Summary

The experimental results ofGeyer-Duszynska (1959), speaking in favour of three ooplasmic factors localized in the pole plasm, in the basophilic oosome material contained therein, as well as in the periplasm of the posterior egg pole ofWachtliella persicariae, suggested to investigate for further factor regions with other technical means. Since ooplasmic factor regions may be indicated by initial regions of morphogenetic development, kinematics were used for in vivo analysis of early embryonic development by means of time-lapse motion pictures. Electron microscopic investigations added to the micro-morphological aspects of plasmic systems within the egg for a better understanding of nature and effectivity of ooplasmic factors.

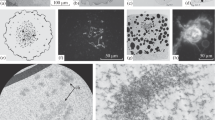

Cleavage nuclei do not move exclusively by means of their spindle activity during anaphase movement. The nuclear envelope of cleavage energides consists of either two unit membranes with pores or of many tube-like as well as membranous elements. The appearence of a complex multi-layered nuclear envelope coincides with the moving phase of energides, an observation which is discussed in relation to the possibility of active nuclear movement. During late preblastoderm the entoplasm contains horse-shoe-shaped and multilobed vitellophagues with dense karyoplasm. With the blastoderm formed, the nuclei may become pycnotic, their membranes fragmenting at the same time. These fragments probably are piled up to form annulated membranes.

The pole plasm does not show specific structures apart from the oosome material, contained therein. It is free of yolk material and nearly exclusively consists of ground plasm. The basophilic oosome material within the pole plasm is not surrounded by any membranes. It consists of numerous ribosome-like units and is restricted to the plasm of the future pole cells. The micro structure of the oosome material is preserved at least till the germ band has reached its maximal length.

The cell membranes develop by invagination of the oolemma which penetrates into the egg interior. While pole cells and blastoderm cells become tied off, the ground plasm possibly participates in the growing-in process of the cell membranes by developing fibrous differentiations at the terminal extensions of oolemma folds.

There is no clear cut limitation between periplasm and entoplasm. The periplasm which is without yolk material, appears rich in ground plasm and does not contain specific ultra structures. During the process of cleavage external ooplasmic regions of the egg are shifted in rhythmical pulsation parallel to its longer axis by a maximum of about 6 % of the entire egg length. Topographic statements of certain areas concerning any anlage therefore are bound to suffer from an adequate lack of exactness. Since comparable shifting processes within the egg plasm probably are common in insects other thanWachtliella, they should be considered as a certain source of error.

At 60+−3 % of egg length as measured from its posterior pole, there exists a cleavage centre, an initial region of intravitelline cleavage and of repeated mitotic waves. Adjacent to the middle of the egg follows an initial region of germ band formation (differentiation centre). By their electron microscopic appearance, both developmental centres are not characterized by specific ultra structures. The factor region at the posterior pole exclusively represents an initial region of cell wall formation during superficial cleavage.

Other than any experimental marking procedure the technique of time-lapse motion pictures permits to evaluate quantitatively and without artificial interfering the shifting of presumptive segment material during morphogenetic movements of the germ band. The embryonic material of the blastoderm at the egg equator is used for building up the first abdominal segment. The prothoracal and mesothoracal material at about 60% of the egg length stays in site when the germ band becomes extended lengthwise. Closely behind the differentiation centre there is a region of maximal extension as well as of shortening of the germ band. No proliferous growth of segments (segment formation zone) has been found.

Zusammenfassung

-

1.

Die aus den ExperimentenGeyer-Duszynskas (1959) gefolgerte Existenz dreier plasmatischer Faktoren, die im Polplasma, im darin eingelagerten basophilen Oosommaterial und im Periplasma am Hinterpol des Eies vonWachtliella persicariae liegen, hat den Anstoß gegeben, nach weiteren Faktorenbereichen zu suchen. Die Initialbereiche morphogenetischer Prozesse können Indikatoren für ooplasmatische Faktorenbereiche sein. Deshalb ist die Kinematik der frühen Embryonalentwick-lung anhand von Zeitraffer-Filmaufnahmenin vivo analysiert worden. Elektronenoptische Untersuchungen fügen ergänzend den mikromorphologischen Aspekt ooplasmatischer Teilsysteme hinzu mit dem Ziel, Aussagen über Natur und Wirkungsweise plasmatischer Faktoren machen zu können.

