Summary

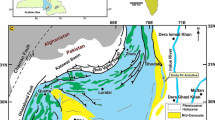

A stromatactis mud-mound has been found near Slavnické Podhorie in the Czorsztyn Unit of the Pieniny Klippen Belt (Western Carpathians, Slovakia). Its stratigraphic range is Bathonian to Callovian and it is one of the youngest known true stromatactis mud-mounds. The complete shape the mound is not visible since the klippe is a tectonic block encompassed by younger Cretaceous marls. The matrix is micritic to pelmicritic mudstone, wackestone to packstone with pelecypods, brachiopods, ammonites, and crinoids. An important component of the mound is stromatactis cavities that occur as low as the underlying Bajocian-Bathonian crinoidal limestones. The stromatactis cavities are filled by radiaxial fibrous calcite (RFC) as well as in some places by internal sediment and, finally, by clear blocky calcite. Some cavities remain open with empty voids in the centres. In some stromatactis cavities, tests of cavedwelling ostracodsPokornyopsis sp. were found, surrounded by the latest stages of the RFC. This indicates that stromatactis cavities formed an open network enabling migration of the ostracods and their larvae over a period of time.

Except in the case of the stromatactis cavities, there are numerous examples of seeming recrystallizationsensu Black (1952) and Ross et al. (1975) and Bathurst (1977). The radiaxial fibrous calcite encloses patches of matrix and isolated allochems. The RFC crystals are oriented perpendicularly to the substrate whether it is a cavity wall or enclosed allochems. This means that the RFC crystals could not grow from the centre of the cavity outward as postulated by Ross et al. (1975). There are also numerous “floating” isolated allochems, which are much smaller than the surrounding RFC crystals. The explanation involving three-dimensional interconnection of allochems seems to be unlikely. In the discussed mud-mound there is a conflict between apparently empty cavities that had to exist in the sediment and seeming “recrystallization” related to the same RFC that forms the initial void filling. The authors favor an alternative explanation of the “recrystallization”. We presume that the allochems served as nucleation points on which the crystals started to grow. Obviously, the allochems and the micritic patches were different from the surrounding material. RFC crystals (either short-or long-bladed) of the “recrystallization” spar grew at the expense of decaying microbial mucillages. The mucus can enclose peloids, allochems, or whole micritic patches that “floated” in the cavity and served as nucleation sites for the RFC crystals. The entire mud-mound represents a microbially bound autochthonous micritic mass; the stromatactis and stromatactis-like cavities originated where purer mucillage patches occurred, giving rise to open spaces. Such features as the morphological variety of stromatactis fabrics, the pervasive penetration of the sparry calcite into matrix, and the enclosure of the “floated” allochems and mudstone patches by sparry calcite, seem to provide support for the presence of mucus aggregates within the mound body. The mucus might be related to protozoans rather than to sponges or other well organized metazoan organisms.

Occurrence of the stromatactis cavities in the underlying Bajocian-Bathonian crinoidal limestones support the inference on biological origin of the stromatactis fabrics. The alternative inorganic models of stromatactis origin (e.g., internal erosion or water-escape) are hardly applicable to the sediment formed by crinoidal skeletal detritus.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Andrusov, D. (1945): Geological investigations of the inner Klippen Belt in the Western Carpathians. Part IV-Statigraphy of Dogger and Malm, Part V—Stratigraphy of the Cretaceous.-Prace St. GU,13, 1–176, Bratislava, (In Slovak).

Arp, G., Wedermeyer, U. and Reitner, J. (2001). Fluvial tufa formation in a hard-water creek (Deinschwanger Bach, Franconian Alb, Germany.—Facies,44, 1–22, Erlangen.

Aubrecht, R. (2001): New occurrences of the Krasín Breccia (Pieniny Klippen Belt, West Carpathians): indication of Middle Jurassic synsedimentary tectonics.—Acta Geol. Univ. Com.,56, 35–56, Bratislava.

