as well as the typical number of spectra per SN. We cross-checked the classifications of all SNe in our sample with those reported in circulars using the SNID code of Blondin & Tonry (2007). Three SNe Ia have no previously reported classifications: SN 2001es, SN 2003de, and SN 2004cu. One SN Ia (SN 1999bv) was misclassified as a "probable Type Ib/c" SN by Jha et al. (1999a), although its spectrum shows it to be a Type Ia SN at ∼3 months past maximum light (as noted by Matheson et al. 2001). All other SNe in our sample are classified as Type Ia in circulars.

We were able to determine a reliable time of B-band maximum (tmax(B); see Table 1) for 271 out of 462 SNe Ia, based for the most part on photometry from the CfA (Riess et al. 1999; Jha et al. 2006; Hicken et al. 2009) and from the LOSS (Ganeshalingam et al. 2010). We rely on a number of light-curve fitters for this purpose: MLCS2k2 (Jha et al. 2007), SALT2 (Guy et al. 2007), SNooPy (Burns et al. 2011), and the BayeSN statistical model of Mandel et al. (2009, 2011). When more than one estimate for tmax(B) is available, we simply take the mean value. For a few SNe we used values from the literature, in particular results from SNooPy fits to light curves from the Carnegie Supernova Program (CSP; Contreras et al. 2010; Stritzinger et al. 2011) by Burns et al. (2011) and Stritzinger et al. (2011). Estimates for six SNe Ia (SN 2001gc, SN 2002es, SN 2007fb, SN 2007fs, SN 2007kk, and SN 2008ae) were provided by the Berkeley SN group based on LOSS light curves (M. Ganeshalingam et al. 2011, private communication), while tmax(B) values for four of the five SNF SNe Ia in our sample were provided by the SNfactory collaboration (S. Bailey 2011, private communication). We thus have 191 SNe Ia with no reliable time of maximum (24 of which have B-band light curves). While this represents a sizeable fraction of the total number of individual SNe Ia in our sample, it is only a modest percentage of the total number of spectra (397 in 2603 spectra or ∼16%).

Table 1. Basic SN Parameters

| SN | za | tmax(B)b | Δm15(B)c | MBd | B − Ve | Bmax − Vmaxf | Phot. Ref.g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993ac | 0.0503 | 49269.2 (1.2) [Jha07] | 1.19 (0.10) [Phi99] | ... | ... | ... | CfA1 |

| 1993ae | 0.0190 | ...h | ... | ... | ... | ... | CfA1 |

| 1994D | 0.0029 | 49432.5 (0.1) [B,M,SA,SN] | 1.37 (0.03) [B] | ... | ... | ... | Jha07 |

| 1994M | 0.0232 | 49474.5 (0.9) [B,M,SA,SN] | 1.26 (0.06) [B] | −19.21 (0.08) | −0.11 (0.06) | −0.10 (0.06) | CfA1 |

| 1994Q | 0.0295 | 49496.2 (1.1) [Jha07] | 1.03 (0.10) [Phi99] | ... | ... | ... | CfA1 |

| 1994S | 0.0151 | 49518.3 (0.3) [B,M,SA,SN] | 0.94 (0.06) [B] | −19.55 (0.09) | −0.12 (0.05) | −0.11 (0.05) | CfA1 |

| 1994T | 0.0346 | 49514.4 (0.4) [M,SN] | 1.51 (0.08) [SN] | ... | ... | ... | CfA1 |

| 1994ae | 0.0043 | 49685.5 (0.8) [B,M,SA,SN] | 0.96 (0.04) [B] | ... | ... | ... | CfA1,Jha07 |

| 1995D | 0.0067 | 49768.7 (0.1) [B,M,SA,SN] | 1.05 (0.03) [B] | ... | ... | ... | CfA1,Jha07 |

| 1995E | 0.0120 | 49775.2 (0.5) [B,M,SA,SN] | 1.16 (0.05) [B] | ... | ... | ... | CfA1 |

Notes. aHeliocentric redshift as reported in NED (except for the redshifts given in Table 3). bMJD at the B-band maximum light. The 1σ error is given in between parentheses. The fitters used to determine tmax(B) are given in between square brackets: B: BayeSN (Mandel et al. 2009); M: MLCS2k2 (Jha et al. 2007); SA: SALT2 (Guy et al. 2007); SN: SNooPy (Burns et al. 2011). References to estimates taken from the literature are given below. In the case of multiple tmax(B) estimates the error is given as the standard deviation of the individual values. For cases where no error information was available we assume a typical 0.5 day uncertainty. cΔm15(B) decline rate in magnitudes. The 1σ error is given in between parentheses. The fitter used to determine Δm15(B) is given in the square brackets (see above). We assign a minimum 0.05 mag uncertainty to Δm15(B) estimates with SNooPy (which typically yield a formal ∼0.01 mag uncertainty). References to estimates taken from the literature are given below. dIntrinsic absolute peak B-band magnitude from BayeSN (assuming H0 = 72 km s−1 Mpc−1) for SNe Ia with zCMB ⩾ 0.01 and AV < 1 mag. eIntrinsic B − V color at the B-band maximum light from BayeSN for SNe Ia with zCMB ⩾ 0.01 and AV < 1 mag. fIntrinsic Bmax − Vmax pseudocolor from BayeSN for SNe Ia with zCMB ⩾ 0.01 and AV < 1 mag. gReferences for published photometric data used to determine tmax(B) and Δm15(B) (see below). References to "Jha07" are meant to point the reader to references given in Table 1 of Jha et al. (2007). hJha et al. (2007) give tmax(B) = 49288.08 ± 1.19, but the fit is uncertain (first photometric point > + 10 days past B-band maximum). iJha et al. (2007) give tmax(B) = 50630.25 ± 0.98 and Δm15(B) = 1.02 ± 0.10, but the fit is uncertain (first photometric point > + 10 days past B-band maximum). jJha et al. (2007) give tmax(B) = 50840.57 ± 2.02, but the fit is qualified by them as "poor." References. (BSNIP) Berkeley SN Ia Program (2011, private communication); (Buf05) Bufano et al. 2005; (Bur11) Burns et al. 2011; (CfA1) Riess et al. 1999; (CfA2) Jha et al. 2006; (CfA3) Hicken et al. 2009; (Con10) Contreras et al. 2010; (Gan10) Ganeshalingam et al. 2010; (Gan12) Ganeshalingam et al. 2012; (Hic07) Hicken et al. 2007; (Jha07) Jha et al. 2007 (and references therein); (Kas08) Kasliwal et al. 2008; (Kri10) Krisciunas et al. 2011; (Phi99) Phillips et al. 1999; (Phi07) Phillips et al. 2007; (Pri09) J. L. Prieto (2009, private communication; based on the method of Prieto et al. 2006); (Sca10) Scalzo et al. 2010; (SNF) SNfactory collaboration (2011, private communication); (Str11) Stritzinger et al. 2011; (Tau08) Taubenberger et al. 2008.