-

2.

Die Furchungskerne werden nicht allein mit Hilfe ihrer Spindel bewegt. Die Kernhülle der Furchungsenergiden besteht entweder aus zwei porentragenden Elementarmembranen oder aber aus einer Vielzahl tubulärer und membranöser Elemente. Das Auftreten der vielschichtig-komplexen Kernwand fällt in die Wanderphase der Energiden und wird im Zusammenhang mit der Möglichkeit einer aktiven Kernwanderung diskutiert.

-

3.

Das Polplasma zeichnet sich, von den Oosompartikeln abgesehen, nicht durch spezifische Feinstrukturen aus. Es ist dotterfrei und besteht fast ausschließlich aus Grundplasma.

-

4.

Das basophile Oosommaterial liegt frei im Polplasma am Hinterpol des Eies. Es besteht aus zahlreichen ribosomenähnlichen Einheiten und wird auf das Plasma der künftigen Polzellen beschränkt. Sein Feinbau bleibt mindestens bis zum Stadium des maximal langen Keimstreifs erhalten.

-

5.

Die Zellwände entstehen aus Einstülpungen des Oolemmas, die in das Ei-Innere vordringen. Bei der Abschnürung von Pol- und Blastodermzellen ist das Grundplasma möglicherweise aktiv am Einwachsen der Zellwände beteiligt, und zwar durch die Ausbildung fädiger Differenzierungen an den terminalen Erweiterungen der Oolemmafalten.

-

6.

Das dotterfreie Periplasma ist nicht deutlich vom Entoplasma abgegrenzt. Es ist reich an Grundplasma und zeichnet sich in keinem Stadium durch spezifische Feinstrukturen aus.

-

7.

BeiWachtliella verschieben sich äußere Ooplasmabereiche während der Furchung um maximal +−6% der gesamten Eilänge pulsierend parallel zur Längsachse. Bei topographischen Angaben bestimmter Anlagebereiche muß daher mit einer entsprechenden Ungenauigkeit gerechnet werden. Ähnliche Plasmaverlagerungen sind auch in den Eiern anderer Insekten zu erwarten und gegebenenfalls als Fehlerquelle zu berücksichtigen.

-

8.

Zur Zeit des späten Präblastoderms treten im Entoplasma hufeisenförmige sowie vielgelappte Dotterkerne mit dichtem Karyoplasma auf. Im Anschluß an die Blastodermbildung werden sie pyknotisch, und die Kernwand fragmentiert. Die Bruckstücke treten vermutlich zu Stapeln von annulated membranes zusammen.

-

9.

Ein Furchungszentrum, Initialbereich der intravitellinen Furchung und Ausgangspunkt der folgenden Mitosewellen, liegt bei 60 +−3 % der Eilänge. Dicht hinter der Eimitte liegt ein Initialbereich für die Bildung des Keimstreifs (Differenzierungszentrum). Beide Entwicklungszentren zeichnen sich elektronenoptisch nicht durch spezifische Feinstrukturen aus. Der Faktorenbereich am Hinterpol ist nur Initialbereich für die Zellwandbildung bei der superfiziellen Furchung.

-

10.

Die Zeitraffertechnik ermöglicht es, im Gegensatz zu experimentellen Markierungsverfahren, ohne äußere Eingriffe die Verlagerung des präsumptiven Segmentmaterials während der Gestaltungsbewegungen des Keimstreifs quantitativ auszuwerten. Das embryonale Blastodermmaterial am Äquator des Eies wird für das erste Abdomensegment verwendet. Das Material für Pro- und Meso-Thorax bei ca. 60% der Eilänge bleibt während der Streckung des Keimstreifs am Ort liegen. Dicht hinter dem Differenzierungszentrum liegt ein Intensitätsmaximum der Streckung wie auch der Verkürzung des Keimstreifs. Eine Segmentbildungszone ist nicht vorhanden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literatur

Afzelius, B. A.: The ultrastructure of the nuclear membrane of the sea-urchin oocyte as studied with the electron microscope. Exp. Cell Res.8, 147–158 (1955).

