Abstract

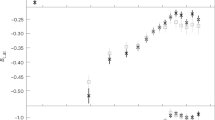

TOGETHER with E. M. Burbidge and C. R. Lynds, we have recently given a table of more than forty quasistellar objects which includes red-shifts, optical magnitudes, and line spectrum data1. Radio fluxes are available for nearly all these objects. Provided we restrict ourselves to objects with flux values > 8 × 10−26 W m−2 (c/s)−1 at 178 Mc/s, the list is sufficiently complete (over the portion of the sky available to Palomar, Lick and Kitt Peak, the observatories from which the red-shift measurements have been made) for approximate number counts to be made. There are thirty such objects. It happens that 30=2 + 22 + 23 + 24, which provides the following simple way of making a number count. Write N(S) for the number of objects with flux density ≥S and define S1, S2, S3, S4 to be the smallest values of S such that N(S1) = 2, N(S2) = 2 + 22, N(S3) = 2 + 22 + 23, N(S4) = 30. This permits four points to be plotted in the log N–log S plane. These points are shown in Fig. 1. Joining them gives a slope close to –1.5, not quite as steep as the value of –1.85 obtained from the counting of all radio sources, and not as steep as the value of about –2.2 obtained by Véron2 for all quasi-stellar objects contributing to the 3C catalogue. However, the slope of the points in Fig. 1 is evidently influenced by the two lower points which must be subject to a considerable statistical scatter. So no undue significance should be attached to the particular value of the sJope which these points happen to give. What does appear to be significant, however, is that even this small sample of quasi-stellar objects shows the usual relation between N and S, NS3/2 approximately constant. The result NS3/2 approximately constant has always been interpreted in terms of distances and volumes–for example, for a Euclidean universe and for objects all with the same intrinsic emission, N ∝ r3, S ∝ r−2 (r being the distance). A similar interpretation for our sample of quasi-stellar objects requires the objects with smaller S to be at the greater distance, in any event statistically. Objects with S≍S4 should be statistically farther away than objects with S≍S3, and so on. If we make the assumption that the red-shifts z of the quasi-stellar spectra arise from the cos-mological expansion of the universe, then small S must be correlated with large z. In Fig. 2 it is shown emphatically that this is not so. Thus if we adopt the usual distance-volume interpretation of the result NS3/2 constant, we must conclude that the red-shifts have nothing to do with distances.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Burbidge, G. R., Burbidge, M., Hoyle, F., and Lynds, C. R., Nature, 210, 774 (1966).

Véron, P., paper presented at Intern. Astro. Union Symposium in Erevan, U.S.S.R., May 1966, on “Instability Phenomena in Galaxies”; Ann. d'Astro. (in the press).

Sandage, A. R., Astrophys. J., 141, 1560 (Fig.4) (1965).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

HOYLE, F., BURBIDGE, G. Relation between the Red-shifts of Quasistellar Objects and their Radio and Optical Magnitudes. Nature 210, 1346–1347 (1966). https://doi.org/10.1038/2101346a0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/2101346a0

This article is cited by

-

A parallax distance to 3C 273 through spectroastrometry and reverberation mapping

Nature Astronomy (2020)

-

The Hubble relation for a comprehensive sample of QSOs

Journal of Astrophysics and Astronomy (2003)

-

Anomalous redshifts and the variable mass hypothesis

Astrophysics and Space Science (1996)

-

Redshift and radio magnitude of quasars

Astrophysics and Space Science (1978)

-

Was there really a Big Bang ?

Nature (1971)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.