Only a portion of this table is shown here to demonstrate its form and content. Machine-readable and Virtual Observatory (VO) versions of the full table are available.

Download table as: Machine-readable (MRT)Virtual Observatory (VOT)Typeset image

The resulting phase distribution of the 2206 spectra for which we have a reliable tmax(B) estimate is shown in the left panel of Figure 4 out to 150 days past maximum. Also shown is the corresponding distribution for the sample of spectra published by Matheson et al. (2008), including nine spectra that were accidently omitted from their sample (see Table A1). There are 43 spectra at phases less than −10 days, and 381 spectra within 3 days from maximum light. Many of the SNe Ia in this sample have observations starting before maximum light. The right panel of Figure 4 shows the distribution of SN phases of the first spectrum. There are 23 SNe Ia for which the spectroscopic follow-up was initiated earlier than −10 days, and 168 SNe Ia with spectra starting prior to maximum light. We also have 21 spectra of 12 SNe Ia with spectra taken later than 150 days past maximum (see Table 2).

Figure 4. Distributions of SNe Ia for which we have a reliable estimate for the time of maximum light. Left: distribution of the number of spectra as a function of phase out to 60 days past maximum light. The hatched histogram corresponds to the SN Ia sample published by Matheson et al. (2008). The inset shows spectra at phases in the range [+60,+150] days. Right: number of SNe Ia vs. the phase of the first spectrum.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTable 2. CfA SN Ia Spectra at 150 days Past Maximum or Latera

| SN | Phase |

|---|---|

| (days) | |

| 1994D | +611 |

| 1994ae | +152,+366 |

| 1995D | +275,+283 |

| 1998aq | +209,+229,+239 |

| 1998bu | +178,+189,+207,+216,+242 |

| 2000cx | +154,+181 |

| 2002bo | +310 |

| 2002cx | +308 (low S/N) |

| 2003kf | +397 |

| 2006X | +150 |

| 2007af | +301 |

| 2007sr | +190 |

Note. aSee Table A1 for more observational details.

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

A clearer measure of the scientific potential of this sample is the number of SNe with at least N spectra. Figure 5 shows the corresponding distribution, for all 462 SNe Ia in our sample (solid line) and for the 191 with no time of maximum (dotted line). There are 92 SNe Ia for which we have at least 10 spectra, three of which have no reliable tmax(B) (SN 2002bz, SN 2003fd, and SN 2003iu). There are 20 SNe Ia with at least 20 spectra, and four objects with over 30 spectra (SN 1998bu, SN 2001V, SN 2002bo, and SN 2007af). There are on average eight spectra for each of the 313 SNe Ia with at least two spectra.

Figure 5. Number of SNe Ia with a least N spectra. The solid line is for all SNe Ia, while the dotted line corresponds to SNe Ia with no reliable estimate for the time of maximum.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageThe redshift distribution of our sample is shown in Figure 6. The median redshift is ∼0.023, and 361 SNe Ia are at z > 0.015 (nearby Hubble flow). The highest-redshift SN Ia in our sample, SN 1996ab at z ≈ 0.123, is part of the CfA1 light-curve sample of Riess et al. (1999). Nearly all redshifts are from the corresponding host galaxy as reported in the NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database (NED; ∼40% are from the Updated Zwicky Catalog of Falco et al. 1999). For a few objects there is no NED redshift for the host galaxy, and we then determine our own redshift based on narrow emission or absorption lines from the host galaxy (either in the SN spectrum itself or on a separate host-galaxy spectrum; see Table 3), using the IRAF RVSAO package of Kurtz & Mink (1998). When no such lines are visible in the SN spectrum, we resort to cross-correlation with a library of SN spectra using SNID, and report the median redshift based on the top-five matches. For two SN Ia host galaxies the redshift reported by NED is in error: MCG +07-36-33, the host of SN 2003fa, has an NED redshift of 1800 km s−1 (de Vaucouleurs et al. 1991), where we measure z = 0.0404 (cz = 12, 125 km s−1; see Table 3) based on five emission lines (including [O ii] λ3727 and Hα). The host of SN 2002es, UGC 2708, has an NED redshift of 8523 km s−1 (Monnier Ragaigne et al. 2003) reported on the main page, where the correct redshift of 5394 km s−1 (de Vaucouleurs et al. 1991) is reported on the redshift subpage (this is confirmed by the Berkeley SN Group using an optical spectrum of UGC 2708; W. Li 2011, private communication). All other NED redshifts were found to be consistent with our own estimates. Four of the five SNe Ia in our sample discovered by the SNfactory occur in anonymous hosts. We derive their heliocentric redshifts based on the CMB-frame redshifts given in Table 2 of Bailey et al. (2009) and the coordinates as reported on the SNfactory Supernova Discoveries Web site.

Figure 6. Redshift distribution for the 462 SNe Ia in our sample. The hatched histogram corresponds to the SN Ia sample published by Matheson et al. (2008). There are four SNe Ia at redshifts larger than 0.075: SN 1999ce, SN 2006bu (part of the CfA3 light-curve sample), SN 2001bp, and SN 1996ab (part of the CfA1 light-curve sample).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTable 3. SN Redshifts not taken from NED

| SN | Host | z | Ref.a |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1993ac | CGCG 307-023 | 0.0503b | abs |