—: Electron microscopy on the basophilic structures of the sea-urchin egg. Z. Zellforsch.45, 660–675 (1957).

Bantock, C.: Chromosome elimination in Cecidomyiidae. Nature (Lond.)190, 466 (1961).

—: Nucleo-cytoplasmic relationships in differentiation: Studies on the development ofMayetiola destructor. D. Phil. Thesis, Bodleian Library, Oxford (1964).

Barnicot, N. A., andH. E. Huxley: Electron microscope observations on mitotic chromosomes. Quart. J. micr. Sci.106, pt 3, 197–214 (1965).

Bhownick, D. K., u.K. E. Wohlfarth-Bottermann: An improved method for fixing amoeba for electron microscopy. Exp. Cell Res.40, 252–263 (1965).

Counce, S. J.: The analysis of insect embryogenesis. Ann. Rev. Entomology6, 295–312 (1961).

Danneel, S., u.N. Weissenfels: Ein besseres Fixierungsverfahren zur Darstellung des Grundplasmas von Protozoen und Vertebratenzellen. Mikroskopie20, 89–93 (1965).

Davis, C. W. C., J. Krause, andG. Krause: Morphogenetic movements and segmentation of posterior egg fragmentsin vitro (Calliphora erythrocephala Meig., Diptera). Wilhelm Roux' Archiv161, 209–240 (1968).

Geyer-Duszynska, I.: A quick cytological method for mounting embryos of some insects. Zoologica Polon.7, 411–421 (1956).

—: Experimental research on chromosome elimination in Cecidomyiidae (Diptera). J. exp. Zool.141, 391–448 (1959).

—: Spindle disappearance and chromosome behaviour after partial-embryo irradiation in Cecidomyiidae. Chromosoma (Berl.)12, 391–441 (1961).

—: Genetic factors in oogenesis and spermatogenesis in Cecidomyiidae. Chromosomes Today1, 174–178 (1966).

Gurdon, J. B., andH. R. Woodland: The cytoplasmic control of nuclear activity in animal development. Biol. Rev.43, 223–267 (1968).

Harrison, G. A.: Some observations on the presence of annulate lamellae in Alligator and Sea Gull adrenal cortical cells. J. Ultrastruct. Res.14, 158–166 (1966).

Hayward, A. F.: Electron microscopy of inducted pinocytosis inAmoeba proteus. C. R. Lab. Carlsberg33, 535–558 (1961).

Hegner, R. W.: The effects of removing the germ cell determinants from the eggs of some Chrysomelid beetles. Biol. Bull.16, 19 (1908).

—: The effects of centrifugal force upon the eggs of some Chrysomelid beetles. J. exp. Zool.6, 507 (1909).

—: Experiments with Chrysomelid beetles. III. The effects of killing parts of the eggs ofLeptinotarsa decemlineata. Biol. Bull.20, 237 (1911).

Idris, B. E. M.: Die Entwicklung im normalen Ei vonCulex pipiens L. (Diptera). Z. Morph. Ökol. Tiere49, 387–429 (1960).

—: Die Entwicklung im geschnürten Ei vonCulex pipiens L. (Diptera). Wilhelm Roux' Arch. Entwickl.-Mech. Org.152, 230–262 (1960).

Karasaki, S.: Electron microscope studies on the cytoplasmic structures of the ectoderm cells ofTriturus embryo during the early phase of differentiation. Embryologia4, 247–272 (1959).

Karnovsky, M. J.: Simple methods for “staining with lead” at high pH in electron microscopy. J. biophys. biochem. Cytol.11, 729 (1961).

Kessel, R. G.: Some observations on the ultrastructure of the oocyte ofThyone briareus with special reference to the relationship of the Golgi complex and the endoplasmic reticulum in the formation of yolk. J. Ultrastruct. Res.16, 305–319 (1966).

