Abstract

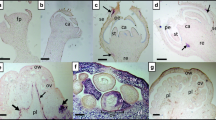

Nine accessions of three cucurbit species, ten of eight legume species, three of lettuce (Lactuca sativa) and 34 of 14 Solanaceae species were inoculated with a Dutch isolate of the tomato powdery mildew fungus (Oidium lycopersici) to determine its host range. Macroscopically, no fungal growth was visible on sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum), lettuce, petunia (Petunia spp.) and most legume species (Lupinus albus, L. luteus, L. mutabilis, Phaseolus vulgaris, Vicia faba, Vigna radiata, V. unguiculata). Trace infection was occasionally observed on melon (Cucumis melo), cucumber (Cucumis sativus), courgette (Cucurbita pepo), pea (Pisum sativum) and Solanum dulcamara. Eggplant (Solanum melongena), the cultivated potato (Solanum tuberosum) and three wild potato species (Solanum albicans, S. acaule and S. mochiquense) were more heavily infected in comparison with melon, cucumber, courgette, pea and S. dulcamara, but the fungus could not be maintained on these hosts. All seven tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) accessions were as susceptible to O. lycopersici as tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum cv Moneymaker), suggesting that tobacco is an alternative host. This host range of the tomato powdery mildew differs from that reported in some other countries, which also varied among each other, suggesting that the causal agent of tomato powdery mildew in the Netherlands differ from that in those countries. Histological observations on 36 accessions showed that the defense to O. lycopersici was associated with a posthaustorial hypersensitive response.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abiko K (1978) Studies on the specialization of parasitism of Sphaerotheca fuliginea (Schlecht.) Pollacci. I. Powdery mildew fungi parasitic on cucurbits, eggplant, edible burdock and Japanese butterbur. Annals Phytopathol Soc Japan 44(5): 612–618

Abiko K (1982) Studies on the specialization of parasitism of Sphaerotheca fuliginea (Schlecht) Pollacci. III. Powdery mildew fungi parasitic on weeds. Bulletin of the Vegetable and Ornamental Crops Research Station, Series A 10: 63–67

Abiko K (1983) Studies on the specialization of parasitism in Erysiphe cichoracearum. Bulletin of the Vegetable and Ornamental Crops Research Station, Series A 11: 119–126

Amano K (1986) Host range and geographical distribution of the powdery mildew fungi. Japan Scientific Society Press, Tokyo, Japan (in data base provided by S. Takamatsu)

Angelov D, Georgiev P and Stamova L (1993) Identification of the new powdery mildew agent on tomatoes in Bulgaria. Proceedings of the XIIth Eucarpia Meeting on Tomato Genetics and Breeding, Plovdiv, Bulgaria, 27–31 July (pp 51–54)

Arredondo CR, Davis RM, Rizzo DM and Stahmer R (1996) First report of powdery mildew of tomato in California caused by an Oidium sp. Plant Dis 80: 1303

Baum BR and Savile DBO (1985) Rusts (Uredinales) of Triticeae: evolution and extent of coevolution, a cladistic analysis. Bot J Linnean Soc 91: 367–394

Blumer S (1967) Echte Mehltaupilze (Erysiphaceae), (pp 206–207) Veb Gustav Fischer Verlag Jena, Jena, Germany

Braun U (1987) A Monograph of the Erysiphales (powdery mildews). Nova Hedwigia Beihefte H89

Cirulli M (1976) Powdery mildew of pea and behaviour of susceptible and resistant varieties towards Erysiphe polygoni DC. Informatore Fitopatologico 26: 11–15

Cook RTA, Inman AJ and Billings C (1997) Identification and classification of powdery mildew anamorphs using light and scanning electron microscopy and host range data. Mycol Res 101(8): 975–1002

Corbaz R (1993) Spread of a powdery mildew of the Cucurbitaceae (Erysiphe cichoracearum) to tomatoes. Revue Suisse de Viticulture, d'Arboriculture et d'Horticulture 25: 389–391

Elmhirst JF and Heath MC (1989) Interactions of the bean rust and cowpea rust fungi with species of the Phaseolus-Vigna plant complex. II. Histological responses to infection in heat-treated and untreated leaves. Can J Bot 67: 58–72

Fletcher JT, Smewin BJ and Cook RTA (1988) Tomato powdery mildew. Plant Pathol 37: 594–598

Holst-Jensen A, Kohn LM, Jakobsen KS and Schumacher T (1997) Molecular phylogeny and evolution of Monilinia (Sclerotiniaceae) based on coding and noncoding rDNA sequences. American J Bot 84: 686–701

Huang CC, Groot T, Meijer-Dekens F, Niks RE and Lindhout P (1998) The resistance to powdery mildew (Oidium lycopersicum) inLycopersicon species is mainly associated with hypersensitive response. Eur J Plant Pathol 104: 399–407

Ignatova SI, Gorshkova NS and Tereshonkova (1997) Powdery mildew of tomato and sources of resistance. (Appendix to) Proceedings of the XIII Meeting of the EUCARPIA Tomato Working Group, 19–23 January, Jerusalem, Israel

Johnson LEB, Bushnell WR and Zeyen RJ (1982) Defense patterns in nonhost higher plant species against two powdery mildew fungi. I. Monocotyledonous species. Can J Bot 60: 1068–1083

Kiss L (1996) Occurrence of a new powdery mildew fungus (Erysiphe sp.) on tomato in Hungary. Plant Dis 80: 224

Lindhout P, Pet G and Van der Beek JG (1994) Screening wild Lycopersicon species for resistance to powdery mildew (Oidium lycopersicum). Euphytica 72: 43–49

Mieslerov´a B and Lebeda A (1999) Taxonomy, distribution and biology of the tomato powdery mildew (Oidium lycopersici). J Plant Dis Protect 106: 140–157

Noordeloos ME and Loerakker WM (1989) Studies in plant pathogenic fungi-II: on some powdery mildews (Erysiphales) recently recorded from the Netherlands. Persoonia 14: 51–60

Palti J (1988) The Leveillula mildews. Bot Rev 54: 423–535

Reddy TSN, Nagarajan K and Chandwani GH (1979) Studies on powdery mildew disease on tobacco. Tobacco Res 5: 76–82

Savile DBO (1971) Coevolution of the rust fungi and their hosts. Quarterly Rev Bio 46: 211–218

Singh UP and Singh HB (1983) Development of Erysiphe pisi on susceptible and resistant cultivars of pea. Transact Brit Mycol Soc 81: 275–278

Smith VL, Douglas SM and Lamondia JA (1997) First report of powdery mildew of tomato caused by an Erysiphe spp. in Connecticut. Plant Dis 81: 229

Staub T, Dahmen H and Schwinn FJ (1974) Light-and scanning electron microscopy of cucumber and barley powdery mildew on host and nonhost plants. Phytopathology 64: 364–372

Storer AJ, Gordon TR, Dallara PL and Wood DL (1994) Pitch canker kills pines, spreads to new species and regions. California Agric 48: 9–13

Whipps JM and Helyer NL (1994) Occurrence of powdery mildew on aubergine in West Sussex. Plant Pathol 43: 230–233

Whipps JM, Budge SP and Fenlon JS (1998) Characteristics and host range of tomato powdery mildew. Plant Pathol 47: 36–48

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, CC., Biesheuvel, J., Lindhout, P. et al. Host Range of Oidium lycopersici Occurring in the Netherlands. European Journal of Plant Pathology 106, 465–473 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008706614291

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008706614291