| 1996ab | Anonymous | 0.123c | SNID |

| 1998ex | MCG +11-10-16 | 0.0365 | em |

| 2000dl | UGC 1191 | 0.0611 | abs |

| 2001eo | UGC 3963 | 0.066 | SNID |

| 2001es | 2MASX J2020834+1905246 | 0.0420 | em |

| 2002hu | MCG +06-6-12 | 0.0374 | em |

| 2003fa | MCG +07-36-33 | 0.0404d | em |

| 2003hw | 2MASX J03014982+3544343 | 0.0420 | abs |

| 2004gz | MCG +10-23-45 | 0.0137 | em |

| 2005ch | Anonymous | 0.027 | SNID |

| 2005lz | UGC 1666 | 0.040 | SNID |

| 2006bu | 2MASX J13524703+0518496 | 0.081 | SNID |

| 2007H | Anonymous | 0.0426 | em |

| 2007cq | 2MASX J22144070+0504435 | 0.0262 | em |

| 2007if | Anonymous | 0.0742e | 1 |

| 2007kf | Anonymous | 0.044 | SNID |

| 2007kg | 2MFGC 18005 | 0.006 | SNID |

| 2007qe | Anonymous | 0.0239 | em |

| 2008E | Anonymous | 0.034f | 2 |

| SNF20080522-000 | Anonymous | 0.0450g | 3 |

| SNF20080522-011 | Anonymous | 0.0379g | 3 |

| SNF20080623-001 | Anonymous | 0.0430g | 3 |

| SNF20080720-001 | Anonymous | 0.0209g | 3 |

Notes. aem: emission lines from the host galaxy in our own spectrum; abs: absorption lines from the host galaxy in our own spectrum; SNID: cross-correlation with SN Ia spectral templates using the SNID code of Blondin & Tonry (2007; typical error <0.005). bNED reports a redshift z = 0.049 based on the host-galaxy redshift given in IAUC 5882 (Schmidt et al. 1993). We have re-derived the redshift using the same spectrum of the host galaxy as Schmidt et al. (1993). cNED reports an approximate redshift z = 0.13 based on the blueshift of the Si ii λ5972 line (assumed to be 10,000 km s−1 in IAUC 6405; Garnavich et al. 1996); Riess et al. (1999) give log (cz) = 4.571, or cz = 37,239 km s−1 (z = 0.1242), "from (their) spectra of the host galaxies;" last, Jha et al. (2007) give cz = 37,109 km s−1 (z = 0.1238). There are no obvious galaxy lines in our spectrum of SN 1996ab nor could we find a spectrum of its host galaxy. dNED reports an erroneous redshift of cz = 1800 km s−1 (z = 0.0060) for MCG +07-36-33. eScalzo et al. (2010) report z = 0.07416 ± 0.00082 based on [O ii] λ3727 and Hα. fRedshift of a nearby galaxy cluster; the SN spectrum is consistent with this redshift. gBailey et al. (2009) report the CMB-frame redshift for this SN. We derived a heliocentric redshift using its coordinates as reported on the SNfactory Supernova Discoveries Web site. References. (1) Scalzo et al. 2010; (2) Yuan et al. 2008; (3) Bailey et al. 2009.

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

The distribution of the light-curve width parameter Δm15(B)17 is shown in Figure 7 (see also Table 1). Of the 271 SNe Ia in our sample with tmax(B) information, 247 have a reliable Δm15(B) estimate. For most SNe we use the Δm15(B) inferred from our own BayeSN (185) or SNooPy (23) fits (we checked these were consistent with previously published values). For the remaining 39 objects, we take Δm15(B) values published in the literature (mostly from Jha et al. 2006; Ganeshalingam et al. 2010; Burns et al. 2011; Stritzinger et al. 2011). Our sample covers a large range in Δm15(B), from luminous SNe Ia with Δm15(B) ≈ 0.7 mag to faint ones with Δm15(B) ≳ 2.0 mag. There are 26 SNe in our sample with 1991T/1999aa-like spectra, while 34 have spectra similar to SN 1991bg or SN 1986G. Of the three SNe Ia with the smallest Δm15(B) in our sample, two (SN 2006gz, Hicken et al. 2007 and SN 2007if, Scalzo et al. 2010) were speculated to originate from super-Chandrasekhar-mass progenitors.

Figure 7. Histogram of the 247 SNe Ia for which we have a reliable Δm15(B) measurement. The hatched histogram corresponds to the SN Ia sample published by Matheson et al. (2008). There are four SNe Ia with Δm15(B) ≈ 0.7 mag (SN 2001ay, SN 2005lu, SN 2006gz, and SN 2007if) and three SNe Ia with Δm15(B) ≈ 2 mag (SN 1999by, SN 2006bz, and SN 2007hj).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image4. SPECTROSCOPIC SUBCLASSES

We investigate how SNe Ia can be classified into various subclasses based on their spectra, using the classification schemes of Branch et al. (2006) and Wang et al. (2009a). We also attempt to quantify the spectroscopic and photometric variation within each subclass. Last, we present updated correlations of several spectroscopic indicators with Δm15(B). The results in this section are largely based on spectra from the CfA SN Program (see Section 3), but we complement them with published data from the literature, whose references are given in Table A2.

4.1. Branch and Wang Classification Schemes

4.1.1. Branch et al. (2006) Classification

Branch et al. (2006) presented a new classification scheme for SNe Ia based on measurements of the pseudo equivalent widths (pEWs) of absorption features near 5750 Å and 6100 Å (generally attributed to Si ii λ5972 and Si ii λ6355, respectively) in their maximum-light spectra. The overall shape of the Si ii λ6355 absorption also enters this classification scheme. They divided SNe Ia into four subgroups based on their position in this two-dimensional parameter space, but noted the absence of strict boundaries between them, suggesting that the different subgroups were not physically distinct but instead corresponded to a continuous distribution of properties (with the possible exception of SN 2002cx-like events).

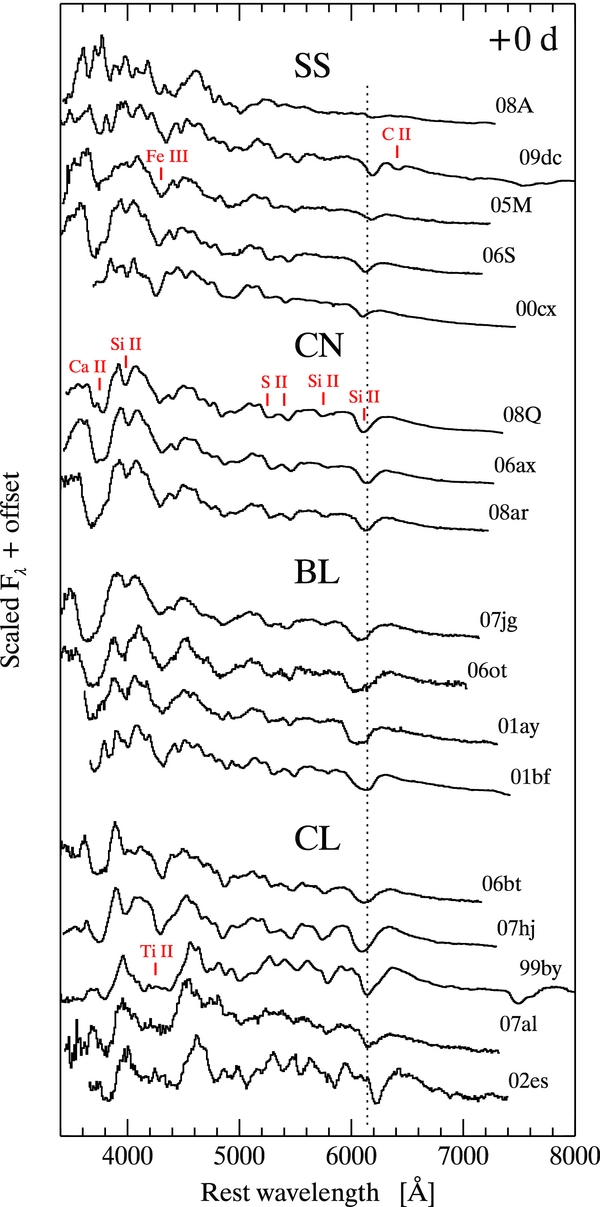

Figure 8 (left) shows the pEW of the Si ii λ5972 line versus that of the Si ii λ6355 line for 218 SNe Ia (see Figure 2 of Branch et al. 2009), based on spectra within 5 days from maximum light (see Table 4). The different symbols correspond to the various spectroscopic subclasses defined by Branch et al. (2006). Example maximum-light spectra within each subclass are shown in Figure 9. The exact locations of the boundaries between the different subclasses are ill-defined, but this does not affect our analysis.

