Abstract

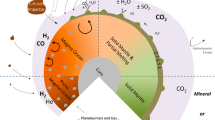

NASA and ESA have outlined visions for solar system exploration that will include a series of lunar robotic precursor missions to prepare for, and support a human return to the Moon, and future human exploration of Mars and other destinations, including possibly asteroids. One of the guiding principles for exploration is to pursue compelling scientific questions about the origin and evolution of life. The search for life on objects such as Mars will require careful operations, and that all systems be sufficiently cleaned and sterilized prior to launch to ensure that the scientific integrity of extraterrestrial samples is not jeopardized by terrestrial organic contamination. Under the Committee on Space Research’s (COSPAR’s) current planetary protection policy for the Moon, no sterilization procedures are required for outbound lunar spacecraft, nor is there a different planetary protection category for human missions, although preliminary COSPAR policy guidelines for human missions to Mars have been developed. Future in situ investigations of a variety of locations on the Moon by highly sensitive instruments designed to search for biologically derived organic compounds would help assess the contamination of the Moon by lunar spacecraft. These studies could also provide valuable “ground truth” data for Mars sample return missions and help define planetary protection requirements for future Mars bound spacecraft carrying life detection experiments. In addition, studies of the impact of terrestrial contamination of the lunar surface by the Apollo astronauts could provide valuable data to help refine future Mars surface exploration plans for a human mission to Mars.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) of the International Council for Science (ICSU) was established in 1958 to promote international level scientific research in space. One of the continuing tasks of COSPAR has been to address planetary protection issues related to the Moon, Mars, and other planetary bodies. The current COSPAR planetary protection policy states that space exploration should be conducted so as to avoid forward biological contamination of planetary bodies by outbound spacecraft that could jeopardize the search for extraterrestrial life (DeVincenzi et al. 1983; Rummel et al. 2002). The current planetary protection policy for the Moon (COSPAR 2008) related to forward contamination is not stringent (Category II; documentation only) since the probability that terrestrial life can grow in the harsh environment on the lunar surface is very low. Even survival on the lunar surface is difficult to imagine with the Moon’s nearly nonexistent atmosphere, intense ultraviolet (UV), galactic and solar cosmic radiation, lack of liquid water, and large diurnal temperature extremes ranging from −173 to +123°C at the equatorial regions and less than −230°C in permanently shadowed polar craters (Heiken et al. 1991). Sagan (1960) calculated that only a very small fraction of viable microorganisms deposited by an impacting probe would survive the harsh conditions on the lunar surface with a density of less than 10−2 m−2. Nevertheless, a wide variety of spacecraft hardware have landed or crashed on the lunar surface since 1959 (see Table 1), most of which were not sterilized delivering both biological and organic contaminants to the regolith that could be dispersed across the surface of the Moon.

Experiments carried out on NASA’s Long Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF) have shown that even after 6 years in space, a large fraction of spore forming bacteria will survive if they are not directly exposed to solar UV radiation (Horneck et al. 1994). These results demonstrated that spores can survive the low vacuum environment of space and could be delivered to the surface of the Moon by robotic spacecraft. Although bacterial growth on the Moon remains unlikely, survival of terrestrial bacteria on non-UV exposed regions, such as the interiors of lunar spacecraft, the permanently shadowed south polar region of the Moon, or below the surface cannot be ruled out. Analysis of selected components returned from the unmanned Surveyor III probe, including the television camera that spent over 2 years on the lunar surface found viable Streptococcus mitis bacteria from a single sample of foam collected inside the camera housing (Mitchell and Ellis 1972). Because all of the other camera components did not contain bacteria (Knittel et al. 1971), and it has been suggested that contamination of the foam occurred during analysis in the Lunar Receiving Laboratory (Rummel 2004, and in prep) that detection may not itself be compelling, but the parameters faced by the Surveyor III camera were not that extreme, from a microbial perspective, as the interior of the camera never reached temperatures higher than 70°C (Mitchell and Ellis 1971). Future microbiological investigations of the Apollo site materials that have been exposed to the lunar environment for over 30 years might provide a more important perspective than that raised by the Surveyor III issue.