Aubrecht, R. and Kozur, H. (1995):Pokornyopsis (Ostracoda) from submarine fissure fillings and cavities in the Late Jurassic of Czorsztyn Unit and the possible origin of the Recent anchialine faunas.—Neues Jb. Geol. Paläont. Abh.,196/1, 1–17, Stuttgart.

Aubrecht, R., Misik, M. and Sykora, M. (1997): Jurassic synrift sedimentation on the Czorsztyn Swell of the Pieniny Klippen Belt in Western Slovakia.—ALEWECA symp. Sept. 1997, Introduct. articles to the excursion, 53–64, Bratislava.

Bathurst, R.G.C. (1977): Ordovician Meiklejohn bioherm, Nevada.—Geol. Mag.,114, 308–311, Cambridge.

Bathurst, R.G.C. (1982): Genesis of stromatactis cavities between submarine crusts in paleozoic carbonate mud buildups.—J. geol. Soc. London,139/2, 165–181, Oxford.

Bathurst, R.G.C. (1998): The world's most spectacular carbonate mudmounds (Middle Devonian, Algerian Sahara)-discussion.—J. Sed. Res.,68/5, p. 1051, Tulsa.

Belka, Z. (1994): Devonian carbonate mud buildups of the Central Sahara and their relation to submarine hydrothermal venting.—Przegl. Geol.,42, 341–346, Warszawa (in Polish).

Belka, Z. (1998): Early Devonian kess-kess carbonate mud mounds of the eastern Anti-Atlas (Morocco), and their relation to submarine hydrothermal venting.—J. Sed. Res.,68, 368–377, Tulsa.

Bernet-Rollande, M.C., Maurin, A.F. and Monty, C.L.V. (1981): De la bactérie au réservoir carbonate.—Pétrol. et Techniq.,283, 96–98.

Birkenmajer, K. (1977): Jurassic and Cretaceous lithostratigraphic units of the Pieniny Klippen Belt, Carpathians, Poland.—Stud. Geol. Pol.,45, 1–158, Kraków.

Black, W.W. (1952): The origin of the supposed tufa bands in Carboniferous reef limestones.—Geol. Mag.,89, 195–200, Cambridge.

Bosence, D.W.J. and Bridges, P.H. (1995): A review of the origin and evolution of carbonate mud-mounds.-In: Monty, C.L.V., Bosence, D.W.J., Bridges P.H. and Pratt, B.R. (eds.): Carbonate Mud-Mounds: their origin and evolution.-IAS Spec. Publ.23, 11–48, Oxford.

Bourque, P.A. and Gignac, H. (1986): Sponge constructed stromatactis mud-mounds. Silurian of Gaspé, Québec-reply.—J. Sed. Petrol.,56/3, 461–463, Tulsa.

Bourque P.A. and Boulvain, F. (1993): A model for the origin and petrogenesis of the red stromatactis limestone of Paleozoic carbonate mounds.—J. Sed. Petrol.,63/4, 607–619, Tulsa.

Bridges, P.H. and Chapman, A.J. (1988): The anatomy of a deep water mud-mound complex to the southwest of the Dinantian platform in Derbyshire, UK.—Sedimentology,35, 139–162, Oxford.

Camoin, G. and Maurin, A.-F. (1988): Rôles des micro-organismes (bactéries, cyanobactéries) dans la genèse des “Mud Mounds”. Exemples du Turonien des Jebels Biréno et Mrhila (Tunisie).—C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris,307, Sér. II, 401–407, Paris.

Canerot, J. (2001): Cretaceous mud-mounds from the Western Pyrenees and the South-Aquitaine Basin (France). Stratigraphic and geodynamic settings; petroleum trap properties.—Géol. Méditer.,28/1–2, 33–36, Marseille.

Carozzi, A.V. and Zadnik, V.E. (1959): Microfacies of Wabash reef, Wabash, Indiana.—J. Sed. Petrol.,29, 164–171, Tulsa.

Carver, R.E. (1971), ed.): Procedures in sedimentary petrology.—1–653, New York, (Wiley).