Figure 8. Left: pseudo-EW of the Si ii λ5972 absorption vs. that of the Si ii λ6355 absorption within five days from maximum light. When several measurements are available for a given SN within this phase range, we only show the measurement closest to maximum light. The different symbols correspond to the various spectroscopic subclasses defined by Branch et al. (2006). The inset corresponds to the region bounded by the dotted box in the main plot. Right: pseudo-EW of the Si ii λ6355 absorption vs. the absorption velocity of the same line within 3 days from maximum light. When several measurements are available for a given SN within this phase range, we only show the measurement closest to maximum light. The different symbols correspond to the various spectroscopic subclasses defined by Wang et al. (2009a). Note that peculiar SNe Ia (e.g., SN 2002cx, SN 2005cc, SN 2005hk, SN 2008A) are not included in this classification scheme. The dotted lines correspond to the mean pseudo-EW and mean vabs of the Si ii λ6355 line for the Normal sample (open circles).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 9. Montage of representative SN Ia spectra at maximum light in each of the spectroscopic subclasses defined by Branch et al. (2006). We indicate tentative line identifications corresponding to the dominant ion contribution to specific absorption features (the BL subclass shares the same line identifications as the CN subclass). The vertical dotted line corresponds to Si ii λ6355 blueshifted by 10,000 km s−1. All the spectra are from the CfA SN Program, except for the spectrum of SN 2009dc (Taubenberger et al. 2011).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTable 4. SN Ia Classification using the Schemes of Branch et al. (2006) and Wang et al. (2009a)

| SN | pEW(λ5972)a | pEW(λ6355)b | vabs(λ6355)c | Phased | Branche | Wangf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Å) | (Å) | (km s−1) | (days) | Class | Class | |

| 1981B | 9.1 | 128.6 | −12050 | −1.5 | BL | N |

| 1984A | 20.4 | 200.5 | −16251 | −2.8 | BL | HV |

| 1986G | 44.4 | 122.7 | −10128 | −0.2 | CL | 91bg |

| 1989B‡ | 20.9 | 120.6 | −10634 | −1.3 | BL | N |

| 1990N | 10.9 | 87.1 | −9352 | 1.6 | CN | N |

| 1990O | 6.7 | 91.1 | −12069 | −0.9 | CN | N |

| 1991M | 18.4 | 134.4 | −12458 | 2.7 | BL | HV |

| 1991T | 0.9 | 29.0 | −9660 | −1.5 | SS | 91T |

| 1991bg | 47.9 | 95.0 | −10004 | 0.9 | CL | 91bg |

| 1992A | 19.1 | 108.9 | −14192 | −0.8 | BL | HV |

Notes. aPseudo-EW of the Si ii λ5972 absorption feature (formal uncertainty typically <1 Å). bPseudo-EW of the Si ii λ6355 absorption feature (formal uncertainty typically <1 Å). cAbsorption velocity the Si ii λ6355 absorption feature (formal uncertainty typically <100 km s−1). dPhase of measurements in rest-frame days from B-band maximum. eBranch class based on pEW(λ5972) and pEW(λ6355) within 5 days from maximum light—CN: Core Normal; BL: Broad Line; SS: Shallow Silicon; CL: Cool. We also report a classification for SNe Ia with no spectra within 5 days from maximum (but within 7 days) based on the overall shape of the Si ii λ6355 absorption feature. fWang class based on vabs(λ6355) within 7 days from maximum light (note that Figure 8 only displays measurements within 3 days from maximum)—N: Normal; HV: High-velocity; 91T: 1991T-like; 91bg: 1991bg-like. Peculiar SNe Ia (SN 2000cx, SN 2002cx, SN 2003fg, SN 2005hk, SN 2006gz, SN 2007if, SN 2008A, SN 2008ae, SN 2009dc) are not part of this classification scheme. gSN 2003fg is also known as SNLS-03D3bb (Howell et al. 2006). †Reddening and contamination by the host galaxy renders the Branch classification uncertain. ‡Branch classification differs from that reported by Branch et al. (2009; indicated in parentheses)—SN 1989B: BL (CL); SN 1999ac: CN (SS); SN 1999ee: CN (SS); SN 1999gd: CN (BL); SN 2000E: CN (SS); SN 2002er: CN (BL); SN 2005cg: CN (SS).

Only a portion of this table is shown here to demonstrate its form and content. Machine-readable and Virtual Observatory (VO) versions of the full table are available.

Download table as: Machine-readable (MRT)Virtual Observatory (VOT)Typeset image

The cluster of black dots forms the "Core Normal" (CN) subclass. SNe Ia with similar pEW(Si ii λ5972) but with broader Si ii λ6355 absorptions (characteristic of larger expansion velocities) are labeled "Broad Line" (BL). Together, these subclasses constitute the bulk of SNe Ia loosely referred to as "normal" in the literature. There is no strict boundary between the CN and BL subclasses, although the SNe Ia we classify as BL have pEW(Si ii λ6355) ≳ 105 Å. As noted by Branch et al. (2009), there is not a one-parameter sequence from the CN subclass to the more extreme BL SNe Ia (such as SN 1984A, SN 2006X, and SN 2006bq). Two SNe Ia classified as BL by Branch et al. (2009) are re-classified by us as CN (SN 1999gd, SN 2002er; see Table 4) based on the magnitude of their pEW(Si ii λ6355). We also classify SN 2009ig in the CN subclass, as opposed to the BL subclass (see Parrent et al. 2011).

The "Cool" (CL) subclass consists of SNe Ia with deeper Si ii λ5972 absorptions, often associated with low-luminosity events. They are referred to as "Cool" due to the notable absorption band around ∼4200 Å caused by lines of Ti ii, a signature of lower temperatures in the line-forming region (see, e.g., Hatano et al. 1999). The strength of this absorption band varies greatly within the CL subclass: it is strong in SN 2005ke, moderate in SN 1986G, and close to nonexistent in SN 2007au. The CL subclass contains SN 2006bt, which has a slowly declining light curve characteristic of luminous SNe Ia but with spectra displaying Ti ii absorption features characteristic of low-luminosity SNe Ia (Foley et al. 2010). It also includes SN 2004eo, labeled "transitional" by Pastorello et al. (2007) due to its intermediate properties between normal and low-luminosity SNe Ia. Based on its resemblance to SN 2004eo, Branch et al. (2009) classified SN 1989B as a CL SN Ia despite its shallower Si ii λ5972 absorption. This SN also displays narrower features in the 4600–5100 Å spectral region, indicative of lower ejecta expansion velocities. However, the width of its Si ii λ6355 absorption is comparable to other BL SNe Ia, and we choose to include SN 1989B in the BL subclass (the developer of this classification scheme concurs; D. Branch 2011, private communication).