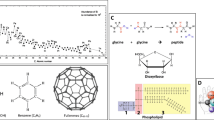

It also should be emphasized that even if bacteria delivered by lunar spacecraft are inactivated or sterilized on the Moon due to the harsh surface conditions, organic compounds from dead cells will remain and could leave a terrestrial fingerprint in lunar samples returned to Earth. A typical terrestrial microorganism such as an E. coli cell has a dry weight of 10−13 grams and is comprised of protein amino acids (57%), nucleic acids (24%), lipids (9%) and other material (Niedhardt et al. 1990). Therefore, in addition to dry heat sterilization needed to kill most bacterial cells on spacecraft surfaces, cleaning with a variety of organic solvents and degassing is required to minimize the organic load of the spacecraft and sample collection hardware. Most Apollo spacecraft hardware surfaces were cleaned to organic contamination levels of 10–100 ng/cm2, and the lunar soil sampling equipment and storage boxes were precision cleaned at the White Sands Test Facility in New Mexico to a level of 1 ng/cm2 for polished planar surfaces (Johnston et al. 1975). Estimates of the total organic contamination to lunar samples from the Apollo 11 and 12 missions based on spacecraft cleanliness was in the 0.1–100 part per billion (ppb) range (Flory and Simoneit, 1972). The microbial bioburden of the exterior and interior surfaces of the Apollo 6 command and service modules varied between ~10 and 3 × 104 microorganisms per square foot (Puleo et al. 1970). Based on the Apollo spacecraft bioburden and the survival of terrestrial microorganisms on the lunar surface, it was estimated that only 10−4–10−5 viable microorganisms per square meter of lunar surface were present at the time the Apollo samples were collected (Dillon et al. 1973). Apollo soil samples returned to the Earth were immediately analyzed for bacterial and organic contaminants in the Lunar Receiving Laboratory. Although no viable organisms were detected in the Apollo 11 and 12 samples (Oyama et al. 1970; Holland and Simmons 1973), varying levels of organic contamination in the returned samples were reported. Burlingame et al. (1970) reported an organic contamination level of 5 ppb for some Apollo 11 samples, while others reported no organic contamination above the 1 ppb level (Mitchell et al. 1971). Porphyrine-like pigments were also found in some Apollo samples at the trace ng to pg level by Hodgson (1971). Terrestrial amino acid contaminants were also observed at concentrations of up to 70 ppb (Hare et al. 1970; Harada et al. 1971; Brinton and Bada 1996). However, since these lunar samples were not analyzed for traces of organic compounds on the surface of the Moon, it remains unclear how much if any of the amino acid contamination in the lunar soils occurred during collection.

In addition to concerns about surface organic contamination of the lunar collection tools and regolith samples themselves both during collection and after return to Earth, a variety of other potential sources of contamination during the Apollo missions were noted by Simoneit and Flory (1970) including, (1) dimethyl hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide exhaust products from the lunar descent engine and reaction control system engines; (2) lunar module outgassing; (3) astronaut spacesuit leakage and venting of life support back pack; (4) particulate material from spacesuit or other sources during EVA; and (5) venting of lunar module fuel and oxidizer tanks, cabin, and waste systems. Measurements of hydrogen and oxygen isotopes of water extracted from lunar soils revealed that the water was primarily of terrestrial origin, probably from the Apollo spacecraft and astronauts (Epstein and Taylor 1972). During Apollo 17 in situ measurements on the lunar surface by the Lunar Atmospheric Composition Experiment (LACE) provided evidence for traces of methane, ammonia, and carbon dioxide in the lunar atmosphere (Hoffman and Hodges 1975). Although these volatiles may be indigenous to the Moon resulting from chemical reactions between solar implanted ions or exchange with the lunar polar cold traps, contamination by the Apollo spacecraft or the astronauts themselves cannot be ruled out as a possible source. At present it is not known whether or not past human or spacecraft contamination of the Moon is detectable in localized regions, or limited to the Apollo landing sites, themselves. It is possible that volatile contaminants from Apollo may have migrated to permanently shaded regions at the lunar poles (Butler 1997). In addition, electrostatic charging of the lunar surface and dust along the terminator could provide another mechanism for lifting and transporting contaminants across the lunar surface (Stubbs et al. 2006). Future in situ evolved gas measurements of the lunar regolith (ten Kate et al. 2010) at previous Apollo landing sites as well as “pristine” polar sites are needed to help constrain the origin of lunar volatiles and to understand the extent and persistence of volatile contamination during Apollo.

Although the lunar surface environment may represent a worst-case scenario for the survival of microorganisms and even terrestrial organic matter, lunar exploration provides a unique opportunity to use the Moon as a test-bed for future Mars exploration, where the search for evidence of life has become a primary objective. NASA is planning a series of robotic orbiters and landers to the Moon, Mars, and small bodies such as asteroids to prepare for future manned missions to these destinations (Obama 2010). ESA, as part of its Aurora exploration program, is also planning a similar set of robotic precursor missions in a similar timeframe. For these missions, in situ measurements that target key organic biomarkers and other volatiles in lunar soil samples as well as on spacecraft surfaces could be carried out using highly sensitive instruments on landers and rovers. These “ground truth” experiments on the Moon also would be particularly useful for assessing the degree of organic contamination in lunar soil samples prior to their return to Earth, as well as the stability of organic compounds in sun-exposed and shadowed regions on the surface of the Moon. Furthermore, in situ experiments carried out at previous lunar landing sites such as Apollo could provide important information regarding the extent that previous activities associated with the Apollo missions contaminated the Moon during lunar surface operations.