Chafetz, H.S. (1986): Marinepeloids: a product of bacterially induced precipitation of calcite.—J. Sed. Petrol.,56, 812–817, Tulsa.

Coron, C.R. and Textoris, D.A. (1974): Non-calcarous algae in Silurian carbonate mud mound, Indiana.—J. Sed. Petrol.,44/4, 1248–1250, Tulsa.

Craig, H. (1957): Isotopic standards for carbon and oxygen and correction factors for mass spectrometric analysis of carbon dioxide.—Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta,12, 133–140, Amsterdam.

Cross, T.A. and Klosterman, M.J. (1981). Primary submarine cements and neomorphic spar in a stromatolitic-bound phylloid algal bioherm, Laborcita Formation (Wolfcampian), Sacramento Mountains, New Mexico, U.S.A.—In: Monty, C.L.V. (ed.): Phanerozoic stromatolites.-60–73, Berlin (Springer).

Desbordes, B. and Maurin, A.F. (1974): Troix exemples d'études du Frasnien de l'Alberta, Canada.—Notes Mém. Cie. Fr. Pétrol.,11, 293–336, Paris.

Dunham, R.J. (1969): Early vadose silt in Towsend mound (reef), New Mexico.—In: Friedman, G.M. (ed.): Depositional environments in carbonate rocks-a symposium.-SEPM Spec. Publ.14, 139–181, Tulsa.

Dupont, E. (1881): Sur l'origine des calcaires dévoniens de la Belgique.—Mus. Roy. Hist. Nat. Belg., Bull.,1, 264–280, Bruxelles.

Dupont, E. (1882): Les Iles coralliennes de Roly et de Phillippeville.—Bull. Acad. Roy. Belg., sér. 3,2 89–160, Bruxelles.

Flajs, G. and Hüssner, H. (1993): A microbial model for the Lower Devonian stromatactis mud mounds of the Montagne Noire (France).—Facies,29, 179–194, Erlangen.

Flajs, G., Hüssner, H. and Vigener, M. (1996): Stromatactis mud mounds in the Upper Emsian of the Montagne Noire (France): formation and diagenesis of stromatactis structures.-In: Reitner, J., Neuweiler, F. and Gunkel, F. (eds.): Global and regional controls on biogenic sedimentation. I. Reef evolution. Research reports.-Gött. Arb. Geol. Paläont., Sb2, 345–348, Göttingen.

Hammes, U. (1995): Initiation and development of small-scale sponge mud-mounds, Late Jurassic, southern Franconian Alb, Germany.-In: Monty, C.L.V., Bosence, D.W.J., Bridges P.H. and Pratt, B.R. (eds.): Carbonate Mud-Mounds: their origin and evolution.-IAS Spec. Publ.23, 335–357, Oxford.

Heckel, P.H. (1972): Possible inorganic origin for stromatactis in calcilutite mounds in the Tully Limestone, Devonian of New York.—J. Sed. Petrol.,42/1, 7–18, Tulsa.

Henning, N.G., Meyers, W.J. and Grams, J.C. (1989): Cathodoluminescence in diagenetic calcites: The roles of Fe and Mn as deduced from electron probe and spectrophotometric measurements.—J. Sed. Petrol.,59/3, 404–411, Tulsa.

Hovland, M., Talbot, M., Qvale, H., Olaussen, S. and Aasberg, L. (1987): Methane-related carbonate cements in pockmarks of the North Sea.—J. Sed. Petrol.,57, 881–892, Tulsa.

Hüssner, H., Flajs, G. and Vigener, M. (1995): Stromatactis-mud mound formation-a case study from the Lower Devonian, Montagne Noire (France).—Beitr. Paläont.,20, 113–121, Wien.

James, N.P. and Gravestock, D. (1990): Lower Cambrian shelf and shelf margin buildups, Flinders Ranges, South Australia.—Sedimentology,37, 455–480, Oxford.