As seen from the inset in Figure 8 (left), there appears to be a continuous distribution between CL SNe Ia at the low end of the pEW(Si ii λ5972) distribution and CN and BL SNe Ia at the high end of their pEW(Si ii λ5972) distributions. However, we identify one CL SN Ia (SN 2007al) with a remarkably shallow silicon absorption. We include this SN in the CL subclass based on the presence of a prominent Ti ii absorption feature in its maximum-light spectrum (see Figure 9).

The last subclass, "Shallow Silicon" (SS), consists of SNe Ia with weak Si ii λ5972 and Si ii λ6355. It is a heterogeneous category, including luminous 1991T/1999aa-like events characterized by higher ionization lines (Fe iii), SNe Ia resulting from possible super-Chandrasekhar-mass progenitors (SNLS-03D3bb or SN 2003fg, SN 2006gz, SN 2007if, SN 2009dc), faint 2002cx-like SNe (SN 2005hk, SN 2008A), and otherwise spectroscopically "normal" events (e.g., SN 2006S). Several SNe Ia classified as SS by Branch et al. (2009) are re-classified by us as CN (SN 1999ac, SN 1999ee, SN 2000E, SN 2005cg; see Table 4) based on the magnitude of their pEW(Si ii λ6355). SN 1999ac was already noted as a borderline SS/CN by Branch et al. (2007), and its peculiar nature discussed at length by Garavini et al. (2005) and Phillips et al. (2006).

Of the 246 SNe Ia to which we assign a Branch et al. (2006) classification in Table 4, 94 (38.2%) are of the CN subclass, 74 (30.1%) are of the BL subclass, 43 (17.5%) are of the CL subclass, and 35 (14.2%) are of the SS subclass. Note that these numbers simply reflect the properties of the SN sample studied in this paper and not of the SN Ia class as a whole.

By ∼3 weeks past maximum light, spectra of SS SNe Ia are not distinguishable from those of the CN subclass at similar phases. By comparing the +19 day spectrum of the SN 1999aa to spectra of CN SNe Ia, Branch et al. (2009) found the best match to be SN 1994D at +14 days. The corresponding phase ratio (19/14 ≈ 1.36) closely matched the ratio of their B-band light curve stretch parameters (1.143/0.838 ≈ 1.36), prompting Branch et al. (2009) to suggest that SNe Ia from the CN and SS subclasses "age spectroscopically at the same rate that they decline photometrically." We have tested this hypothesis by finding the best-match CN SN Ia template to spectra of SS SNe Ia in the phase range [+19,+23] days using SNID, and plot the ratio of their phases against that of their stretch parameters (from SALT2) in Figure 10. While most SS SNe Ia indeed lie on or close to the 1:1 relation, there are a few significant outliers (including the peculiar SN 2000cx and the 1991T-like SN 1998ab), and the Pearson correlation coefficient between both ratios is only r = 0.36. We find similar results when considering SS SNe Ia at two and four weeks past maximum light, respectively. The hypothesis of Branch et al. (2009) therefore does not apply universally to SNe Ia of the SS subclass.

Figure 10. Ratio of phases of SN Ia spectra at three weeks past maximum in the SS subclass to that of the best-match SNID template in the CN subclass vs. the ratio of their B-band light-curve stretch parameters from SALT2. The labels associated with each point indicate the name of the SS supernova followed by the name of the best-match CN template. The dashed line is the 1:1 correspondence.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageThe spectroscopic properties of SNe Ia belonging to these different subclasses have been discussed at length by Branch et al. (2006, 2007, 2008) for maximum-light, pre-maximum, and post-maximum epochs, respectively, and by Branch et al. (2009) at all epochs based on a larger sample. Here, we focus on the spectroscopic variation at maximum-light. Within each subclass, we generate composite spectra using the same pre-processing as done by SNID: The individual spectra are "flattened" through division by a pseudo continuum. We then compute the mean flux in each wavelength bin, as well as the standard (and maximum) deviation from the mean. The result is a composite spectrum with error bands for each subclass, which we show in Figure 11. The large variation within the SS subclass is clearly visible throughout the optical range (3500–7500 Å). The CN subclass displays the smallest variation at any given wavelength, as expected, albeit with a noticeable variation in the strength of the Ca ii H&K absorption feature. The composite spectrum for the BL subclass reveals the presence of high-velocity components to the Si ii λ6355 line in the maximum-deviation spectrum (dark blue) in addition to the large variation blueward of ∼4000 Å as for the CN subclass (see, e.g., SN 2001bf and SN 2007jg in Figure 9). The CL composite spectrum shows the varying strength of the Ti ii absorption feature as well as the large range in depth and position of the Si ii λ6355 absorption (shallow in SN 2007al, less blueshifted in SN 2002es; see Figure 9).

Figure 11. Composite maximum-light spectra for the various spectroscopic subclasses defined by Branch et al. (2006). Individual spectra have been flattened through division by a pseudo continuum (see the text for details). The shaded bands correspond to the standard (light blue) and maximum (dark blue) deviation about the mean maximum-light spectrum. The number in between parentheses indicates the number of individual spectra that were used to generate each composite spectrum.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageIn a recent paper, Stritzinger et al. (2011) noted a similarity between the photometric properties of SN 2006ot and SN 2006bt (Foley et al. 2010): a broad light curve characteristic of luminous SNe Ia (Δm15(B) = 0.84 mag), but a weak secondary i-band maximum characteristic of low-luminosity events. They also noted major differences between both SNe in their maximum-light spectra. SN 2006bt has a deep Si ii λ5972 absorption and evidence for absorption by Ti ii, both of which are characteristic of low-luminosity SNe Ia. SN 2006ot, on the other hand, is characterized by a shallower Si ii λ5972 absorption and a broad Si ii λ6355 absorption, with no evidence for features associated with Ti ii. In the classification scheme of Branch et al. (2006), SN 2006bt belongs to the CL subclass, while SN 2006ot is an extreme BL SN Ia, reflecting these spectroscopic differences. Nonetheless, Stritzinger et al. (2011) argue that at 3–4 weeks past maximum light, the spectra of SN 2006ot are more similar to those of SN 2006bt than to those of the normal SN 2006ax (part of the CN subclass), again stressing the similarity between both SNe. At such late phases, however, differences between the various subclasses are less apparent than at maximum light, as noted by Foley et al. (2010).18 We have run SNID on the +24 day spectrum of SN 2006ot and find good matches to spectra of SNe Ia from the CN, CL, and BL subclasses at similar phases. The best-match spectrum of SN 2006bt (at +33 days) is ranked only 21st overall. Similarly, the best-match template spectrum for the +33 day spectrum of the CL SN 2006bt (Foley et al. 2010) is the CN SN 2004S (Krisciunas et al. 2007), illustrating the difficulty in distinguishing between different SN Ia subclasses at late times. If anything, SN 2006bt and SN 2006ot demonstrate how two SNe Ia with similar light-curve shapes can have very different maximum-light spectra.