The use of sensitive robotic experiments to detect contamination that may still be present nearly 40 years after humans first explored the surface of the Moon may be critical to help establish a contamination baseline, but there are broader contamination challenges regarding a more sustained human presence on both the Moon and Mars. Such considerations should be kept in mind as we prepare for sustained human exploration (McKay and Davis 1989; Lupisella 1999). Human exploration could, in fact, confound the search for life on Mars, since the presence of humans will dramatically increase the amount of terrestrial organic material, potentially making the detection of indigenous organic matter exceedingly difficult, if not impossible. Future robotic and human missions to the Moon could provide a unique opportunity to carry out ground-truth experiments using in situ life detection instruments to help understand the extent of forward contamination by robotic spacecraft and human missions over well understood activities and time associated with previous lunar missions—an opportunity that may be lost if not implemented before future human missions. Ultimately, these experiments will help guide future planetary protection requirements and implementation procedures for robotic and human missions to Mars.

References

K.L.F. Brinton, J.L. Bada, A reexamination of amino acids in lunar soils: implications for the survival of exogenous organic material during impact delivery. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 60, 349–354 (1996)

M.J. Burchell, R. Robin-Williams, B.H. Foing, The SMART-1 lunar impact. Icarus 207, 28–38 (2010)

A.L. Burlingame, M. Calvin, J. Han, W. Henderson, W. Reid, B.R. Simoneit, Lunar organic compounds: search and characterization. Science 167, 751–752 (1970)

B.J. Butler, The migration of volatiles on the surfaces of Mercury and the Moon. J. Geophys. Res. 102, 19283–19291 (1997)

COSPAR, Planetary Protection Policy (revised 20 July 2008), COSPAR, Paris, France, http://cosparhq.cnes.fr/Scistr/PPPolicy(20-July-08).pdf (2008)

D.L. DeVincenzi, P.D. Stabekis, J.B. Barengoltz, A proposed new policy for planetary protection. Adv. Space Res. 3, 13 (1983)

R.T. Dillon, W.R. Gavin, A.L. Roark, C.A. Trauth Jr, Estimating the number of terrestrial organisms on the Moon. Space Life Sci. 4, 180–199 (1973)

S. Epstein, H.P. Taylor Jr, O18/O16, Si30/Si28, C13/C12, and D/H studies of Apollo 14 and 15 samples, in Proceeding 3rd Lunar Science Conference (1972), pp. 1429–1454

D.A. Flory, B.R. Simoneit, Terrestrial contamination in Apollo lunar samples. Space Life Sci. 3, 457–468 (1972)

K. Harada, P.E. Hare, C.R. Windsor, S.W. Fox, Evidence for compounds hydrolyzable to amino acids in aqueous extracts of Apollo 11 and Apollo 12 lunar fines. Science 173, 433–435 (1971)

P. E. Hare, K. Harada, S.W. Fox, Analyses for amino acids in lunar fines, in Proceedings Apollo 11 Lunar Science Conference, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta Suppl. 1, vol. 2 (1970), pp. 1799–1803

B. Harvey, Soviet and Russian Lunar Exploration (Springer/Praxis Publishing Ltd, Chichester, UK, 2007), p. 317

G.H. Heiken, D.T. Vaniman, B.M. French, Lunar Sourcebook: A User’s Guide to the Moon (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1991), p. 756

G.W. Hodgson, E. Bunnenberg, B. Halpern, E. Peterson, K.A. Kvenvolden, K. A, C. Ponnamperuma, Lunar pigments: Porphyrin-like compounds from an Apollo 12 sample, in Proceeding 2nd Lunar Science Conference, vol. 2 (Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston, TX, 1971), pp. 1865–1874

J.H. Hoffman, R.R. Hodges, Molecular gas species in the lunar atmosphere. Moon 14, 159–167 (1975)

J.M. Holland, R.C. Simmons, The mammalian response to lunar particulates. Space Life Sci. 4, 97–109 (1973)

