Summary

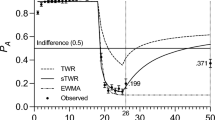

Since the process of natural selection entails a comparison of phenotypes and choosing of the best, optimality theory appears appropriate to identify selection pressures. Optimality theory doesnot test whether an organism is designed optimally — it assumes it. The ingredients of a complete optimization model are outlined and two approaches are exemplified. Both time-energy-budgeting and Pontryagin's maximum principle lead to semi-quantitative predictions about, e.g., an animal's behavior; they merely entail an inequality formalism. A discrepancy between prediction and test would not yet show a behavior to be maladaptive since several other explanations are possible. Animals optimize their behavior over intervals ranging from less than a second to months or years. It is unknown whether, with a long interval, the animal makes use of the opportunity to revise its decision(s). Present optimal foraging models predicting, e.g., diet breadth are too simple in that foragers a) may not always maximize energy intake, as postulated, b) have to allow for nutrient, toxin and remedial content of food items, and/or c) have to allow for interaction of items, annihilating their ranking along a unidimensional scale of profitability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Refences

Altmann, S.A., Avian mobbing behavior and predator recognition. Condor58 (1956) 241–253.

Askenmo, C., Reproductive effort and return rate of male pied flycatchers. Am. Nat.114 (1979) 748–752.

Barash, D.P., The influence of reproductive status on foraging by hoary marmots (Marmota caligata) Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol.7 (1980) 201–205.

Barnard, C.J., and Brown, C.A.J., Prey size selection and competition in the common shrew (Sorex araneus L.). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol.8 (1981) 239–243.

Belovsky, G.E., Diet optimization in a generalist herbivore: the moose. Theor. Pop. Biol.14 (1978) 105–134.

Brockhusen, F.v., Untersuchungen zur individuellen Variabilität der Beuteannahme vonAnolis lineatopus (Rept., Iguanidae). Z. Tierpsychol.44 (1977) 13–24.

Bryant, D.M., Reproductive costs in the house martin (Delichon urbica). J. Anim. Ecol.48 (1979) 655–675.

Caraco, T., Time budgeting and group size: A theory. Ecology60 (1979) 611–617.

Caraco, T., Time budgeting and group size: A test of theory. Ecology60 (1979) 618–627.

Caraco, T., Martindale, S., and Pulliam, H.R., Avian flocking in the presence of a predator. Nature285 (1980) 400–401.

Caraco, T., Martindale, S., and Whittam, T.S., An empirical demonstration of risk-sensitive foraging preferences. Anim. Behav.28 (1980) 820–830.

Curio, E., Experimentelle Untersuchungen zur Öko-Ethologie von Räuber-Beute-Beziehungen. Verh. dt. zool. Ges. (1975) 81–89.

Curio, E., The ethology of predation Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg/New York 1976.

Curio, E., Why do young birds reproduce less well? Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg/New York, in press.

De Steven, D., Clutch size, breeding success, and parental survival in the tree swallow (Iridoprocne bicolor). Evolution34 (1980) 278–291.

Evans, L.T., A motion picture study of maternal behavior of the lizardEumeces obsoletus Baird and Girard. Copeia (1959) 103–110.

Freed, A.N., Prey selection and feeding behavior of the green treefrog (Hyla cinerea) Ecology61 (1980) 461–465.

Gill, F.B., and Wolf, L.L., Economics of feeding territoriality in the golden-winged sunbird. Ecology56 (1975) 333–345.

Gittelmann, S.H., Optimum diet and body size in backswimmers (Heteroptera: Notonectidae, Pleidae). Ann. ent. Soc. Am.71 (1978) 737–747.

Goss-Custard, J.D., Optimal foraging and the size selection of worms by redshank,Tringa totanus, in the field. Anim. Behav.25 (1977) 10–29.

Hettrich, W., Nahrungsspektrum und Körperwachstum juvenilerAnolis lineatopus (Rept. Iguanidae). Thesis, Ruhr-University, Bochum 1981.

Hughes, R.N., Optimal diets under the energy maximization premise: the effects of recognition time and learning. Am. Nat.113 (1979) 209–221.

Jaeger, R.G., and Barnard, D.E., Foraging tactics of a terrestrial salamander: choice of diet in structurally simple environments. Am. Nat.117 (1981) 639–664.

Jennings, T., and Evans, S.M., Influence of position in flock and flock size on vigilance in the starling,Sturnus vulgaris. Anim. Behav.28 (1980) 634–635.

Kenward, R.E., Hawks and doves: factors affecting success and selection in goshawk attacks on woodpigeons. J. Anim. Ecol.47 (1978) 449–460.

Krebs, J.R., Erichsen, J.T., Webber, M.J., and Charnov, E.L., Optimal prey selection in the great tit (Parus major). Anim. Behav.25 (1977) 30–38.

Krebs, J.R., Optimal foraging: Decision, rules for predators; in: Behavioural Ecology, pp. 23–63. Eds J.R. Krebs and N.B. Davies. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Osney Mead/Oxford/London/Edinburgh/North Balwyn, 1978.