4.1.2. Wang et al. (2009a) Classification

The classification scheme of Wang et al. (2009a) is based on the velocity at maximum absorption (or absorption velocity, vabs) of the Si ii λ6355 line around maximum light. It was designed to study the spectroscopic diversity among "normal" SNe Ia. We use our own measurements on the same sample of 10 SNe Ia used by Wang et al. (2009a) to define a mean vabs trend within one week from B-band maximum. SNe Ia with Si ii λ6355 absorption velocities 3σ above this mean trend (in absolute terms) are classified as "High-velocity" (HV), the remaining objects forming the "Normal" (N) subclass (see Table 4). Note that this classification scheme does not apply to luminous 1991T/1999aa-like SNe Ia nor to low-luminosity 1991bg-like events or peculiar objects (2002cx-like, possibly super-Chandrasekhar etc.). Of the 246 SNe Ia to which we assign a Wang et al. (2009a) classification in Table 4, 143 (58.1%) are of the N subclass, while 51 (20.7%) belong to the HV subclass. Again, these numbers simply reflect the properties of the SN sample studied in this paper and are not meant to reflect the SN Ia class as a whole.

This classification scheme is illustrated in Figure 8 (right), where we show the relation between the pseudo-EW of the Si ii λ6355 line versus its absorption velocity for SNe Ia with spectra within 3 days from maximum light. This figure is largely similar to Figure 2 of Wang et al. (2009a), with the Normal SNe Ia forming a cluster in the (pEW,vabs) plane, and a tail of High-velocity objects following a trend of larger pEW for larger absorption blueshifts. The mean pEW and mean vabs for the Normal sample are ∼95 Å and ∼ −11,000 km s−1, respectively, comparable to the values found by Wang et al. (2009a). At maximum light, the boundary between the N and HV subclasses is located at ∼ −12,200 km s−1. There is a large overlap between the CN subclass of Branch et al. (2006) and the Normal subclass of Wang et al. (2009a), as well as between the BL and HV subclasses (with a few exceptions such as SN 2009ig, which is part of the CN and HV subclasses). The 1991T-like objects have absorption velocities similar to the Normal subclass, but with smaller pEW. All 1991T-like SNe Ia belong to the SS subclass of Branch et al. (2006), except for the 1999aa-like SN 1999ac. SNe Ia with spectra similar to SN 1991bg also have similar velocities but on average larger pEW. Notable exceptions include SN 2007al with similar velocities but much smaller pEW (also an outlier in the CL subclass; see Figure 8, left), and SN 2002es with similar pEW but almost a factor of two lower |vabs|. This latter SN is discussed in more detail by Ganeshalingam et al. (2012). All 1991bg-like SNe Ia belong to the Cool subclass of Branch et al. (2006).

The largest measured Si ii λ6355 pEW and blueshift in Figure 8 is for SN 1984A (pEW ≈200 Å, |vabs| ≈ 16,250 km s−1). This SN is also the most extreme BL SN Ia in the classification scheme of Branch et al. (2006). We note that Wang et al. (2009a) measure pEW ≈170 Å and |vabs| ≈ 15,200 km s−1 (see their Figure 2), but their measurement is based on a non-flux calibrated spectrum directly scanned from Figure 4 of Barbon et al. (1989), biasing their pEW measurement to lower values. Moreover, their use of the classical Doppler formula (as opposed the relativistic version used in this paper; see Equation (6) in Blondin et al. 2006) leads to a ∼500 km s−1 lower blueshift when converting the wavelength at maximum absorption in Si ii λ6355 to a velocity.

4.2. Photometric Properties as a Function of Spectroscopic Class

Based on a restricted sample of nine SNe Ia from the CN subclass, Branch et al. (2009) inferred a mean absolute peak B-band magnitude of −19.48 mag with a scatter of only 0.14 mag, suggesting that SNe Ia belonging to this subclass could be true standard candles. They noted, however, that this should be tested on a larger sample of SNe Ia in the Hubble flow.

We use the BayeSN statistical models of Mandel et al. (2009, 2011) to infer the intrinsic peak absolute B-band magnitude (and hence the total extinction along the line of sight) of SNe Ia in a consistent manner (assuming a Hubble constant of H0 = 72 km s−1 Mpc−1; see Table 1). These statistical models describe the apparent distribution of light curves as a convolution of intrinsic SN Ia variations and a dust distribution. Mandel et al. (2011) modeled the intrinsic covariance structure of the full multi-band light curves, capturing population correlations between the intrinsic absolute magnitudes, intrinsic colors, and light curve decline rates over multiple phases and wavelengths, as well as the distribution of host galaxy dust and an apparent correlation between the dust extinction AV and its wavelength dependence, parameterized by RV. The models fit individual optical and NIR SN Ia light-curve data to estimate the dust extinction, apparent and absolute light curves, and intrinsic colors for each SN. These models were trained on a nearby (z < 0.07) set of SNe Ia with optical (CfA3, Hicken et al. 2009; Carnegie SN Program, Contreras et al. 2010) and NIR (PAIRITEL; Wood-Vasey et al. 2008) data, plus light curves from the literature with joint optical and NIR observations. For the fits used in this paper, we have employed the distance-redshift constraint, except where alternative distance information was used (e.g., Cepheids; see Section 7.2).

Figure 12 shows the resulting intrinsic peak MB distribution for SNe Ia at CMB-frame redshifts zCMB > 0.01 with an inferred visual extinction AV < 1 mag, for the various spectroscopic subclasses defined by Branch et al. (2006; top) and Wang et al. (2009a; bottom). The 41 SNe Ia in the CN subclass that satisfy these criteria have a mean intrinsic peak MB = −19.40 mag with σ(MB) = 0.16 mag. This is comparable to the values derived for the Normal subclass of Wang et al. (2009a) (MB = −19.38 mag; σ(MB) = 0.17 mag). The intrinsic peak MB scatter is small for the CN (or Normal) subclass, but it is in fact larger than for the SS (σ(MB) = 0.13 mag) and BL subclasses (σ(MB) = 0.15 mag; the same is also true when comparing the Normal subclass to the 91T and HV subclasses of Wang et al. 2009a). We note, however, that the SS distribution does not include faint 2002cx-like SNe Ia (which typically have MB ≳ −18 mag; e.g., MB ≈ −17.5 mag for SN 2002cx and MB ≈ −18.0 mag for SN 2005hk; see Phillips et al. 2007) nor luminous (possibly super-Chandrasekhar) events (e.g., SN 2006gz with MB ≈ −19.9, Hicken et al. 2007; or SN 2009dc with MB ≈ −20.2, Taubenberger et al. 2011) since BayeSN did not include such SNe Ia in its training set.