G. Horneck, H. Bücker, G. Reitz, Long-term survival of bacterial spores in space. Adv. Space Res. 14, 41–45 (1994)

R.S. Johnston, J.A. Mason, B.C. Wooley, G.W. McCollum, B.J. Mieszkuc, The lunar quarantine program, in Biomedical Results of Apollo, ch. 1, NASA SP-368, (1975), pp. 407–424

M.D. Knittel, M.S. Favero, R.H. Green, Microbiological sampling of returned Surveyor III electrical cabling, in Proceeding 2nd Lunar Science Conference, vol. 2 (Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston, TX, 1971), pp. 2715–2719

M. Lupisella, Ensuring the scientific integrity of possible Martian life, paper IAA-99-IAA.13.1.08 presented at the International Astronautical Federation Congress, American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Amsterdam (1999)

C.P. McKay, W. Davis, Planetary protection issues in advance of human exploration of Mars. Adv. Space Res. 9, 197–202 (1989)

J.M. Mitchell, T.J. Jackson, R.P. Newlin, W.G. Meinschein, E. Cordes, V.J. Shiner, Jr, Search for alkanes containing 15 to 30 carbon atoms per molecule in Apollo 12 lunar fines, in Proceeding 2nd Lunar Science Conference, vol. 2 (Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston, TX, 1971), pp. 1927–1928

F.J. Mitchell, W.L. Ellis, Surveyor III: Bacterium isolated from lunar-retrieved TV camera, in Proceeding 2nd Lunar Science Conference, vol. 3 (Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston, TX, 1971), pp. 2721–2733

F.J. Mitchell, W.L. Ellis, Microbe survival analyses, part A, Surveyor 3: bacterium isolated from lunar retrieved television camera. In Analysis of Surveyor 3 Material and Potographs Returned by Apollo 12, (NASA 1972), pp. 239–248

F.C. Niedhardt, J.L. Ingraham, M. Schaechter, Physiology of the Bacterial Cell: A Molecular Approach (Sinauer Associates, Inc, Sunderland, 1990), p. 506

B.H. Obama, National Space Policy of the United States of America, June 28, 2010 (2010)

R.W. Orloff, Apollo by the Numbers (NASA History Division, Washington, DC, 2000)

V.I. Oyama, E.L. Merek, M.P. Silverman, A search for viable organisms in a lunar sample. Science 167, 773–775 (1970)

J.R. Puleo, N.D. Fields, B. Moore, R.C. Graves, Microbial contamination associated with the Apollo 6 spacecraft during final assembly and testing. Space Life Sci. 2, 48–56 (1970)

J.D. Rummel, P.D. Stabekis, D.L. DeVincenzi, J.B. Barengoltz, COSPAR’s planetary protection policy: a consolidated draft. Adv. Space Res. 30, 1567–1571 (2002)

J.D. Rummel, Strep, Lies, and 16 mm Film: did S. mitis survive on the Moon? Should humans be allowed on Mars? Abstract for 2004 Astrobiology Science Conference, Moffett Field, CA, Cambridge University Press, Int. J. Astrobiol., Supplement, 7–8 (2004)

C. Sagan, Biological contamination of the Moon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 46, 396–401 (1960)

A.A. Siddiqi, Deep space chronicle: a chronology of deep space and planetary probes, 1958–2000. Mongraphs in Aerospace History, 24. NASA, Office of External Relations, NASA History Office, Washington, DC, NASA SP-2002-4524 (2002)

B. Simoneit, D. Flory, Apollo 11, 12, and 13 Organic Contamination Monitoring History, UC Berkeley Report to NASA (1970)

T.J. Stubbs, R.R. Vondrak, W.M. Farrell, A dynamic fountain model for lunar dust. Adv. Space Res. 37, 59–66 (2006)

I.L. Ten Kate, E.H. Cardiff, J.P. Dworkin, S.H. Feng, V. Holmes, C. Malespin, J.G. Stern, T.D. Swindle, D.P. Glavin, VAPoR—Volatile analysis by pyrolysis of regolith-an instrument for in situ detection of water, noble gases, and organics on the Moon, Planet. Space Sci. 58, 1007–1017 (2010)

K. Uesugi, Results of the MUSES-A “Hiten” mission. Adv. Space Res. 18, 69–72 (1996)

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the helpful comments of Ian Crawford, Everett Gibson, and one anonymous reviewer. We are grateful for support from the NASA Astrobiology Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Glavin, D.P., Dworkin, J.P., Lupisella, M. et al. In Situ Biological Contamination Studies of the Moon: Implications for Planetary Protection and Life Detection Missions. Earth Moon Planets 107, 87–93 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11038-010-9361-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11038-010-9361-4