Jansa, L.F., Pratt, B.R. and Dromart, G. (1989): Deep water thrombolite mounds from the Upper Jurassic of offshore Nova Scotia.-In: Geldsetzer, H.H., James, N.P. and Tebutt, G.E. (eds.): Reefs, Canada and adjacent areas.-Mem. Can. Soc. Petrol. Geol.,13, 725–735, Calgary.

Jenkyns, H.C. (1970): Growth and disintegration of carbonate platform.—N. Jahrb. Geol. Paläont., Mon.,1970, 325–344, Stuttgart.

Kauffman, E.G., Arthur, M.A., Howe, B. and Scholle, P.A. (1996): Widespread venting of methane-rich fluids in Late Cretaceous (Campanian) submarine springs (Tepee Buttes) Western Interior seaway, U.S.A.—Geology,24/9, 799–802, Boulder.

Kaufmann, B. (1997): Diagenesis of Middle Devonian carbonate mounds of the mader Basin (eastern Anti-Atlas, Morocco).—J. Sed. Res.,65, 5, 945–956, Tulsa.

Krause, F.F. (1999): Genesis of a mud-mound, Meijlejohn Peak, lime mud-mound, Bare Mountain Quadrangle, Nevada, USA.—Sedim. Geol.,145/3–4, 189–213, Amsterdam.

Kukal, Z. (1971): Open-space structures in the Devonian limestones of the Barrandian (Central Bohemia).—Cas. pro miner. a geol.,16/4, 345–362, Praha.

Kutek, J. and Wierzbowski, A. (1986): A new account on the Upper Jurassic stratigraphy and ammonites of the Czorsztyn succession, Pieniny Klippen Belt, Poland.—Acta Geol. Pol.,36/4, 289–316 Warszawa.

Lees, A. (1964): The structure and origin of the Waulsortian (Lower Carboniferous) reefs of west-central Eire.—Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., ser. B.,247, 483–531, London.

Lees, A., and Miller J. (1995): Waulsortian banks.—In: Monty, C.L.V., Bosence, D.W.J., Bridges P.H. and Pratt, B.R. (eds.): Carbonate Mud-Mounds: their origin and evolution.—IAS Spec. Publ.23, 191–271, Oxford.

Leinfelder, R.R. (1985): Cyanophyte calcification morphotypes and depositional environments (Alenquer Oncolite, Upper Kimmeridgian?, Portugal).—Facies,12, 253–274, Erlangen.

Leinfelder, R.R. and Keupp, H. (1995): Upper Jurassic mud mounds: allochthonous sedimentationversus autochthonous carbonate production.—In: Reitner, J. and Neuweiler, F., 1995: Mud mounds: recognizing a polygenetic spectrum of fine-grained carbonate buildups.—Facies,32, 17–26, Erlangen.

Logan, B.W. and Semeniuk, V. (1976). Dynamic metamorphism; processes and products in Devonian carbonate rocks, Canning Basin, Western Australia.—Geol. Soc. Australia Spec. Publ.,6, 1–138, Melbourne.

Lohmann, K.C. (1988): Geochemical patterns of meteoric diagenetic systems and their application to studies of paleokarst.—In: James, N.P. and Choquette, P.W. (eds.): Paleokarst.— 58–80, New York (Springer).

Lowenstam, H.A. (1950): Niagaran reefs of the Great Lakes area.— J. Geol.,58, 430–487, Oxford.

Mathur, A. (1975): A deeper water mud mound facies in the Alps. —J. Sed. Petrol.45/4, 787–793, Tulsa.

Matyszkiewicz, J. (1993): Genesis of stromatactis in an Upper Jurassic carbonate buildup (Mlynka, Cracow region, Southern Poland): internal reworking and erosion of organic growth vavities.—Facies,28, 87–96, Erlangen.

Matyszkiewicz, J. (1997): Stromatactis cavities and stromatactislike cavities in the Upper Jurassic carbonate buildups at Mlynka and Zabierzów (Oxfordian southern Poland).—Ann. Soc. Geol. Pol.,67/1, 45–55, Kraków.