Krebs, J.R., and Davies, N.B., An introduction to behavioural ecology. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford/London/Edinburgh/Boston/Melbourne 1981.

Levins, R., Theory of fitness in a heterogeneous environment. I. The fitness set and adaptive function. Am. Nat.96 (1962) 361–373.

Levins, R., Evolution in changing environments. Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, N.Y., 1968.

Lewontin, R.C., The genetic basis of evolutionary change. Columbia Univ. Press, New York 1974.

Lipetz, V.E., and Bekoff, M., Group size and vigilance in pronghorns. Z. Tierpsychol.58 (1982) 203–216.

Maynard Smith, J., and Price, G.R., The logic of animal conflict. Nature246 (1973) 15–18.

Maynard Smith, J., Optimization theory in evolution. A. Rev. Ecol. Syst.9 (1978) 31–56.

Maynard Smith, J., Game theory and the evolution of behavior. Proc. R. Soc. London B205 (1979) 475–488.

McCleery, R.H., Optimal behavior sequences and decision making; in: Behavioural ecology, pp. 377–410. Eds. J.R. Krebs and N.B. Davies. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Osney Mead/Oxford/London/Edinburgh/North Balwyn 1978.

McNair, J.N., A generalized model of optimal diets. Theor. Popul. Biol.15 (1979) 159–170.

Milinski, M., Do all members of a swarm suffer the same predation? Z. Tierpsychol.45 (1977) 373–388.

Milinski, M., Experiments on the selection by predators against spatial oddity of their prey. Z. Tierpsychol.43 (1977) 311–325.

Milinski, M., and Heller, R., Influence of a predator on the optimal foraging behaviour of sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus L.). Nature275 (1978) 642–644.

Milinski, M., and Löwenstein, C., On predator selection against abnormalities of movement—a test of a hypothesis. Z. Tierpsychol.53 (1980) 325–340.

Milton, K., Factors influencing leaf choice by howler monkeys: a test of some hypotheses of food selection by generalist herbivores. Am. Nat.114 (1979) 362–378.

Neill, S.R.St.J., and Cullen, J.M., Experiments on whether schooling by their prey affects the hunting behaviour of cephalopod and fish predators. J. Zool., Lond.172 (1974) 549–569.

Ohguchi, O., Experiments on the selection against colour oddity of water fleas by three-spined sticklebacks. Z. Tierpsychol.47 (1978) 254–267.

Ohguchi, O., Prey density and selection against oddity by three-spined sticklebacks. Advances in Ethology, Suppl.23. 1981.

Orians, G.H., Some adaptations of marsh-nesting blackbirds. Monographs in population biology, vol. 14. Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton 1980.

Oster, G.F., and Wilson, E.O., Caste and ecology in the social insects. Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, N.J., 1979.

Partridge, L., and Maclean, R., Effects of nutrition and peripheral stimuli on preferences for familiar foods in the bank vole. Anim. Behav.29 (1981) 217–220.

Price, P.W., Evolutionary biology of parasites. Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton 1980.

Pulliam, H.R., Diet optimization with nutrient constraints. Am. Nat.109 (1975) 765–768.

Pulliam, H.R., The principle of optimal behavior and the theory of communities; in: Perspectives in Ethology, vol. 2, pp. 311–332. Eds. P.P.G. Bateson and P.H. Klopfer. Plenum Press, New York/London 1976.

Pulliam, H.R., Do chipping sparrows forage optimally? Ardea68 (1980) 75–82.

Pyke, G.H., Pulliam, H.R., and Charnov, E.L., Optimal foraging: A selective review of theory, and tests. Q. Rev. Biol.52 (1977) 137–154.

Rapport, D.J., Optimal foraging for complementary resources. Am. Nat.116 (1980) 324–346.

Schluter, D., Does the theory of optimal diets apply in complex environments? Am. Nat.118 (1981) 139–147.

Sibly, R., and McFarland, D., On the fitness of behavior sequences. Am. Nat.110 (1976) 601–617.

Stephen, D.W., The logic of risk-sensitive foraging preferences. Anim. Behav.29 (1981) 628–629.

Völkel, P., and Zell, R.A., Beobachtungen und Versuche zum Mischschwarm- und Feindverhalten einiger neotropischer Singvögel. Thesis, Ruhr-University, Bochum 1980.

Werner, E.E., and Hall, D.J., Optimal foraging and the size selection of prey by the bluegill sunfish (Lepomis macrochirus). Ecology55 (1974) 1042–1052.

Westoby, M., What are the biological bases of varied diets? Am. Nat.112 (1978) 627–631.

Whitford, W.G., and Bryant, M., Behavior of a predator and its prey: the horned lizard (Phrynosoma cornutum) and harvester ants (Pogonomyrmex spp.). Ecology60 (1979) 686–694.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Extended version of a paper delivered in the Plenary session of the XVIIth Int. Ethological Conference, Oxford 1981.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Curio, E. Time-energy budgets and optimization. Experientia 39, 25–34 (1983). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01960617

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01960617