Figure 12. Normalized distributions of intrinsic peak absolute B-band magnitude for the various spectroscopic subclasses defined by Branch et al. (2006; top) and Wang et al. (2009a; bottom). The peak rest-frame magnitude and host-galaxy extinction were determined using the BayeSN light-curve statistical model of Mandel et al. (2011). Only SNe Ia with a CMB-frame redshift zCMB > 0.01 and an inferred visual extinction AV < 1 mag were included. In each panel we indicate the sample mean and standard deviation of the intrinsic peak MB (see also Table 5). The number of SNe Ia in each subclass is indicated in between parentheses. We do not show the distributions for the CL or 91bg subclasses since the BayeSN statistical model did not include SNe Ia with Δm15(B) > 1.6 mag in its training set. The same is true of faint 2002cx-like SNe Ia and luminous (possibly super-Chandrasekhar) events from the SS subclass.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageThe mean intrinsic peak MB increases steadily along the SS→CN→BL sequence, with a corresponding increase in the mean Δm15(B) (see Table 5). The same applies to the 91T→N→HV sequence. There is a hint of redder mean intrinsic B − V color for the BL (HV) subclass compared to the CN (N) subclass, as expected from the "brighter-bluer" relation of Tripp (1998), but the difference (0.02−0.03 mag) is small compared with the scatter (0.06–0.07 mag) within each subclass and only measurable with sample averages. Low-luminosity SNe Ia from the CL or 91bg subclasses are not included in this comparison since the BayeSN statistical model did not include SNe Ia with Δm15(B) > 1.6 mag in its training set. SNe similar to SN 1991bg have intrinsic peak B-band magnitudes ∼2 mag fainter than normal SNe Ia, with Δm15(B) ≳ 1.9 mag, and much redder intrinsic B − V colors at maximum light. A prime example is SN 2005bl, with MB ≈ −17.2 mag, Δm15(B) ≈ 1.9 mag, and (B − V)max ≈ 0.5 mag (Taubenberger et al. 2008).

Table 5. Mean Properties of SNe Ia in the Classification Schemes of Branch et al. (2006) and Wang et al. (2009a)

| Class | 〈MB〉 (σ) | 〈Δm15(B)〉 (σ) | 〈B − V〉 (σ) | NSN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSa | −19.57 (0.14) | 0.94 (0.13) | −0.11 (0.07) | 21 |

| CN | −19.40 (0.16) | 1.12 (0.18) | −0.12 (0.06) | 41 |

| BL | −19.30 (0.15) | 1.22 (0.15) | −0.10 (0.07) | 37 |

| 91T | −19.59 (0.13) | 0.93 (0.14) | −0.12 (0.07) | 13 |

| Normal | −19.38 (0.17) | 1.15 (0.21) | −0.12 (0.06) | 67 |

| HV | −19.28 (0.16) | 1.21 (0.14) | −0.09 (0.07) | 23 |

Notes. SS: Shallow silicon; CN: Core Normal; BL: Broad Line; HV: High-velocity. Cool (CL) and 1991bg-like SNe Ia are not shown here (see the text for details). aExcluding 2002cx-like SNe Ia and super-Chandrasekhar events.

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

One might wonder whether SNe Ia in different subclasses obey different width–luminosity relations (WLRs). Figure 13 (left) shows the intrinsic peak MB inferred from BayeSN fits versus Δm15(B) for the SS, CN, and BL subclasses of Branch et al. (2006). Overplotted are best-fit relations of the form MB = a[Δm15(B) − 1.1] + b for the entire sample (solid line) and for the individual subclasses (dashed and dotted lines). The coefficients of the linear fits are given in each case. The slope of the WLR gets steeper along the SS→CN→BL sequence, while the intercept corresponds to a progressively fainter fiducial intrinsic peak MB along this same sequence. The slopes and intercepts for the individual subclasses are, however, consistent within ∼1σ of one another, such that a single average WLR is adequate to describe all the subclasses (other than the CL subclass). As seen from the right panel of Figure 13, the same analysis holds when replacing (SS, CN, BL) with (91T, N, HV) for the Wang et al. (2009a) classification scheme, the only difference being the intercept for the HV subclass, which is ∼2σ larger than those for the Normal and 91T subclasses.

Figure 13. Width–luminosity relation for the various spectroscopic subclasses defined by Branch et al. (2006; left) and Wang et al. (2009a; right). We report the linear coefficients of the fit MB = a[Δm15(B) − 1.1] + b for the entire sample (solid line) and for the individual subclasses. Errors in parentheses are given in units of 0.001 and 0.001 mag for the slope and offset, respectively.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image4.3. Spectroscopic Luminosity Indicators

Several authors have studied the correlation between various spectroscopic indicators and light-curve parameters with the aim to use such indicators to improve distance measurements to SNe Ia. Blondin et al. (2011b) showed that spectroscopic indicators alone could compete with the standard light-curve parameters for distance measurements, but that combining spectra with photometry yielded no statistically significant improvement (see also Silverman et al. 2012b). Their analysis, however, was based on a small number of SNe, so that larger samples may reveal spectroscopic measurements that provide independent information on the luminosity of SNe Ia. Such correlations are also potentially useful to constrain SN Ia models (see, e.g., Blondin et al. 2011a), and we investigate the relation of three spectroscopic indicators with Δm15(B) in Figure 14.

Figure 14. Various spectroscopic indicators vs. Δm15(B). The points are coded according to the spectroscopic subclasses defined by Branch et al. (2006), as in the left panel of Figure 8. The Pearson correlation coefficient is indicated in the upper left or upper right corner of each plot. Top: spectroscopic ratio  of Nugent et al. (1995; left) and its pseudo-EW equivalent (right). Bottom: pseudo-EW of the Si ii λ4130 line (left) and spectroscopic ratio

of Nugent et al. (1995; left) and its pseudo-EW equivalent (right). Bottom: pseudo-EW of the Si ii λ4130 line (left) and spectroscopic ratio  (right; Hachinger et al. 2006).