King, R. C.: Oogenesis in adultDrosophila melanogaster. IX. Studies on the cytochemistry and ultrastructure of developing oocytes. Growth24, 265–323 (1960).

Komnick, H., u.K. E. Wohlfarth-Bottermann: Das Grundplasma und die Plasmafilamente der AmöbeChaos chaos nach enzymatischer Behandlung der Zellmembran. Z. Zellforsch.66, 434–456 (1965).

Koulish, S.: Ultrastructure of differentiation oocytes in the trematodeGorgoderina attenuata. I. The “nucleolus-like” body and some lamellar membrane systems. Develop. Biol.12, 248–268 (1965).

Krause, G.: Einzelbeobachtungen und typische Gesamtbilder der Entwicklung von Blastoderm und Keimanlage im Ei der GewächshausheuschreckeTachycines asynamorus Adelung. Z. Morph. Ökol. Tiere34, 1–78 (1938a).

—: Die Eitypen der Insekten. Biol. Zbl.59, 495–536 (1939a).

—, u.J. Krause: Die Regulation der Embryonalanlagen vonTachycines im Schnittversuch. Zool. Jb., Abt. Anat. u. Ontog.75, 481–550 (1957).

Krause, G.: Neue Beiträge zur Entwicklungsphysiologie des Insektenkeimes. Verh. Dtsch. Zool. Ges. 1957, 396–424 (1958b).

— Preformed ooplasmic reaction systems in insect eggs. Sympos. on germ cells and development, 302–337. Inst. Internat. d'Embryol. and Fondazione A. Baselli (1960).

—, andK. Sander: Ooplasmic reaction systems in insect embryogenesis. Advanc. Morphogenes.2, 259–303 (1962).

Mahowald, A. P.: Fine structure of pole cells and polar granules inDrosophila melanogaster. J. exp. Zool.151, 201–216 (1962).

—: Electron microscopy of the formation of the cellular blastoderm inDrosophila melanogaster. Exp. Cell Res.32, 457–468 (1963a).

—: Ultrastructural differentiations during formation of the blastoderm in theDrosophila melanogaster embryo. Develop. Biol.8, 186–204 (1963b).

—: Fine structure of polar granules inMiastor, J. Cell Biol.39, Nr. 2, p. 84 (1968).

Meng, C.: Strukturwandel und histochemische Befunde insbesondere des Oosoms während der Oogenese und nach der Ablage des Eies vonPimpla turionellae L. (Hymenoptera, Ichneumouidea). Wilhelm Roux' Archiv161, 162–208 (1968).

Metz, C. W.: Interaction between chromosomes and cytoplasm during early embryonic development inSciara (Diptera). Biol. Bull.113, 323 (1957).

Meyer, G. P.: The fine structure of spermatocyte nuclei ofDrosophila melanogaster. Proc. Eur. Conf. on Electron Microscopy, vol. II, Delft 1960.

Nicklas, R. B.: An experimental and descriptive study of chromosome elimination inMiastor spec. (Cecidomyiidae, Diptera). Chromosoma (Berl.)10, 301–336 (1959).

—: The chromosome cycle of a primitive Cecidomyiid —Mycophila speyeri. Chromosoma (Berl.)11, 402–418 (1960).

Oelhafen, F.: Zur Embryogenesis vonCulex pipiens: Markierungen und Extirpationen mit UV-Strahlen-Stich. Wilhelm Roux' Arch. Entwickl.-Mech. Org.153, 120–157 (1961).

Okada, E., andC. H. Waddington: The submicroscopic structure of theDrosophila egg. J. Embryol. exp. Morph.7, 583–597 (1959).

Reynolds, E. S.: The use of lead citrate at high pH as an electronopaque stain in electronmicroscopy. J. Cell Biol.17, 208 (1963).

Ruthmann, A.: Methoden der Zellforschung. Stuttgart: Kosmos, Franckh'sche Verlagshandlung 1966.