Mazzullo, S.J., Bischoff, W.D. and Lobitzer, H. (1990): Diagenesis of radiaxial fibrous calcite in a subunconformity, shallowburial setting: Upper Triassic and Liassic, Northern Calcareous Alps, Austria.—Sedimentology,37, 407–425, Oxford.

Misik, M., 1979: Sedimentological and microfacies study in the Jurassic of the Vrsatec (castle) klippe—neptunic dykes, Oxfordian bioherm facies.—Záp. Karpaty, Sér. geol.,5, 7–56, Bratislava (in Slovak, with English summary).

Misik, M., Siblík, M., Sykora, M. and Aubrecht, R. (1994): Jurassic brachiopods and sedimentological study of the Babiná klippe near Bohunice (Czorsztyn Unit. Pieniny Klippen Belt). —Mineralia Slovaca,26/4, 255–266, Kosice.

Monty, C.L.V. (1995): The rise and nature of carbonate mudmounds: an introductory actualistic approach.—In: Monty, C.L.V. Bosence, D.W.J. Bridges P.H. and Pratt, B.R. (eds.): Carbonate Mud-Mounds: their origin and evolution. IAS Spec. Publ.23, 11–48, Oxford.

Mounji, D., Bourque, P.-A., and Savard, M.M. (1998): Hydrothermal origin of Devonian conical mounds (Kess-Kess) of Hamar Lakhdad Ridge, Anti-Atlas, Morocco.—Geology,26/12, 1123–1125, Boulder.

Myczynski, R. and Wierzbowski, A. (1994): The Ammonite Succession in the Callovian, Oxfordian and Kimmeridgian of the Czorsztyn Limestone Formation, at Halka Klippe, Pieniny Klippen Belt, Carpathians.—Bull. Pol. Acad. Sci. Earth. Sci.,42/3, 156–163, Warszawa.

Neumann, A.C., Kofoed, J.W., and Keller, G.H. (1977): Lithoherms in the Straits of Florida.—Geology,5, 4–10, Boulder.

Neuweiler, F., Bourque, P.-A. and Boulvain, F. (2001): Why is stromatactis so rare in Mesozoic carbonate mud mounds?.— Terra Nova,13/5, 338–346, Oxford.

Neuweiler, F., Gautret, P., Thiel, V., Langes, R., Michaelis, W., and Reitner, J. (1999): Petrology of Lower Cretaceous carbonate mud mounds (Albian, N. Spain): insights into organomineralic deposits of the geological record.—Sedimentology,46, 837–859, Oxford.

Orme, G.R. and Brown, W.W.M. (1963): Diagenetic fabrics in the Avonian Limestones of Derbyshire and North Wales.—Proc. Yorkshire Geol. Soc.,34/1–3, 51–66 York.

Otte, C. Jr. and Parks, J.M., Jr., 1963: Fabric studies of Virgial and Wolfcamp bioherms, New Mexico.—J. Geol.,71, 380–396, Chicago.

Pascal, A. and Przybyla, A. (1989): Processus, biosédimentaires et diagénétiques précoces dans les mud-mounds (Thrombolite-mounds) urgoniens d''spagne du Nord (Aptien-Albien) et leus signification.—Géol. Méditer.,16/2–3, 171–183, Marseille.

Pevny, J. (1969). Middle Jurassic brachiopods in the Klippen Belt of the central Váh Valley.—Geol. práce, Správy,50, 133–160, Bratislava (in Slovak with English summarry).

Philcox, M.E. (1963): Banded calcite mudstone in the Lower Carboniferous “reef” knolls of the Dublin Basin, Ireland.—J. Sed. Petrol.,33/4, 904–913, Tulsa.

Pratt, B.R. (1982): Stromatolitic framework of carbonate mudmounds. —J. Sed. Petrol.,52/4, 1203–1227, Tulsa.

Pratt, B.R. (1986): Sponge constructed stromatactis mud-mounds. Silurian of Gaspé, Québec-discussion.—J. Sed. Petrol..,56/3, 459–460, Tulsa.