(right; Hachinger et al. 2006).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageThe upper left panel shows the  ratio of Nugent et al. (1995; defined as the ratio of the relative absorption depth of the Si ii λ5972 line to that of Si ii λ6355), which is thought to define a temperature sequence from low-luminosity 1991bg-like SNe Ia to luminous 1991T-like events (see also Hachinger et al. 2008). The different symbols correspond to the spectroscopic subclasses defined by Branch et al. (2006), as in the left panel of Figure 8. There is a clear correlation of

ratio of Nugent et al. (1995; defined as the ratio of the relative absorption depth of the Si ii λ5972 line to that of Si ii λ6355), which is thought to define a temperature sequence from low-luminosity 1991bg-like SNe Ia to luminous 1991T-like events (see also Hachinger et al. 2008). The different symbols correspond to the spectroscopic subclasses defined by Branch et al. (2006), as in the left panel of Figure 8. There is a clear correlation of  with Δm15(B) (the Pearson correlation coefficient is r = 0.82), with some notable outliers including two SNe Ia from the CL subclass: SN 2002fb and SN 2006bt (whose peculiar nature has been discussed at length by Foley et al. 2010). At low Δm15(B), the BL SN 2001ay (the most slowly declining SN Ia to date; Krisciunas et al. 2011) and the peculiar SS SN 2006gz (possibly resulting from a double WD merger; Hicken et al. 2007) are modest outliers.

with Δm15(B) (the Pearson correlation coefficient is r = 0.82), with some notable outliers including two SNe Ia from the CL subclass: SN 2002fb and SN 2006bt (whose peculiar nature has been discussed at length by Foley et al. 2010). At low Δm15(B), the BL SN 2001ay (the most slowly declining SN Ia to date; Krisciunas et al. 2011) and the peculiar SS SN 2006gz (possibly resulting from a double WD merger; Hicken et al. 2007) are modest outliers.

The  ratio has a relatively large associated measurement error, since the relative absorption depth is measured at a specific wavelength. Using the ratio of pseudo-EW of both lines instead not only significantly reduces the error on individual measurements (since we are integrating over many wavelength bins), it also leads to a stronger and tighter relation with Δm15(B) (r = 0.86; upper right). SN 2006bt remains an outlier using the pseudo-EW ratio, but SN 2002fb now follows the linear relation defined by the bulk of the sample. As noted empirically by Hachinger et al. (2006), and later confirmed theoretically by Hachinger et al. (2008), it is the Si ii λ5972 line that drives the correlation of

ratio has a relatively large associated measurement error, since the relative absorption depth is measured at a specific wavelength. Using the ratio of pseudo-EW of both lines instead not only significantly reduces the error on individual measurements (since we are integrating over many wavelength bins), it also leads to a stronger and tighter relation with Δm15(B) (r = 0.86; upper right). SN 2006bt remains an outlier using the pseudo-EW ratio, but SN 2002fb now follows the linear relation defined by the bulk of the sample. As noted empirically by Hachinger et al. (2006), and later confirmed theoretically by Hachinger et al. (2008), it is the Si ii λ5972 line that drives the correlation of  and its pseudo-EW equivalent with Δm15(B). Using the relative absorption depth or the pseudo-EW of the Si ii λ5972 line alone leads to equally strong correlations with Δm15(B) (r = 0.79 and r = 0.85, respectively, not shown).

and its pseudo-EW equivalent with Δm15(B). Using the relative absorption depth or the pseudo-EW of the Si ii λ5972 line alone leads to equally strong correlations with Δm15(B) (r = 0.79 and r = 0.85, respectively, not shown).

The lower left panel shows the pseudo-EW of the Si ii λ4130 line versus Δm15(B) (see Bronder et al. 2008; Arsenijevic et al. 2008; Walker et al. 2011; Blondin et al. 2011b; Chotard et al. 2011). The correlation is very clear, although a nonlinear relation may need to be invoked to accommodate the CL SNe Ia at Δm15(B) ≳ 1.5 mag. The peculiar SN 2006gz is again a modest outlier, but SN 2001ay is now a significant outlier in this relation. The largest outlier however is the BL SN 2006ot (which was not a significant outlier in the  versus Δm15(B) relation), whose similarity in terms of photometric properties with SN 2006bt was noted by Stritzinger et al. (2011). We argued in Section 4.1.1 that both objects are spectroscopically distinct, and this is clearly visible in this plot, where SN 2006bt follows the same relation as the bulk of the SN Ia sample.

versus Δm15(B) relation), whose similarity in terms of photometric properties with SN 2006bt was noted by Stritzinger et al. (2011). We argued in Section 4.1.1 that both objects are spectroscopically distinct, and this is clearly visible in this plot, where SN 2006bt follows the same relation as the bulk of the SN Ia sample.

Finally, the lower right panel shows the  ratio of Hachinger et al. (2006), defined as the ratio of the pseudo-EW of the Si ii λ5972 line to that of the Fe ii λ4800 feature (see Blondin et al. 2011b, their Figure 14). The correlation with Δm15(B) is again very strong (r = 0.80). In contrast to pEW(Si ii λ4130), SN 2006bt is this time the largest outlier, while SN 2006ot lies close to the mean relation. As was the case for the

ratio of Hachinger et al. (2006), defined as the ratio of the pseudo-EW of the Si ii λ5972 line to that of the Fe ii λ4800 feature (see Blondin et al. 2011b, their Figure 14). The correlation with Δm15(B) is again very strong (r = 0.80). In contrast to pEW(Si ii λ4130), SN 2006bt is this time the largest outlier, while SN 2006ot lies close to the mean relation. As was the case for the  ratio, both SN 2001ay and SN 2006gz are modest outliers. Since

ratio, both SN 2001ay and SN 2006gz are modest outliers. Since  and the pseudo-EW equivalent of

and the pseudo-EW equivalent of  are both positively correlated with Δm15(B), one expects the pseudo-EWs of Fe ii λ4800 and Si ii λ6355 (at maximum light) to also be correlated. There is indeed a modest correlation (r = 0.60) between pEW(Si ii λ6355) and pEW(Fe ii λ4800), but the scatter is large and the relation flattens off for pEW(Fe ii λ4800) ≳ 150 Å.

are both positively correlated with Δm15(B), one expects the pseudo-EWs of Fe ii λ4800 and Si ii λ6355 (at maximum light) to also be correlated. There is indeed a modest correlation (r = 0.60) between pEW(Si ii λ6355) and pEW(Fe ii λ4800), but the scatter is large and the relation flattens off for pEW(Fe ii λ4800) ≳ 150 Å.

5. LINE VELOCITIES

We now focus on the defining Si ii λ6355 line of Type Ia SNe, studying the variation in the time evolution of its absorption velocity (Section 5.1). We propose an alternative (and in our view more robust) method to Benetti et al. (2005) for measuring velocity gradients (Section 5.2). Last, we investigate the correlation of Si ii velocity with intrinsic color at maximum light suggested by Foley & Kasen (2011) in Section 5.3.

5.1. Evolution of the Si ii λ6355 Absorption Velocity