Schanz, G.: Entwicklungsvorgänge im Ei der LibelleIschnura elegans und Experimente zur Frage ihrer Aktivierung. Eine Mikro-Zeitraffer-Film-Analyse. Inaug.-Diss. Marburg/Lahn 1965.

Schnetter, M.: Morphologische Untersuchungen über das Differenzierungszentrum in der Embryonalentwicklung der Honigbiene. Z. Morph. Ökol. Tiere29, 114–195 (1934a).

Seidel, F.: Die Geschlechtsorgane in der embryonalen Entwicklung vonPyrrhocoris apterus. Z. Morph. Ökol. Tiere1, 429–506 (1924).

—: Untersuchungen über das Bildungsprinzip der Keimanlage im Ei der LibellePlatycnemis pennipes. Wilhelm Roux' Arch. Entwickl.-Mech. Org.119, 322–440 (1929).

—: Entwicklungsphysiologie der Tiere I, II. Göschenband 1162, 1163. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter 1953.

— Entwicklungsphysiologische Zentren im Eisystem der Insekten. Verh. Dtsch. Zool. Ges. Bonn, 121–142 (1960).

— Das Eisystem der Insekten und die Dynamik seiner Aktivierung. Verh. Dtsch. Zool. Ges. in Jena, 166–187 (1966).

Silvestri, F.: Prime fasi di Sviluppo delCopidosoma buyssoni, Imenottero Chalcidide. Anat. Anz.47, 45–56 (1914).

Swift, H.: The fine structure of annulate lamellae. J. biophys. biochem. Cytol.2, Suppl. 415–418 (1956).

Ullmann, S. L.: Epsilon granules inDrosophila pole cells and oocytes. J. Embryol. exp. Morph.13, 73–81 (1965).

Waddington, C. H., andE. Okada: Some degenerative phenomena inDrosophila ovaries. J. Embryol. exp. Morph.8, 341–348 (1960).

Weissenfels, N., u.S. Danneel: Nachkontrastierung elektronenmikroskopischer Präparate im Vestopalblock. Mikroskopie20, 80–84 (1965).

Wohlfarth-Bottermann, K. E.: Die Kontrastierung tierischer Zellen und Gewebe im Rahmen ihrer elektronenmikroskopischen Untersuchung an ultradünnen Schnitten. Naturwissenschaften44, 287 (1957).

—: Cell structures and their significance for ameboid movement. Int. Rev. Cytol.16, 61–131 (1964a).

Wolf, R.: Der Feinbau des Oosoms normaler und zentrifugierter Eier der GallmückeWachtliella persicariae L. (Diptera). Wilhelm Roux' Arch. Entwickl.-Mech. Org.158, 459–462 (1967).

— Kinematik und Feinstruktur plasmatischer Faktorenbereiche des Eies vonWachtliella persicariae L. (Diptera). II. Teil: Das Verhalten ooplasmatischer Teilsysteme nach Zentrifugierung im 4-Kern-Stadium. Wilhelm Roux' Archiv (im Druck).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Meinem verehrten Lehrer, Herrn Prof. Dr. G.Krause, danke ich herzlich für die Anregung zu dieser Untersuchung, seine freundliche Förderung und Beratung und Herrn Dozenten Dr. L.Schneider für seine stete Hilfsbereitschaft, besonders in Fragen der elektronenmikroskopischen Technik. Ebenso gilt mein Dank Herrn Dozenten Dr. W.Thoenes für die Einführung in die Präparationsmethoden sowie Herrn Dr. H.-J.Reinig für wertvolle Ratschläge zum Bau der Apparatur für Zeitraffer-Aufnahmen. Ein Elektronenmikroskop der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft und andere Leihgaben standen mir zur Mitbenützung zur Verfügung.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wolf, R. Kinematik und Feinstruktur plasmatischer Faktorenbereiche des Eies vonWachtliella persicariae L. (Diptera). W. Roux' Archiv f. Entwicklungsmechanik 162, 121–160 (1969). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00573537

Received:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00573537