Pratt, B.R. (1995): The origin, biota and evolution of deep-water mud-mounds.—In: Monty, C.L.V., Bosence, D.W.J., Bridges P.H. and Pratt, B.R. (eds.): Carbonate Mud-Mounds: their origin and evolution.—IAS Spec. Publ.23, 49–123, Oxford.

Rakús, M., 1990: Ammonites and stratigraphy of Czorsztyn Limestones base in Klippen Belt of Slovakia and Ukrainian Carpathians.—Knih. Zem. plynu a nafty,9b, 73–108, Hodonín (in Slovak with English summary).

Reitner, J., Neuweiler, F. and Gautret P. (1995): Modern and fossil automicrites: implications for mud mound genesis—In: Reitner, J. and Neuweiler, F. (eds.): Mud Mounds: A Polygenetic Spectrum of Fine-grained Carbonate Buildups.—Facies,32, 4–17, Erlangen.

Ross, R.J., Jr., Jaanusson, V. and Friedman, I. (1975): Lithology and origin of Middle Ordovician calcareous mudmounds at Meiklejohn Peak southern Nevada.—U.S. Geol. Surv. Prof. Paper,871, 1–48, Washington.

Schmid, D.U., Leinfelder, R.R. and Nose, M. (2001): Growth dynamics and ecology of Upper Jurassic mounds, with comparisons to Mid-Palaeozoic mounds.—Sedim. Geol.,145/3–4, 343–376, Amsterdam.

Schwarzacher, W. (1961): Petrology and structure of some Lower Carboniferous reefs in northwestern Ireland.—AAPG Bull.,46, 1481–1503, Tulsa.

Shinn, E.A. (1968): Burrowing in Recent lime sediments of Florida and the Bahamas.—J. Paleont.,42/4, 879–894.

Textoris, D.A. (1966): Algal cap for a Niagaran (Silurian) carbonate mud mound of Indiana.—J. Sed. Petrol.,36/2, 455–461, Menasha.

Textoris, D.A. and Carozzi, A.V. (1964): Petrography and evolution of Niagaran (Silurian) reefs, Indiana.—AAPG Bull.,48, 397–426, Tulsa.

Tsien, H.H. (1985a): Origin of Stromatactis-a replacement of colonial microbial accretion.—In: Toomey, D.F., and Nitecki, M.H. (eds.): Paleoalgology.—274–289, Berlin (Springer).

Tsien, H.H., (1985b): Algal-bacterial origin of micrites in mud mounds.—In: Toomey, D.F. and Nitecki, M.H. (eds.): Paleoalgology.—290–2296, Berlin (Springer).

Wallace, M.W. (1987): The role of internal erosion and sedimentation in the formation of stromatactis mudstones and associated lithologies.—J. Sed. Petrol.,57, 4, 695–700, Tulsa.

Wendt, J., Belka, Z., Kaufmann, B., Kostrewa, R., and Hayer, J. (1997): The world's most spectacular carbonate mud mounds (Middle Devonian, Algerian Sahara).—J. Sed. Petrol,68/5, 1051–1052, Tulsa.

Wendt, J. et al. (1998): The world's most spectacular carbonate mud mounds (Middle Devonian, Algerian Sahara)-reply.—J. Sed. Res.,68/5, 1051–1052, Tulsa.

Wetzel, A. and Allia, V. (2000): The significance of hiathus beds in shallow-water mudstones: an example from the Middle Jurassic of Switzerland.—J. Sed. Res.,70/1, 170–180, Tulsa.

Wierzbowski, A. Jaworska, M. and Krobicki, M. (1999): Jurassic (Upper Bajocian-Lowest Oxfordian) ammonitico rosso facies in the Pieniny Klippen Belt. Carpathians, Poland: its fauna, age, microfacies and sedimentary environment.—Stud. Geol. Pol.,115, 7–74, Kraków.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aubrecht, R., Szulc, J., Michalik, J. et al. Middle Jurassic stromatactis mud-mound in the Pieniny Klippen Belt (Western Carpathians). Facies 47, 113–126 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02667709

Received:

Revised:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02667709